As of 2017, women complete only 38% of undergraduate math majors and 29% of all math PhDs. Female professors make up a mere 12% in math PhD programs. Each step into the academic world of mathematics, the percentage of women decreases. But what’s the data in Radnor?

At Radnor High School, female students make up 28% of physics C. 27% in Multivariable Calculus and only 23% in Seminar Algebra II. Despite an overall population of 48% women, men still hold a significant majority in some STEM classes. But why? There are a few possible answers.

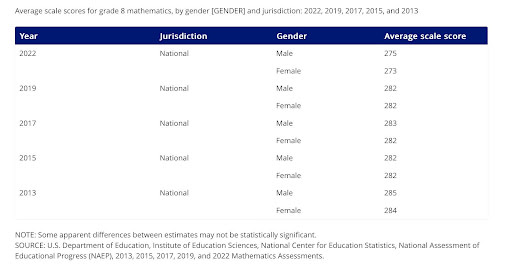

Consciously or not, women of all ages are impacted by society’s tendency to prefer men in mathematics, despite studies proving that there are no biological differences in math ability. For example, eighth grade female students earned at most 2 average points different in math as concluded by 5 studies covering 9 years. Yet, the belief in a man’s “‘innate’ math ability” remains. Biases instilled at a young age can negatively impact women all through their life, but the burden begins by directly harming young girls’ performance and motivation in their math classes.

Other societal pressures also play a large role. RHS Senior Charles Yang hypothesizes “it’s more the fields that you’re pushed into when you’re younger” than high school influences that skew gendered interest in STEM. Plus, STEM toys are often gendered, with 31% being targeted at boys and 11% at girls. This marketing causes more young boys to experiment in STEM, pushing them into higher math tracks and STEM classes than their female counterparts. By age 6, young students are more likely to view men as a better fit for STEM jobs than women. Even kindergarteners have consistently rated women lower in terms of math capability and enjoyment.

Beyond societal influence through toys and other media, young scientists often can’t find female role models in STEM. Teaching about female scientists and mathematicians from a young age, such as Katherine Johnson, Rosalind Franklin, Sally Ride, and Ada Lovelace could increase girls’ STEM aspirations and confidence to pursue math or science. You can read more about these amazing women and others here. Ultimately, if young girls don’t have strong role models in STEM, they may not see themselves succeeding in these careers, and are less likely to pursue STEM in their higher education and beyond.

Additionally, gender dynamics may also cause STEM classes to be less enjoyable for girls. “I do feel like… the girls gravitate towards each other because a lot of the time… it’s easier to work with the other girls in the class because I know” they’ll be respectful, RHS senior Alison Long describes. She takes Multivariable Calculus and Physics II, two of the highest level math based classes offered at Radnor. She also mentions, the separation “isn’t necessarily because they’re guys.” Oftentimes, though, it is. Senior Rhea Howard, who also takes Multi and Physics II, along with Physics C, explains how a “boy’s club” culture may impact the phenomenon: “[The guys] often only talk with each other and they’re super loud and they don’t include everyone in the class in their discussions, or they don’t take a girl’s answer until it’s confirmed by another guy or the teacher.” Some female students may not want to participate in this competitive environment, especially since, often, male students are more confident in their mathematical ability than females. Confidence, though sometimes beneficial, can lead male students to trust their own work more than others, thus dismissing female contributions. “[And so] you have to prove yourself as a girl to the rest of your class,” Rhea explains. These unhealthy dynamics can be isolating, causing discomfort and furthering the academic divide in the classroom.

Unfortunately, off-balanced social dynamics cause off-balanced collaboration, and in a system where consistent collaboration is vital to learning, the gender divide is further exemplified. When placed in a healthier environment, such as an outdoor classroom away from the typical math class, girls consistently outperform boys. But such an unconventional learning environment is rarely a viable option, so gender dynamics stay unbalanced. This can be intimidating, resulting in girls shying away from STEM when they look towards their higher education. Alison suggests, “If I were taking classes with all guys in college versus here [it would be different] because here I’m so used to everyone.”

Similarly, though less common, inappropriate and misogynistic comments remain present in STEM environments. In the workplace, math and science academia has the second highest rate of sexual harassment, (military being the first). In undergraduate education, too, female STEM majors are subjected to higher levels of sexual harassment than other majors. Sexual comments, or even jokes, in work or school, can cause discomfort in an environment that should feel safe. These comments are not exclusive to STEM classes, but they are common and exemplified due to gender imbalance. Even seemingly small but clearly inappropriate comments further complicate social dynamics and result in more women being pushed away from STEM fields.

Despite it all, many women pursue their STEM passions, working harder than their male peers to earn the same degrees and jobs. If you’re interested in supporting women in underrepresented STEM fields, encourage your female friends interested in STEM, support women in STEM organizations, and do your research. And please pay attention to your own actions, because the things you say and how you treat others makes a difference.