Veterans Day: Hearing Voices of our Past

November 12, 2018

Annually, November 11th is Veterans Day in the United States. On this day, we honor veterans from all wars, along with current members of the armed forces, for their service to our country. At Radnor High School, we deeply value the significance of this day. The recently built Wall of Honor is just one example, not to mention the numerous activities and services students participate in throughout the year. Veterans Day marks the anniversary of another important event: the end of World War I. In other countries November 11th is observed as Armistice Day: On the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, an armistice, or temporary cessation of hostilities, was declared between the Allied nations and Germany in World War I. This year marked the 100th anniversary of that event.

The Radnor Memorial Library recently uploaded the Radnor Memorial Library Oral History Project, a series of interviews with Radnor’s senior citizens made in the 1980s, to their online audiobook collection. At the time, the senior citizens were people born in the late 1800s and early 1900s. To hear them speak about the early 20th century is a very rare opportunity, as all of these people have now passed away. Listening to these stories provides an insightful perspective on the experience of past veterans. I listened to two men who served in World War I from Radnor: John J. Wack, and Dominick Cornacchio.

Born in Mt. Pleasant, Mr. Wack moved to Wayne when he was young, and as a teenager he ended up helping the local country doctor make his house calls. The doctor bought one of the first cars in town so he could respond quickly to patients, and hired Mr. Wack to drive for him. He eventually became more involved with the doctor and assisted in minor surgeries. When the US entered World War I, he was encouraged to enlist in a Philadelphia hospital program that sent a group of doctors overseas to help the army.

After enlisting, he landed in France and became part of a casualty clearing station- “it was right behind front lines…we operated on the ones who wouldn’t live before reaching a hospital,” he said. “We were in an old lace factory in Belgium when the Armistice was signed… the Germans had walked in there a few days after war was declared and they were never driven out, not until the end of the war.” He found the factory “…filled with young German soldiers, maybe 15 years old. All of them had paper dressings, and their wounds had maggots in them.” He reported being pleased they had maggots, (to the surprise of the interviewer), later explaining maggots clean wounds of dead and infected flesh.

On Armistice day, he and another soldier wandered into the local village, and when they entered the town square, they became swamped with celebrating people. After they left the square, a loud explosion was heard. When the Germans retreated, they planted explosives in the town square, which were then detonated later remotely. They spent the next few days treating the injured before preparing to be shipped back home. Mr. Wack came back to the USA during the Easter of 1919. It was difficult for him to describe the celebration and his emotions after returning home. (He begins choking up on the tape.) “it was….was something.” Despite the horrors he saw as a doctor in war, he maintained a positive attitude afterwards. In fact, thanks to the war he ended up meeting his wife overseas as a nurse, and they married shortly after.

Dominick Cornacchio was born in Italy, and immigrated to the USA when he was a teenager in the early 1900s. He stayed with a family in Wayne from his Italian hometown for nine years. The girls of the family taught him to read and write a little English. Despite the lessons, he still barely knew English when he got drafted . Being brought to an army camp in the South he couldn’t understand the southern accent at all. Despite the hardships he has faced, he often laughs when remembering his struggles : “they teach me to be soldier, ya know, you no understand word…they put me in a field by myself and Sergeant was just like bulldog, very mean….(laughs). I was good to Sergeant.”

Soon after his training, Cornacchio crossed the Atlantic and landed in France:“I was sent straight to the front…(laughs) I didn’t see no Mademoiselles, nobody. Only see guns and shooting.” After serving for 11 months, he came back and bought a house on Highland Avenue with his new wife and family.

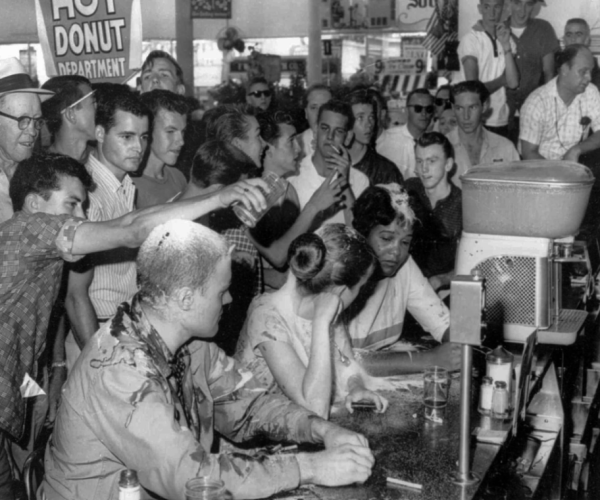

The family lived through the Great Depression in Wayne with almost no money. He was out of work for 5 years. He credits religion as the one thing that kept him going: “(Laughs) oh, God had my back at that time…even when you are starving you can still find a piece of bread.” Eventually, he became the first Italian to work at St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in Wayne. Because of racial discrimination and prejudice of that time, it was unusual for an Italian to be hired for a job normally reserved for the Irish and English. Mr. Cornacchio broke that barrier and held that job for 50 years, becoming the church gardener.

Stories like these bring the lives of our veterans from 100 years ago a little closer to our own. Remember to thank those who are serving and have served for the unimaginable sacrifices they have made for us.