Established in 1900, the College Board was founded to provide American students with access to standardized college level courses and testing to facilitate the transition between highschool and college. Today, College Board boasts its status as one of the largest test distributors in the world, generating nearly 1.1 billion dollars in revenue each year. In the United States, College Board’s SAT and AP programs have proven to be key factors in the college admissions process. With their increasingly large market share, the College Board has faced controversy related to its status as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization and its increasing monopolization of high school standardized testing. Beyond this, there have also been issues concerning the illegal sale of student data, tax payments, and vanishing AP test scores. So, let’s look deeper into this “nonprofit” and how their mission may not be as benevolent as they purport.

The College Board states as its mission that “We are a not-for-profit membership organization committed to excellence and equity in education.” While the College Board uses the terms interchangeably on their website, it’s important to note the distinction between a not-for-profit and nonprofit organization. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce states that not-for-profits are considered “recreational organizations” that should not and cannot operate with the business goal of earning profit and are typically run by volunteers. Legally, the College Board functions as a nonprofit, or 501(c)(3) organization, which allows it to generate profit as long as it reinvests it into the organization. Far from that of a volunteer, College Board CEO David Coleman’s full compensation in 2020 was 2.56 million dollars. This figure is striking even among other nonprofits. The Red Cross and Feeding America together garner nearly eight times as much revenue as College Board each year, yet the salaries of both their CEOs, combined roughly 1.7 million total, do not come close to David Coleman’s compensation.

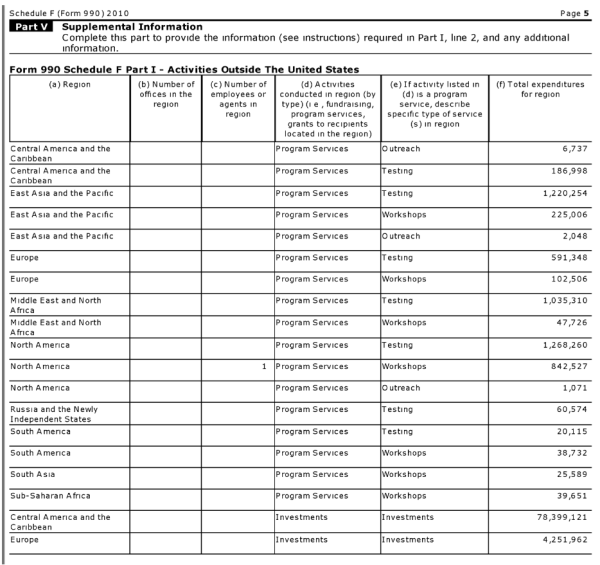

Beyond lofty financial compensation of their executives, there lies a more questionable for-profit practice hidden in the College Board’s IRS filings. Annual reports indicate revenues and expenses all across the world, which would at first make sense considering global operations. However, a closer look reveals some unexpected investments in the Caribbean larger in magnitude than the rest of their international investments.

In their Form 990 from 2010, some investments are described as partnerships and investments while others are a bit more unusual, such as “intangible drilling costs.” A footnote in an earlier tax filing reveals that these investments are in fact being sent to hedge funds in the Caribbean. A sector of College Board is dedicated solely to managing roughly a quarter billion dollars in offshore tax havens, filing separate returns every year and using tax-deductibles as a way to conceal the massive growth of the fund. This ended in 2016, when all of the offshore accounts reported multimillion dollar “charitable donations” to an unidentified recipient, all of which were tax deductible. Though not explicitly stated, College Board is the likely recipient of these donations.

Although they still retain their legal status as a nonprofit, this does not mean that College Board is exempt from monopoly law. In NCAA v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma, the Supreme court rejected the NCAA’s claim that nonprofit organizations that engage in anticompetitive practices should be impervious to antitrust laws. Justice John Paul Stevens wrote, “it is nevertheless well settled that good motives will not validate an otherwise anticompetitive practice.” Upon delivering the unanimous decision of the court, Justice Neil Gorusch highlighted the court’s regular dismissal of cases “from litigants seeking special dispensation from the Sherman Act on the ground that their restraints of trade serve uniquely important ‘social objectives’ beyond enhancing competition.” This applies to all organizations under 501(c)(3) status, regardless of their mission. The NCAA’s case has set an important precedent for nonprofits large enough to be considered bordering on a monopoly, such as the College Board.

The College Board is not protected from antitrust law, but it most definitely is protected by lobbyists. The ACT, mostly prominent in the Midwest, is one of the few competitors of the SAT and has held a large share of the standardized testing market since its founding in 1959. In 2015, College Board acquired a three year contract with the state of Michigan by offering their services for 15.4 million dollars cheaper than the ACT. At such a low price, the College Board limited potential profit, but acquired a market share that would provide a foothold for further expansion. In Colorado, until 2016 highschool juniors were required to take the ACT. However, through increased lobbying and a cut in price, College Board motivated a change in the state education policy such that all Colorado juniors are now required to take the SAT. By 2018, College Board had acquired ten state contracts, three of which were formerly held by the ACT. The College Board is actively limiting competition from ACT within their respective market, which is a red flag when determining if a firm has a monopoly or not.

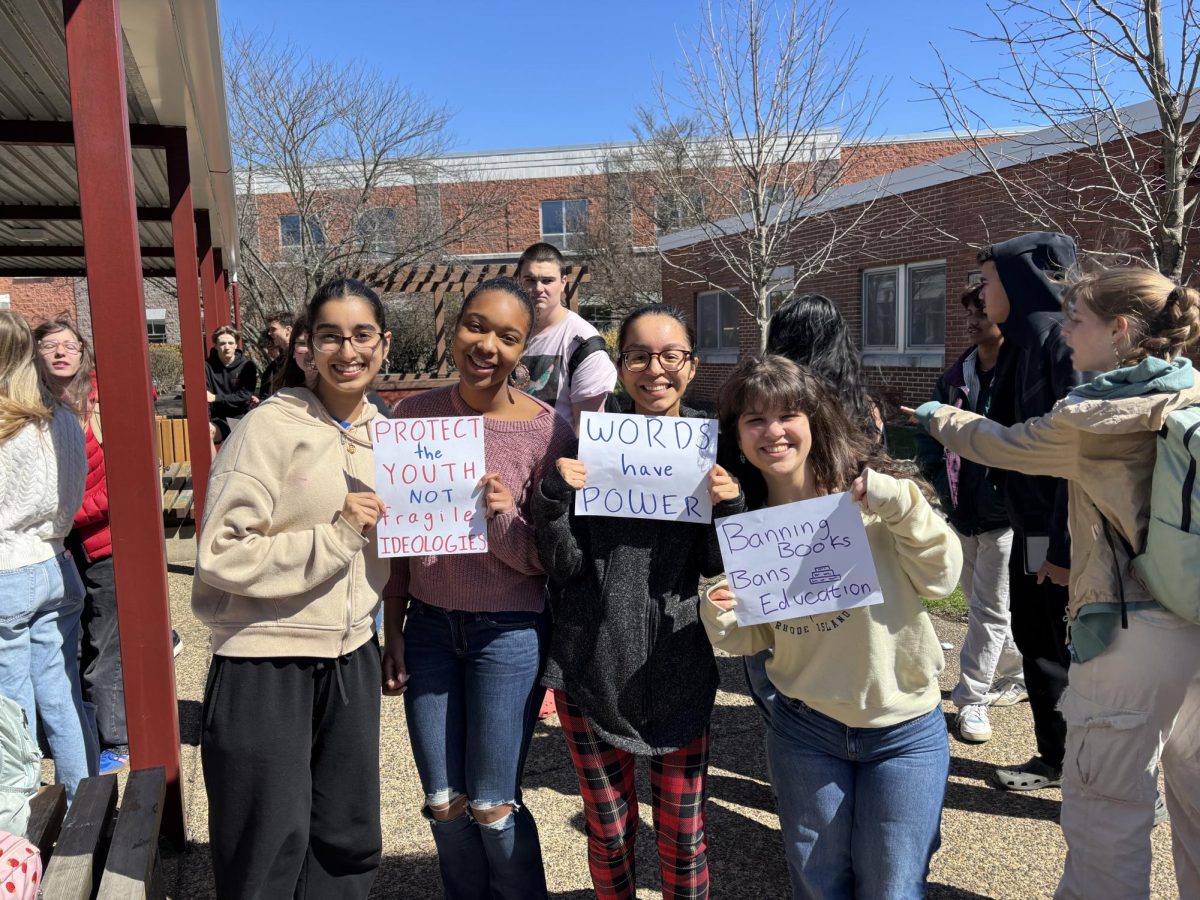

The College Board has been altering state policy with their own interests in mind for years now, but what about the students, whom they claim is their main mission to help? Unfortunately for us, the College Board’s prioritization of profit has detrimental effects on students too. In February of 2024, College Board lost a lawsuit against the state of New York and had to pay a settlement of $750,000 for the unauthorized collection and selling of students’ data to third party entities. This affected nearly 237,000 students in New York in the year 2019 alone. You may know this as their “Student Search Service,” which every AP and SAT asks you to join when you sit down. By bubbling in “yes,” you may be unknowingly granting College Board permission to sell your GPA, SAT and AP scores, potential major, religious affiliation, race, zip code, and family income to other entities. Not only that, but your inbox will be flooded with spam and promotional offers from colleges you have never even heard of.

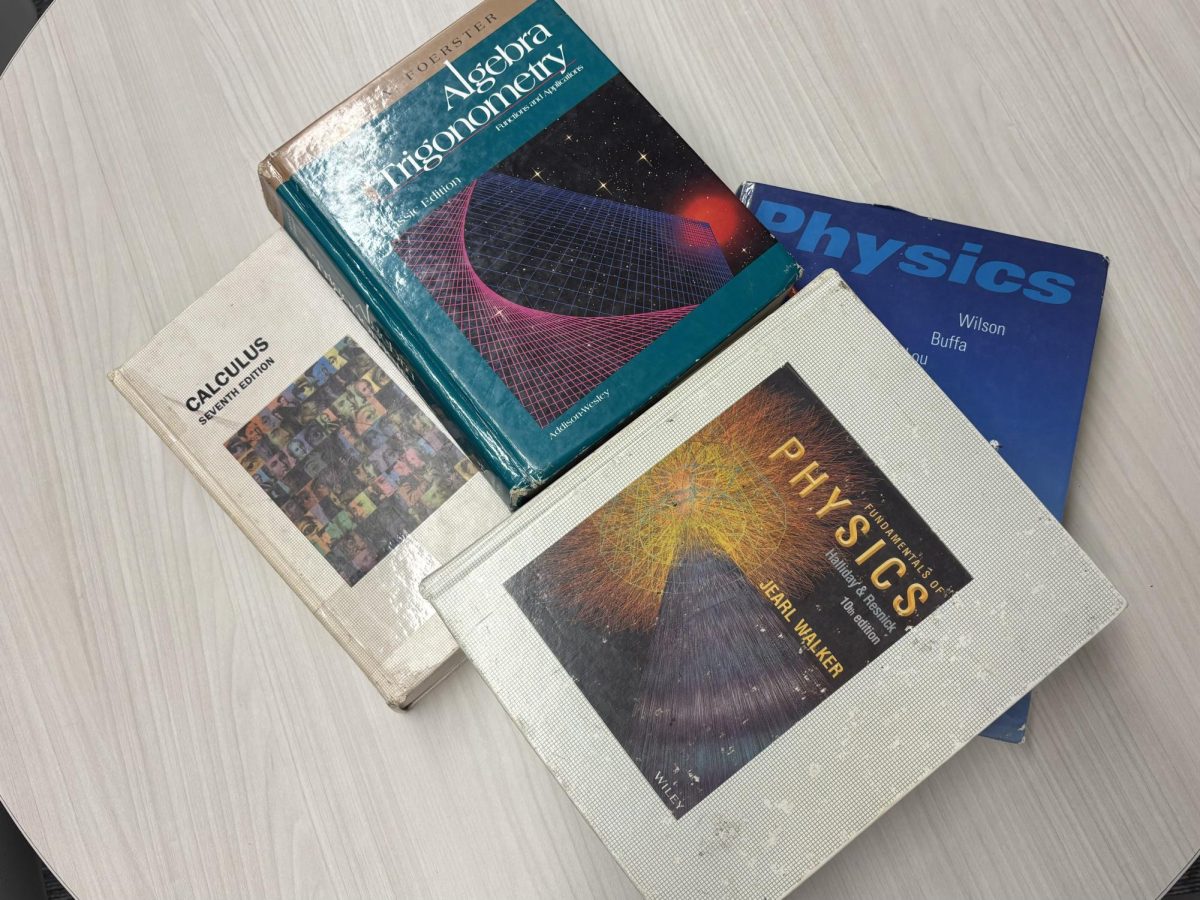

If you have taken an AP class or an SAT, you are likely familiar with College Board’s many unique ways of asking for more money. In fact, their entire business model is centered around just that. Each SAT has a $60 registration fee, an additional $30 for late registration, a $25 fee to change your testing center or cancel it, a $35 fee to cancel your test after the deadline, and a $14 fee to see your answers. For the AP tests, it is $98 per test, with a $40 late fee. While the College Board claims that they are “committed to excellence and equity in education,” they continue to place any helpful resource behind a paywall, and do not plan on reducing prices. To ensure that people continue taking the SAT multiple times, their score release schedule is designed such that if you are not confident in your score, you would have to register for another SAT before being able to see your past score, unless you are willing to pay the extra $30 for a quicker score, or the $30 late registration fee.

With this many fees, one would hope that College Board would have effective administration and few to none errors concerning their services, but this is not the case. Following their 2021 AP exam cycle, countless students, especially in Georgia, reported missing scores in their AP accounts. Students attempted to contact the College Board to see what had occurred, but their response was far from helpful. A student at Chamblee High School reported that the College Board “said that I never even took the test originally, but then when we talked to the AP coordinator here at school, they confirmed that I did take it and that they had sent the records, and eventually they just stopped giving us a clear answer on what happened.” Not only have these students been cheated of their hard work, but the College Board has expressed no interest in solving the countless problems they have caused for those students.

As many juniors and sophomores may know, the SAT has gone digital, and nine AP tests will as well within the next year. For the College Board, it means reduced expenses in printing materials, mailing of test packages, test collection, and grading. For us, it means a new test with little to no precise study material available, a fully different format that has many SAT tutors quitting, as well as the same registration fee of $60. In fact, next year they plan on raising some of their fees, no shock there. The College Board defends their pricing, claiming it is in place to “ensure consistency for students and educators.” They also claim that Digital SAT will ensure more accessibility to the exam, and because it is shorter, online, and adaptive, it will be more attractive to students. However, if they truly valued accessibility, they would be reducing the price to match their past profit margin, as an ethical “not-for-profit” should.

These numerous examples of College Board’s past negligence reveal a worrying pattern of prioritizing profit over educational integrity. Is the College Board truly deserving of their charitable status or are they more driven by generating profit that pays high salaries, fueled by their monopoly over the American education system? The approach the College Board has taken can be questioned at the global, federal, state, and individual level, which leads many to ask what can be done to solve the issue. It’s time for the College Board to either adjust its financial priorities and practices to better align with the ethos of a nonprofit or engage in for-profit practices and pay the justly owed taxes on them. It will benefit the College Board’s reputation if they can return to promoting “excellence and equity in education.” The path forward may require a collective effort to prioritize the future of the American education system over profit, built on a foundation of fairness, accessibility, and excellence.