Artificial Intelligence

Terminator, Hal, Blade Runner. Science fiction has long speculated about the ramifications of artificial intelligence, and now we have seen a boom in real AI progress. With new AI, formally called Large Language Models (LLMs), drawing increasing attention, we see a rise in machine learning that mimics humans frighteningly well. Let’s be clear: this technology will not become Terminator or Hal anytime soon. All LLMs do is use a large dataset to predict the next word in a sentence. This means they are not sentient, just impersonating a human’s writing. That does not mean that their capabilities are not concerning. It is now harder than ever to tell if an audio clip, piece of text, or image was human made. This is especially troubling for teachers, who are seeing a rise in AI written essays and homework assignments. So, I sought to comprehend how our education system as a whole is reacting to this technology.

Teachers

Alan Turing, a British computer scientist, came up with a simple test to determine machine intelligence. If it can convince humans it is a human, it passes. This is known as the “Turing Test”, and I ran a miniature version of it at our school.

I got three different students to write a paragraph on whatever topic they wanted, then generated a paragraph on the same topic using the new Chat GPT-4 model. Then, I approached several different English and Social Studies teachers to determine whether they can tell the difference between a student written and AI written piece. During the experiment, I asked them how they reached their conclusions. Teachers who spotted poor prose or grammatical errors tended to assume that the piece was student written, speaking to the polished quality of AI work. They mainly focused on style, picking what they considered as more “generic” work to be AI generated. While all the teachers were confident in their ability, only one teacher managed to get all three correct: Mr. Robert King! When asked about his thoughts on AI, he responded: “We must learn to work with it, so we are not controlled by it.”

The rest of the teachers I interviewed managed to get at most one correct.

Mr. Spear pointed out several issues with this experiment. For one, the prompt wasn’t teacher-crafted. To confront the presence of AI, he does journals with his students at the beginning of every year, and other humanities teachers will do similar exercises. Throughout the year, teachers will learn your writing style and be able to distinguish your voice. They will also be able to compare your in class writings with out of class writings. These factors make it easier for teachers to tell what is AI and what is not. While this experiment contains flaws, it demonstrates the indistinguishably human-like writing skills of AI.

Some teachers are inclined to use an AI plagiarism checker. So, I ran all of the paragraphs into three AI plagiarism checkers to see how effective they were. They consistently identified the AI written work. However, not only was it easy to bypass them by rewording the AI’s words in a more human manner, they also tended to mark student written work as AI written. One of the websites even gave a piece I wrote about the Soviet Union’s collapse as having an 100% chance of being AI written. So, these softwares are prone to false positives and can be tricked. If a teacher considers using these sites, it might be wise to think twice before using it as the sole reason to accuse a student. AI contains massive potential to enrich the learning experience, rather than being a detriment. To look at the potential benefits of AI, we must turn to the online educator community.

Online Educators

While many students use AI as a shortcut to make work easier, it is not confined to that. Some educators see it as a tool that has the potential to individualize learning. Online courses like Khan Academy and Harvard’s CS50, which teach beginner programming, have embraced using AI as a boon to education, not a hindrance. Khan Academy uses “Khanmigo” and CS50 uses the “Rubber Duck”, both of which are AI tools that ask you to talk through the process of solving a problem to point you in the correct direction, without revealing the answer. Sal Khan, creator of Khan Academy, says that it has the potential to be “an amazing, artificially intelligent teaching assistant”. Harvard Professor David J. Malan describes the “Rubber Duck” as a way to “approximate a 1:1 student teacher ratio,” and has seen positive feedback on its impact on students. So, there is a future for AI that cooperates with both students and teachers. This begs the question: If AI has such a large potential to boost learning, why is it approached by students primarily as a method to take a shortcut?

Students

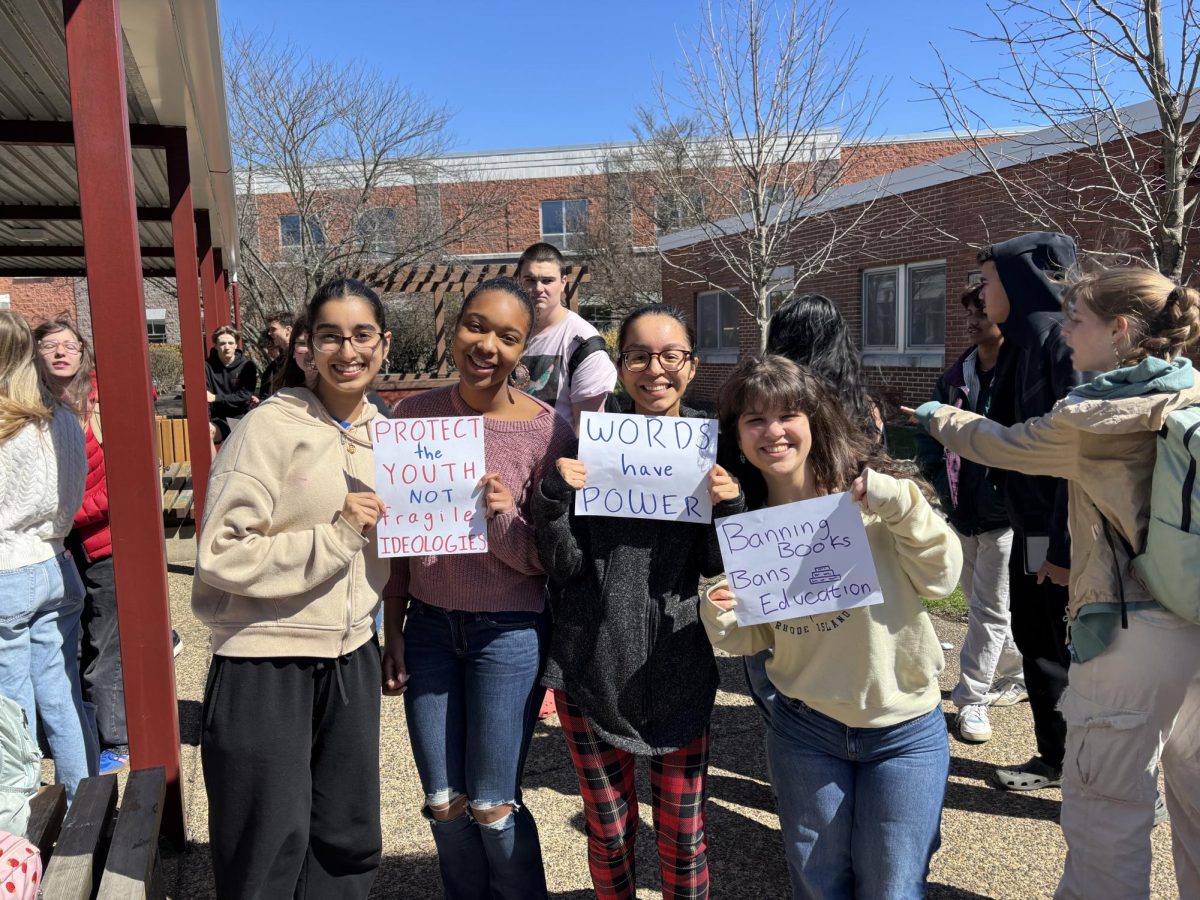

The problem of students using outside resources has plagued teachers since the dawn of the internet age. Programs like PhotoMath and Wolfram Alpha can solve math problems, and sites like SparkNotes hold many insightful summaries on books. They share a similar perceived purpose to AI: Although a student will understand the material less, using them expedites the task. Students across America rely increasingly on these tools, as well as generative AI, to manage increasing course loads. COVID-19 accelerated a mental health decline, which has been deemed “a national mental health crisis” by the American Psychological Association. These stress issues correlate to increased cutting-corners: In a college survey, 59% of respondents admitted to cheating. Of those 59%, 72% of them say they cheated because of pressure to do well. In an increasingly stressful learning environment, it does not seem fair to address cheating solely as a blemish on the moral character.

Learning About Learning

Were you an avid reader when you were younger, but now hate reading books for English class? Did you like to doodle, but never enjoyed art class? There is a reason. In 1973, researchers gathered a group of students who enjoyed drawing. For one group, they told them that if they drew well, they would get a prize. The other got no award. After examining their behavior a few weeks after the test, the group that received prizes were drawing significantly less, with less effort put into their drawings. This is an example of the “overjustification effect”, when our innate desire to do a task becomes obscured by a goal and reward system that dulls our yearning to accomplish a task. Yet, during our formative schooling, grades become the sole priority. Students and faculty alike perpetuate this pressure constantly, whether they know it or not. The message is resoundingly clear: A worse grade means you are less smart, less capable, or less diligent. It is a fight upstream for any student who enjoys learning to keep their passion alive and not replaced by a fight for the highest marks.

When reflecting on the classes that left the biggest impact, they were ones I did not get the best grade in at first, then improved. This is because in those courses, I had the most to learn. Despite this, we are told that “you would rather get an A in an advanced class than a B in an honors class” because it boosts GPA. Challenging oneself in a more rigorous course was discouraged for the sake of improving grades. So, when I thought about my courses, all I worried about was pushing the boulder of my GPA up a hill. How many points can I squeeze out of these assignments, while doing as little work as possible? There’s a method that every student eventually learns: the way to game the system. Churn out work that’s just good enough, not work you’re proud of. Memorize for tests, then forget to make way for the next cycle. If you don’t, you fall behind. At that point, there is little reason for a student not to use an AI. If the goal is to produce generic, good enough work, AI can do that perfectly. We blame individual students for misusing these new technologies, but ignore the underlying issue.

AI has its issues when it comes to education, yes. The rise of harder to detect plagiarism will lead to a tsunami of student-teacher trust issues we are not prepared to face. More fundamentally, however, the recent surge of AI calls into question how we as students are learning to learn. Although AI can amplify learning by acting as a teaching assistant by explaining concepts, students are not incentivized to use it in that manner. So, are we being taught to be smart? Or are we being taught to be artificially intelligent?

Can You Tell What’s AI? (Bonus)

Below are the six paragraphs I used to test the teachers. Can you do better than them?

Topic A: Women in Stem

#1A: Being a young woman in a technology-based field can be a challenge. In any room of 100 people with a technology-related bachelor’s degree, odds are that only 21 of those people will be women. Additionally, the lack of female role models available makes it so young women and girls have a hard time seeing themselves in such a field, as opposed to more female-led fields, such as nursing and teaching. An added challenge comes in the form of balancing schoolwork, social life, and extracurriculars. Trying to prove yourself in a male-dominated field adds even more pressure. Despite these challenges, many girls push through because they’re passionate about science and technology and want to make a difference.

#2A: Being a young woman in a tech field involves facing numerous tough and discouraging challenges. A big issue is the ongoing gender stereotypes that claim women aren’t as capable in STEM areas, which can hurt their confidence and make them feel like they don’t belong. Plus, the gender pay gap is still a huge problem, with women often making less than men for the same jobs, which is both unfair and demoralizing. Finding mentors and role models is also difficult since there are fewer women in high-ranking tech positions, leaving them with less support and guidance. Additionally, juggling a demanding tech career with personal life, especially when thinking about starting a family, adds another layer of difficulty, as many tech jobs require long hours and high levels of commitment. Despite these hurdles, many young women are pushing through and making their mark in the industry, but the journey is definitely challenging.

Topic B: Pokémon

#1B: Playing Pokémon has always been a nostalgic and exciting part of my life. I still remember getting my first Game Boy and a copy of Pokémon Red as a kid, spending countless hours exploring Kanto and trying to catch as many Pokémon as possible.

The thrill of encountering a rare Pokémon in the wild, figuring out the best team strategies, and finally beating the tough gym leaders and the Elite Four are memories I hold dear. Trading and battling Pokémon with friends added a fun social element that made it even better. As new games and regions came out, I stayed hooked, enjoying how the gameplay evolved and the roster of Pokémon expanded. Whether it’s battling in tournaments, hunting for shiny Pokémon, or just exploring new regions, Pokémon has been a constant source of joy and a great way to escape into a world full of adventure and friendship.

#2B: Pokemon is a popular video game franchise. I greatly enjoy Pokemon games, as the easy accessibility of playing and charming, collectible creatures that are found in them make for a good experience. Additionally, the game also contains a surprising amount of depth and strategy upon a closer inspection, which has created a thriving competitive scene that I have occasionally dipped my toes into. I played quite a bit of Pokemon on my DS when I was younger. After a significant stretch where I grew disinterested in it, I returned to playing it via an emulator on my computer, and have found that there’s a lot of enjoyment still left in catching them all.

Topic C: Fall of the Soviet Union

#1C: The fall of the Soviet Union was set into motion primarily due to its infrastructure being unable to keep up with the United States. When Mikhail Gorbachev took over in 1985, the country was already facing an economic crisis, with high unemployment rates and poor infrastructure. He befriended the United States President Ronald Reagan, and enacted the policies of Perestroika and Glasnost, which refer to a restructuring of the economy and openness of the press. Additionally, Gorbachev stopped using the Soviet military force to put down protest movements for sovereignty by the Soviet states. This led to the fall of the Soviet Union on Christmas Day, 1991, and the emergence of the United States as the sole global superpower.

#2C: The primary reason the Soviet Union fell was its failing economy, which was unable to sustain its political structure and global ambitions. Throughout the 1980s, the Soviet economy was plagued by inefficiencies, stagnation, and a lack of innovation, largely due to its rigid central planning system. The heavy military expenditures during the Cold War further strained resources that could have been invested in the civilian economy. Additionally, Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost (openness) and

perestroika (restructuring), while intended to reform and revitalize the Soviet system, inadvertently exposed its weaknesses and hastened its collapse. The increased transparency allowed citizens to voice their discontent and demand change, while economic restructuring failed to deliver quick improvements, leading to widespread dissatisfaction. Ultimately, the combination of economic decline, political reforms, and the rising demand for independence among Soviet republics culminated in the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Correct Answers (AI Written):

Topic A: 2

Topic B: 1

Topic C: 2