Ruth Bader Ginsberg: Her Life, Legacy, and Seat

“Each time a woman stands up for herself, without knowing it possibly, without claiming it, she stands up for all women.” -Maya Angelou

September 21, 2020

On Friday night, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg died. In many ways, it seemed impossible. I mean this not because of her famous planks and workouts, but because in her lifetime, she grew to be larger than life; an enduring symbol for feminism, spectacular intellect, and justice. She lived in many’s consciousnesses as a real-life superhero — the Notorious RBG.

Ginsberg was born in Brooklyn. Her family, particularly her mother, Celia, was passionate about education. Ginsberg excelled in school, graduating high school at 15. Her mother, a star student herself, did not continue her education past high school, and instead financially supported her brother’s college aspirations. Celia Bader passed away the day before her daughter’s high school graduation. When she was nominated for the Supreme Court in 1993, Ginsberg spoke of her mother, saying “I pray that I may be all that she would have been had she lived in an age when women could aspire and achieve and daughters are cherished as much as sons.”

Ginsberg went on to attend Cornell University, earning a Bachelor of Arts degree for Art History. She graduated Cornell at top of her class. During her time there, she met her husband, Martin Ginsberg. He would eventually become a tax lawyer, at a time considered “the best in New York.” She often remarked, “He was the first boy I ever knew who cared that I had a brain.” During their time at Harvard together, Martin would apparently brag to “anyone who would listen that his fiancée would make Law Review (an honor reserved exclusively for those at the very top of the class)”. They were married soon after graduation.

Their marriage, an equal partnership, not just in aspirations but also in domestic work, was remarkably modern. So modern in fact, that when the RBG biopic “On the Basis of Sex” was being financed, “Backers offered to fund the film if [Martin] was rewritten as angrier, or less understanding; maybe he should threaten to divorce his wife if she didn’t drop the case,” said Daniel Stiepleman, the film’s writer and Ginsberg’s nephew.

When Martin was called to military service in Oklahoma, Ginsberg worked for the Social Security Administration. She was up for a major promotion at work, but once she reported that she was pregnant, she lost her promotion, even being demoted.

The following year, she enrolled in Harvard Law, one of nine women in a 550 person class. The Dean of Harvard Law famously asked every female law student “Why are you at Harvard Law School, taking the place of a man?” Her witty response: “I’m at Harvard to learn more about [my husband’s work]. So I can be a more patient and understanding wife.”

Ginsberg then transferred to Columbia University for her husband’s work. She earned her law degree and graduated top of her class at Columbia, writing for the Columbia Law Review. She was also the first female member of the Harvard Law Review. When her husband had testicular cancer, she transcribed his notes for him, while being a new mother, while still at the top of her class.

Her formidable intellect is well known and well documented. However, she struggled to find work after graduating, she recounted the difficulty of finding a job years later, recalling one legal office that said they had hired a woman the previous year and didn’t need another. Eventually, she went on to clerk for U.S. District Judge Edmund L. Palmieri became a professor at Rutgers Law School and Columbia Law School where she was the first female professor to earn tenure at Columbia.

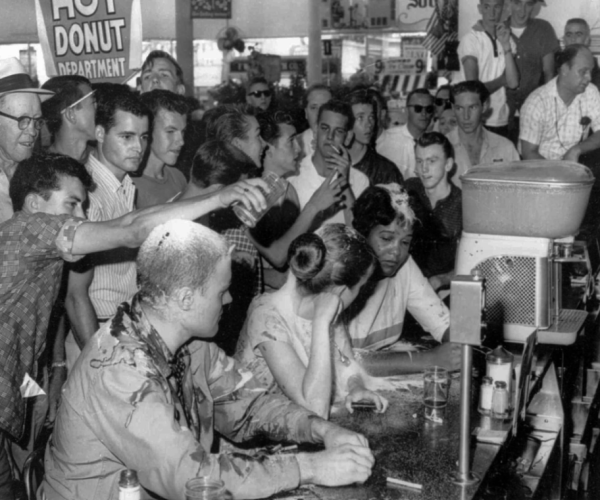

She also directed the Women’s Rights Project of the American Civil Liberties Union during the 1970s, the height of the Women’s Liberation Movement. She argued six landmark Supreme Court Cases, winning five, arguing that gender-based discrimination, including traditional gender roles, harms both men and women. She was strategic, pointing out specific statutes and sections, which allowed for incremental reform, ultimately culminating in sweeping reform.

Interestingly, many feminists criticized her for representing men in her gender-discrimination cases. Some even argued that it was anti-feminist. Looking back, the decision was brilliant because it forced men to see how gender-discrimination might negatively affect their own lives, eventually even women’s lives, fundamentally challenging the notion that these laws supposedly benefited women. Many at the time thought that gender-based laws protected women or absolved them from difficult responsibilities, allowing for a more demure and feminine lifestyle.

Ginsberg argued Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, which was fundamentally about a father not receiving special benefits afforded to women when their husband died to help them care for small children. The Social Security Act of 1935 essentially codified the notion that raising children was women’s work, a legal distinction between men’s work and women’s work in society. The assumption was that this law would help women, while Ginsberg argued “The laws of this policy help to keep women not on a pedestal, but in a cage.”

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia where she served until 1993 when President Clinton appointed her to the Supreme Court. She was the second woman ever to serve on the Supreme Court, after Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. Linda Greenhouse, a former Supreme Court correspondent for the New York Times said “She had a really radical project: to erase the functional difference between men and women in society.”

Ginsberg’s notoriety came late in her life. For a while after Justice O’Connor’s retirement, Ginsberg was the only female Justice on the bench. Public admiration for the Justice consistently grew, exploding after the documentary about her life “RBG”, which cemented her as an iconic figure in popular culture. Her formidable mind, “dissent collar”, and feminist ideology launched her into stardom, a hero to young girls and boys, legal students, and everyday people. On SNL, Kate McKinnon often portrayed the Justice in rap songs, tossing out “Gins-burns” left and right, highlighting the Justice’s spunk and tenacity. On Halloween, between superheroes and ghosts, you could often find small children donning her iconic collar. At marches, her quotes would galvanize crowds.

She seemed too big to die. Too emblematic of stability, integrity, and justice. Too integral to our political process. Amidst political turbulence, she was a port in the storm. A reliable voice for sanity and equality. She was many people’s, myself included, canary in the coal mine. With her on the bench, we would be safe. So much seems uncertain now.

Prior to Justice Ginsberg’s death, President Trump floated possible candidates for a new Supreme Court Justice, candidates that included Senators Ted Cruz and Tom Cotton. In response, Senator Cotton tweeted out “It’s time for Roe. v. Wade to go.”

Ginsberg was particularly vocal about Roe v. Wade and women’s right to choose: “The decision whether or not to bear a child is central to a woman’s life, to her well-being and dignity. It is a decision she must make for herself. When the government controls that decision for her, she is being treated as less than a full adult human responsible for her own choices.” Last year, numerous states attempted to pass legislation that would limit and restrict a woman’s right to an abortion. Many worry that a conservative bench could overturn Roe. v. Wade, effectively stopping women from a safe and legal abortion.

President Trump has appointed two Supreme Court candidates during his time in office. Both of which, Justice Neil Gorsuch and Justice Brett Kavanaugh, took seats from Conservative incumbents. If another conservative justice is appointed and confirmed, the Court would have an even stronger Conservative lean, with three liberal justices, five conservative justices, and Chief Justice Roberts as a swing with conservative tendencies. And based on the relatively young ages of Trump’s appointees, this could affect the Court for decades.

Almost as a concession, Trump recently announced that his appointee would be a woman. But with 43 days until the election, and early voting already begun in some states, the battle over appointment will be vicious.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said in 2016, following the death of Justice Antonin Scalia eight months before the election, “Given that we are in the midst of the election process, we believe that the American people should seize the opportunity to weigh in on whom they trust to nominate the next person for a lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court.” After President Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland, he added: ‘The American people may well elect a president who decides to nominate Judge Garland for Senate consideration. The next president may also nominate someone very different. Either way, our view is this: Give the people a voice.”

And in response to a possible lame duck session confirmation, the time between the election’s results and the inauguration of a new president, he added: “We think the important principal in the middle of this presidential year is that the American people need to make this decision. Not this lame duck president on the way out the door, but the next president.”

Apparently eight months was too close to the election, while 43 days is plenty of time. Senator McConnell has stated his intent to confirm any Supreme Court appointee.

Senator Lisa Murkowski, a Republican Senator from Alaska, who in October about a possible Supreme Court confirmation said “I think that’s too close, I really do.” She expanded on her statement yesterday “For weeks, I have stated that I would not support taking up a potential Supreme Court vacancy this close to the election,” Ms. Murkowski said in a statement. “Sadly, what was then a hypothetical is now our reality, but my position has not changed.” She is among a growing number of Republican senators who have publicly stated that they will not support a Supreme Court confirmation before the election.

Much has been made of Ginsberg’s last wish: “My most fervent wish is that I not be replaced until a new president is installed.” How devastated she must have felt to spend her last days fearing a future she would not be a part of. How scary it is for our nation’s first thoughts to not be of her life, but her seat.

So now, presented with the possibility of a nomination and confirmation, we will mourn our loss, celebrate her life, and fight like hell to protect her legacy and seat.