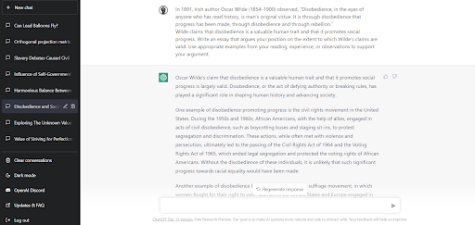

Watched

October 27, 2016

Terrorism has become an international epidemic. Domestically, the US has endured the fifteenth anniversary of September 11th, shootings in San Bernardino and Orlando, and bombings in New York and New Jersey, all in the past year. These threats percolate in the psyche of the American consciousness and have driven a wave of sentiment for national security. But at what cost? The next question that has arisen is: what is the best way to counter terrorism, without infringing upon privacy rights?

After September 11th, the United States government created provisions to counteract terrorism. One measure included refocusing the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) towards improving counter terrorism. The Patriot Act, signed by President Bush six weeks after the attack on 9/11, gave the Justice department new powers in intelligence-gathering. This Act also gave increased authority to the government to intercept communications involving terrorism-related crimes. This allowed investigators to aggressively track suspected terrorists on the internet and provided new subpoena powers to obtain financial information. The Act also reduced bureaucracy by allowing investigators to use a single court order for tracking national communication, encouraging the sharing of information between local law enforcement and the Intelligence Community.

The Patriot Act sparked a new controversy as to how much information the government should have access to, and when safety concerns should trump privacy rights. In February 2016, the US government sued Apple, demanding that the tech company create software that would weaken iPhone security settings, in order to aid government investigators. This came on the heels of a failed attempt by said investigators, to retrieve data from Syed Farook’s phone, the San Bernardino gunman. Apple fought back, insisting that the request for a “backdoor” represented a violation to citizens’ privacy. This controversy has brought up concerns for the American public, as to how insecure our personal information has become.

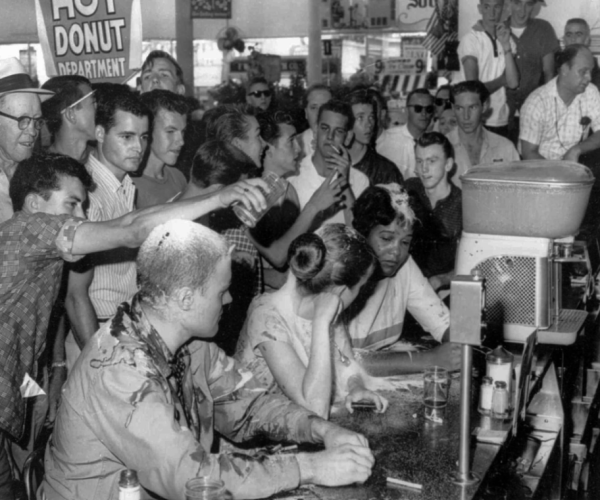

In the recent New York and New Jersey bombings, the police used the emergency alert system to issue a cellphone message to millions of people in the area, telling them to watch out for Ahman Khan Rahami, who was described as “armed and dangerous”. Surveillance cameras were able to capture images of Rahami both placing the bomb and leaving the scenes of the explosion in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood, and another site four blocks away (where he left a similar device that failed to explode, which was taken into custody by the police and analyzed). Authorities were able to match Rahami’s face to a U.S. immigration photo database. Automated facial recognition technology is becoming increasingly common, as police departments and airports are using this technology to digitally search records of people and subsequently identify them. The Fourth Amendment protects the right of people against unreasonable searches and seizures, unless there is probable cause. To what extent does governmental access to surveillance cameras, personal information, and tracking technology, violate an individual’s privacy rights?

Governmental access to technology is able to protect the public interest, but to what extent does this use of technology infringe upon an individual’s civil liberties? When an individual appears suspicious of a crime, there is the potential to gain more evidence from surveillance cameras and personal electronics. An individual may not be guilty, and by American law, is supposed to be considered innocent until proven otherwise. With the invasion of personal emails and mobile phones, for instance, there might be more conflicting evidence that cannot be proven irrelevant or conversations that could be taken out of context. People could unwittingly incriminate themselves, because they do not understand the extent to which they are being watched. This is why it is essential that checks and balances remain in place to ensure that there is a just system.

As George Orwell forewarned, “something like 1984 could actually happen. This is the direction the world is going in at the present time. In our world, there will be no emotions except fear, rage, triumph, and self-abasement…If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face, forever. The moral to be drawn from this dangerous nightmare situation is a simple one: don’t let it happen. It depends on you.” Citizens should not be living in fear of their governments, but rather, should be able to feel their government is a necessary power that protects its citizens. Making sure the monitors have finite power is critical, if individuals are to be able to act, think, and speak freely, without fear and threat of governmental oppression.

In contrast to the government at large, schools have completely different policies on privacy, and rules are created with the students’ safety prioritized above all else. In the Radnor Township School District, students have grown up under surveillance, from cameras in the hallways, on their buses, and on their school-issued ipads. Administrators are constantly reminding students that they are being watched.

In fifth grade, I remember my bus number being called to the auditorium, where the administration explained to us that we were demonstrating inappropriate behavior. They reminded us that they have cameras on the bus that see everything we do, in an attempt to control our behavior. They believed that if we knew we were being watched, we would behave better. They were right; it was an effective method of control. Unfortunately, those on our bus quickly slipped back into old ways. I remember in seventh grade, an administrator riding on the bus with us, after hearing several complaints and watching the videotapes of our inappropriate behavior. Again, we were reminded that all RTSD buses have cameras, and I remember the fear that all of us had, regardless of our complicity or actual guilt.

This monitoring technique is also used on school property, to diminish other misbehaviors, such as theft and vandalism. With surveillance, they are able to both discourage criminal activity and catch people in the act of committing crimes. While constant surveillance does invade an individual’s privacy, inside the school building it is deemed a necessary, albeit imperfect, precaution to ensure minors’ safety. Particularly near entrances in and out of the building, cameras can also diminish dangerous people from entering the building.

School cameras are not the only devices watching teenagers. Social media and smartphones have taken away individuals’ privacy, because it broadcasts their lives all over the Internet. Whether or not they post themselves, teens know that they will be featured in other people’s posts, and their actions will be digitally chronicled. Consequently, current students are used to a much lower level of privacy than previous generations of Americans.

The increase of technology has created, like everything else, an assortment of pros and cons. It has increased information sharing, and the ability to obtain more evidence, catch more criminals, and purportedly prevent more incidents. At the same time, however, this increased use of forensic technology, must be weighed against the risk of privacy infringement. A citizen’s right to privacy, without fear of others watching, must also be respected in a free society. It is a new technological conundrum we will have to learn to balance, so that we don’t turn into the Brotherhood.