Listening to my teachers during class used to feel like HIIT cardio, eight periods a day, five days a week. I strained to hear each word amidst background noise, to mentally string the words together, to make sense of them all the while taking notes and actively following along with the lesson. It was draining. My grades slipped. I had a hunch something was wrong. And soon an audiologist confirmed it—in December of my sophomore year, I was diagnosed with a neurologically-based hearing impairment. About a month later, I was handed a pair of sleek hearing aids, along with an FM microphone with direct sound-transmission capabilities. My teachers could wear it during class to bring their words straight into my ears. This clip-on black microphone, which I later nicknamed Elvis, was an academic game-changer. I no longer had to work so hard to hear; sound became filtered and smooth, not obscured by the background noise of classrooms nor muffled by my own brain. Elvis, the size of a small thumb, served as my personal escort into the wonderful realm of assistive technology (often abbreviated as AT).

Assistive technology is a relatively modern term, but it is not at all a modern concept. The Assistive Technology Industry Association defines AT as “any item, piece of equipment, software program, or product system that is used to increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities of persons with disabilities.” ( https://www.atia.org/home/at-resources/what-is-at/) In other words, it can be anything that helps a disabled person function in society— high-tech and electronically intricate like my Elvis, or low-tech, like a picture communication board. It can be expensive, or it can be cheap. It can be big, or it can be small. But no matter the size, price or degree of complexity, assistive technology changes lives. For students, it crushes the disadvantages that come with disability; it empowers access to academic opportunities. And in Delaware County, public school students in fifteen districts have a unique avenue through which to discover effective, meaningful AT solutions.

The Delaware County Intermediate Unit (DCIU) Education Service Center in Morton, just outside of Philadelphia, is home to an Assistive Technology Lending Library ( https://dciu.myturn.com/library/inventory/browse) and the highly experienced trio that manages it. I partnered with Mrs. Rudisill (who worked at DCIU before becoming one of Radnor High School’s assistant principals!) to get in touch with the AT team. Soon I was in contact with Jason Gonzalez, one of the assistive technology team members, and we set up a time for me to go see the Lending Library in person.

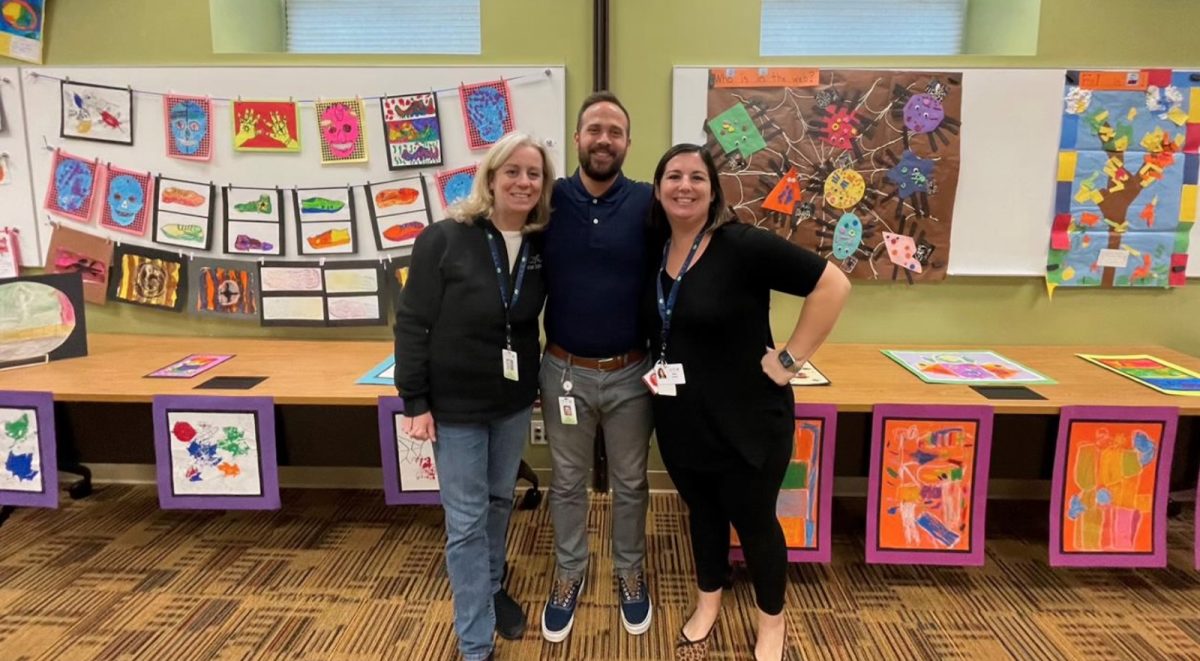

Shortly after noon on a sunny Friday, Mr. Gonzalez brought me into the Lending Library, which consisted of a room filled with 3D printers (more on that later), a table covered with laptops and papers, and a storage room where the AT equipment itself was held. He introduced me to his colleagues, Nora Connell and Marisa Giannini. Ms. Connell, a former speech therapist, had worked at DCIU for over thirty years. Ms. Giannini and Mr. Gonzalez had previously been special education teachers in Delaware County—Mr. Gonzalez taught special education in Upper Darby for a decade and a half before joining the Lending Library team a few years ago. But at that moment, all three of them were sitting at the table, diligently sorting through pieces of assistive technology and managing the Lending Library website.

I sat down next to Ms. Giannini and asked some fundamental questions about the program. How does it work? How is it funded? What are the ins and outs? DCIU has two Lending Library programs—one for STEM equipment (this library is directed by another team) and one for assistive technology, available to students with disabilities across Delco. The AT Lending Library, federally funded through the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), loans out assistive equipment for 63-day trial periods so that districts can determine whether or not a piece of technology will be helpful to a student before actually purchasing it. Teachers, administrators, support staff and other professionals can all request a free equipment trial through the Lending Library website, which was built two-and-a-half years ago and features a helpful reservation system. This system allows website users to see when a piece of equipment will become available and adds them to a digital waitlist.

The popularity of the AT Lending Library has grown significantly over the past few years, namely due to the new website and the team’s outreach and awareness efforts. Last school year, the Library loaned out 160 devices, but at the time of my interview, it had loaned out 260 devices and was on track to approach 300 by the end of the 2024-2025 school year. This year, the team launched an influential new project called AT On the Road, which allows them to bring equipment to over half of the public school districts in Delaware County and connect with special education professionals and teachers. Ms. Connell stressed the impact of this program, commenting that “there are kids out there in districts that need devices or supports, and the teachers don’t know that there are things that we have available. So we want to get the word out. We need to go through teachers, because they’re the ones who know the individual students.” Mr. Gonzalez noted that the Lending Library’s Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/dciu_at/) and YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLVSPMTVmAs4Hy_h5qvCI8F_qNkQ6fNkn0) accounts also spread awareness of the program: “Somebody today reached out about a post I made this morning and asked “is that device available?””

“More often than not,” device trials are successful, according to Ms. Giannini. Mr. Gonzalez jumped in, saying that trials always run more smoothly when the AT team is involved and providing direct support; “the more involved you can be, the trial will go more successfully and the student will see a benefit. That translates often to districts making a purchase.”

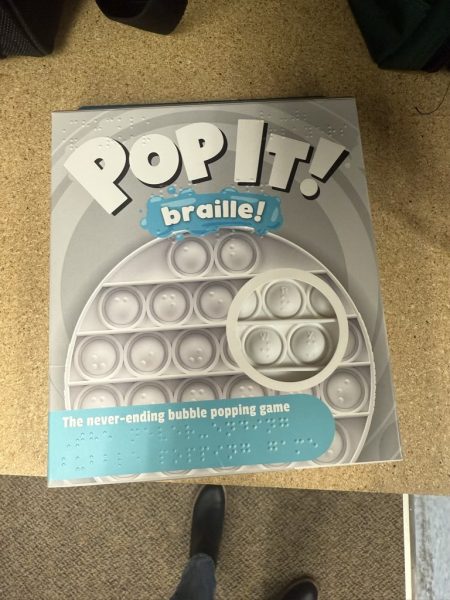

The AT Lending Library loans out equipment to students with all kinds of disabilities, from motor impairments to blindness to communication deficits. “Every disability category is represented,” said Mr. Gonzalez. Thus, assistive technology in the Library is sorted into multiple diverse categories: adaptive gaming, augmentative and alternative communication (AAC), blindness and visual impairment aids, computer access, mounting (attaching equipment to wheelchairs, desks, etc.), recreation and leisure items, sensory toys, smart home technology (a new category this school year), switches, and therapy tools for reading, writing and math. Sidenote—the AT Lending Library does not loan out hearing equipment. That’s done by the DCIU’s Audiology Department.

Toys are often loaned out to preschools, elementary schools and early intervention programs. Adaptive gym and gaming equipment usually goes to middle and high schools. But some kinds of technologies are often loaned out for students aged three to twenty one, such as AAC systems. And one thing is for sure: all of these assistive technologies, no matter how complex, have the potential to alter the academic trajectories of disabled students for the better.

Once I had learned about the operations of the AT Lending Library and the duties of the AT team, Mr. Gonzalez took me on a tour of the storage room, and I got to see numerous pieces of impactful technology. The room, a little smaller than an average classroom, was packed with tall black shelves and cardboard boxes and plastic storage bins meticulously labeled with sticky notes. Mr. Gonzalez explained to me the difference between high-tech, mid-tech and low-tech tools. High-tech equipment, he explained, is often downloaded on locked-down Apple iPads, while mid-tech systems are typically battery powered and can create single messages or present a few choices. Low-tech AT may not even use electricity at all.

Switch Interfaces and Computer Tools

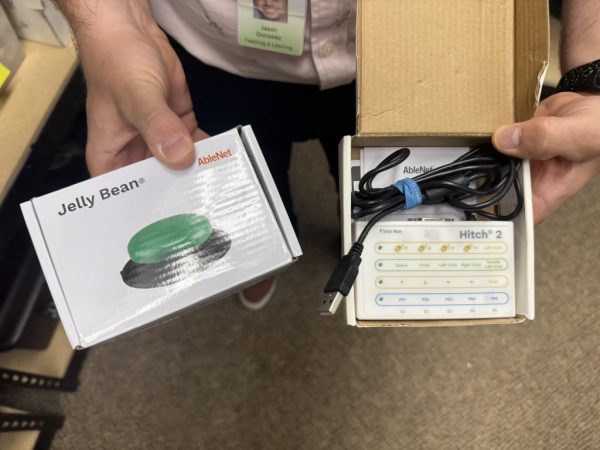

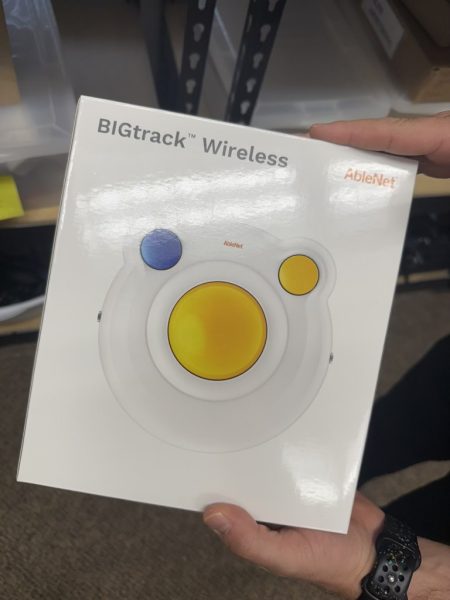

Students with motor disabilities like cerebral palsy often have trouble using computers and traditional electronic devices. But creative systems in the Lending Library, like a Hitch system, can remedy these challenges. The Hitch allows mechanical buttons, switches or joysticks to take on traditional computer functions like clicking and scrolling. Similar systems in the AT Lending Library are Bluetooth compatible, like the BIGtrack Wireless roller in which a central yellow ball takes on the role of a mouse.

The Library holds many other tools that allow for accessible computer use. A pen-shaped mouse provides users an easier grip. Microsoft adaptors allow compatibility with a variety of devices and applications. One mouse in particular performs a crucial job–it can be adjusted to compensate for tremors, or hand-shaking, so that individuals with these conditions can exert greater control over a computer mouse. The mouse can be programmed for many tremor frequencies and severities, making it a truly valuable and adaptable tool.

Entire shelves are filled with buttons and switches of all shapes, colors and sizes. Some are mechanical buttons, which can only be triggered with a preset pressure. Some are electrical and frequency based, so they can be programmed to respond to different levels of movement, which is important for students with very limited mobility. All of these buttons and switches can be mounted to wheelchairs. For instance, someone who cannot move their hands might have a button mounted to the headrest, and they can bump their head against the button to perform a certain function.

Therapy Tools and Gaming Equipment

Early Intervention programs, which serve pre-kindergarten students with disabilities, are often the biggest borrowers of therapy tools. These devices can be employed in speech therapy, occupational therapy and more. Many of them feature bright lights and colors, which are particularly helpful to children with traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) or visual impairments. On a high shelf, I saw a massive pair of scissors attached to a stand. Mr. Gonzalez explained that these scissors can be connected to the buttons and switches we saw earlier to help students with motor impairments. With the press of a button, these scissors “allow the student to do an activity, not the adult. It lets them be as independent as possible.”

Mr. Gonzalez then showed me the adaptive gaming equipment, a component of assistive technology about which he is especially passionate. Over many years, he has learned to adapt almost any video game system to meet the needs of students with disabilities, allowing them to be included in the popular pastime. I only saw one adaptive gaming system on the shelf at the Lending Library–that’s because most of these systems have been lent out to middle and high schools across Delaware County!

Next to the nearly-empty adaptive gaming shelf, I saw a box labeled “Cosmo.” These Cosmo systems come with six mechanical buttons, and they can be paired with iPad programs to facilitate therapy activities, music tools, math games and more. “This is a very therapeutically engaging system,” said Mr. Gonzalez. “For example, the buttons can be placed around a student who is working on reaching skills.” Like the gaming devices, Cosmo systems are always in high demand among teachers.

Technology for the Blind and Visually Impaired

An entire stack of shelves in the Lending Library is devoted solely to pieces of AT that help students with impaired vision. The shelf is packed with magnifiers, which can often be held in one hand. These devices can help a student read text with higher contrast or greater amplification. “But they’re really small and portable, very subtle,” Mr. Gonzalez said, “so you can just pop it out of your bag if you need it!” These magnifiers are discrete, to the joy of self-conscious older students. Other magnifiers are desk-mountable, so they can amplify text much more powerfully. Many of these devices have cameras that magnify the classroom on a secondary screen, so students can see both their textbooks and their teachers.

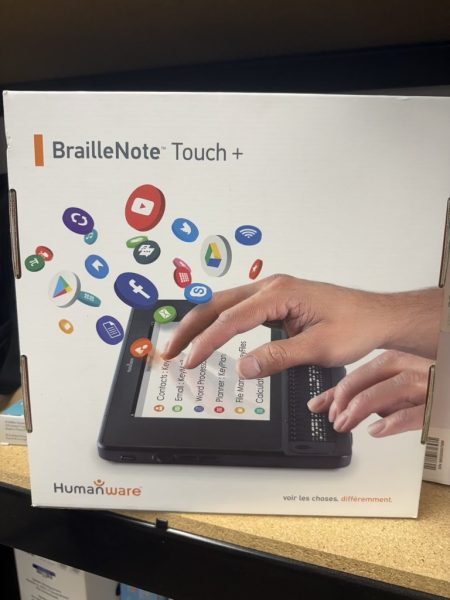

Next to the magnifiers is a collection of bulky Braille keyboards. Braille, a tactile language for the blind and visually impaired, is configured in six cells; depending on the configuration of dots in each cell, various letters can be written. The keyboards, such as the BrailleNote APEX, help visually impaired students to type using Braille. The Lending Library also houses devices that are more suitable for inexperienced Braille users and Braille learners. BrailleNote Touch, another device, converts digital text into refreshable Braille. This means that blind students can read social media posts, articles, documents and web browsers, just like their typical-vision peers.

Recreation and Leisure Tools

While assistive technologies for recreation and leisure may not be academically necessary, Mr. Gonzalez says that “we want to make sure everyone has access to these fun activities.” School district Physical Education Departments often reach out to the Lending Library looking to secure gym equipment for their classes. One tool Mr. Gonzalez showed me was an adaptive lever system. This system can be connected to a baseball bat, hockey stick or tennis racket, and it allows students to pull a level to move the sporting equipment. “If they can pull, they can play,” said Mr. Gonzalez, swinging a red baseball bat with the device.

iPad-Enabled Systems

The entire back wall of the storage room holds bins of iPads, carefully organized by software and generation. Writing, reading and math tools are downloaded onto the iPads, as well as advanced communication systems for students who are nonverbal or have minimal spoken language. These iPads are all locked down, meaning that only apps downloaded by DCIU are accessible to students.

Ms. Giannini explained some of the challenges that come with loaning out iPads. A few years ago, students and teachers were able to set their own passcodes on these devices, so DCIU AT staff were locked out of them when they were returned. Eventually, a standard passcode was established across all the devices. Ms. Giannini also says that students often leave identifying information on the iPads, especially if they need to take photos or audio recordings for personalized AAC applications. “It’s a lot of trial and error,” she told me. “As situations come up, we have to constantly adapt.” Overall, however, iPads make software system lending much easier, and they are accessible for the students with communication challenges who need them most. Last year, Ms. Giannini worked with a fourth-grader with limited communication. When she gave the student a trial device, the girl went from using AAC ten minutes a day to the entire school day, all within the span of one week. “She picked it up and took off!” says Ms. Giannini. “It was just so wonderful to see her taking full control of it.”

The Maker Space

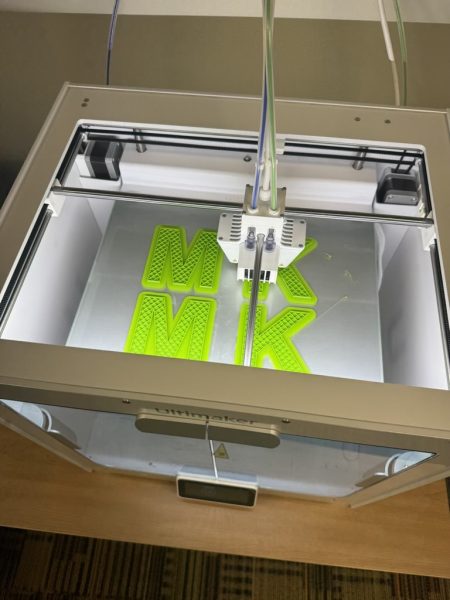

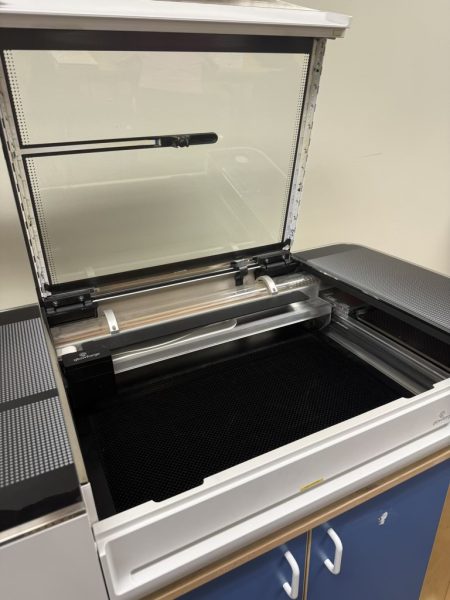

The room with the big table also holds the Lending Library’s unique Maker Space, which holds tools that the team can use to create individualized pieces of equipment for Delco students. Three 3D printers sit along the back wall of the room; one of them was actively chugging away, creating a set of bright green plastic letters for use by a speech therapist. The black printer, a newer purchase, enables the team to print items as large as a basketball.

Mr. Gonzalez uses CAD, or computer-aided design, to create customized tools for his students. He can often find files for free online, adapting them for individual kids, but sometimes he has to create his own devices. “I just made an adapted armrest!” he told me. “I had a student whose arm was drifting inward, so in a CAD system, I built a plate with openings to be able to strap it onto a wheelchair, and it had a riser to compensate for the height of the student’s arm and a cradle where the arm would go. He can rest his arm in there so he can use other devices by moving his wrist!” Mr. Gonzalez also prints many keyguards for AAC systems – these are printed pieces of plastic with openings for different icons on an iPad. Some students find it hard to type on a device where buttons are not divided by barriers, so these keyguards can make AAC systems even more accessible.

Additionally, the Maker Space features a 60 Watt laser cutter that can slice through wood, acrylic and even metal. Digital software helps the AT team control the position of the laser, which is used to cut keyguards, eyegaze boards and laser-etched letters and numbers.

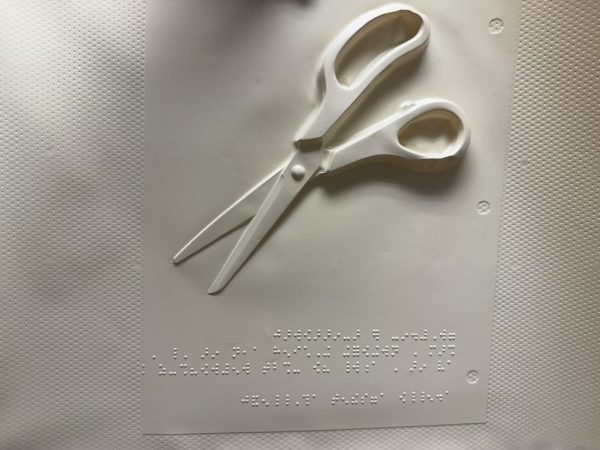

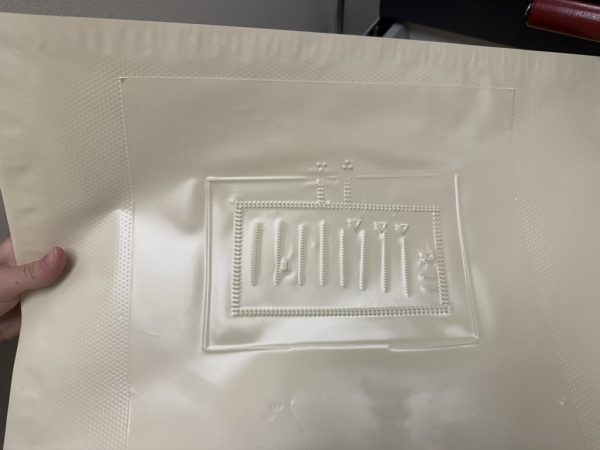

Next to the laser-cutter is a massive device called a thermoform machine. This machine serves as a Braille duplicator that can create many copies of papers written with tactile dots. Not only can the thermoform machine duplicate Braille, but it can also create tactile duplicates of objects or diagrams for blind students. Teachers of the visually impaired use the thermoform machine to print grids or graphs for math classes, diagrams of cells for biology, maps for geography, etc. Mr. Gonzalez showed me two print-outs from the duplicator: one had a perfectly sculpted tactile image of scissors and a Braille description of them underneath. The other print-out was requested by an orientation-mobility specialist, a teacher who helps blind and visually impaired students learn to navigate in space. It had a tactile map of a local Target store, denoting the isles and using symbols to show cash registers.

While managing Lending Library might be the primary responsibility of the AT Team, the trio has found methods outside the scope of assistive technology to help Delco students with disabilities.

It all started with Ms. Connell and one of her students many years ago, a young girl with autism who adored the Muppets. This girl liked to draw the Muppets characters, cut them out and tape them together to create detailed scenes. Ms. Connell realized that “They [students with disabilities] have different skills that they don’t always get to demonstrate and exhibit. Let’s celebrate that!” So, three years ago, Ms. Connell, along with Mr. Gonzalez and Ms. Giannini, established the annual ArT Showcase, a gallery-like environment for disabled students to display their artwork. In 2022, the first year of the gallery, 500 pieces were submitted to the AT team—artwork filled two entire conference rooms to the brim! These works, created by preschoolers, elementary schoolers, middle and high schoolers, were celebrated in a unique environment focused on the needs of disabled students. Drawings, photography and sculptures adorned the conference rooms, where proud families could admire their kids’ pieces.

Ms. Giannini told me that some individuals at the gallery were even interested in purchasing artwork. In 2022, the showcase held a massive canvas painting created by students at CADES, a program for kids with physical impairments. A CADES art teacher built a swing that could hold students and their wheelchairs, and he put students on the swing and handed them paint brushes or other art materials. While swinging over the canvas, they added their own special touches to the piece, creating a fascinating abstract effect.

For this year’s gallery, the team was able to expand into a bigger space: three whole rooms and the hallway between them were filled again with art. Additionally, they brought in a music teacher this year so students and their families could appreciate student art while listening to disabled young adults beautifully playing the guitar and the keyboard. “Part of it is to help get the word out that people who learn differently have talents,” says Ms. Connell, “and unless you provide opportunities for them, you would never know about those talents.”

Before I left (after all, it was now late afternoon on a Friday), the AT team told me all about the things they’ve learned from managing the Lending Library. Ms. Connell stressed the team aspect of this program and how the trio’s dynamic is critical. Each one of them has different specialties, and they’re all able to work together to find the best solutions for Delaware County students who need them.

Ms. Giannini said that she’s learned how “it’s ok not to know everything all the time.” Working with assistive technologies means that troubleshooting is a daily occurrence, and with systems being updated and renewed almost constantly, it’s hard to stay up to date on all the newest information. She has been empowered by her work in AT, always learning about new technologies, saying “I don’t know, I’ll learn more and get back to you.”

Mr. Gonzalez told me about how fulfilling it is to be part of this program. “When you learn about a killer new feature that can help a kid take off,” says Mr. Gonzalez, “those moments are the best.” He recently worked with a young man to find a predictive typing feature on his device. This student advocated for himself, telling Jason “this is all I need, thank you.” And with his new feature, he was able to excel in school.

Mr. Gonzalez has also noticed that students can be afraid of social stigma and ostracization from using their assistive devices. As an AT user myself, I can totally relate to the feelings of (irrational) embarrassment that can sometimes rise from needing technology to access the curriculum like my typical peers. He said that by giving students a measure of control over their supports, it empowers them to actually use AT. A middle schooler he worked with last year was hesitant about using a text-to-speech program because of the attention from peers and the awful computerized voice. Mr. Gonzalez did some research and was able to download the fun AI-generated voices of “robots, valley girls, and Glinda.” The student got to pick a new voice for his device, and this allowed him to feel more confident. And his peers thought that the voices were pretty cool, too.

I left the Lending Library that day with a smile plastered on my face. Assistive technology has transformed my own life, and I cannot even begin to describe the joy that came with seeing accessible AT for thousands of students in our region. The Lending Library is a beacon of hope for students with disabilities and their teachers, who are looking for solutions that work without having to purchase devices that they have not yet tested. The empowerment that comes with accessibility is immense. Within our own county, this accessibility is being fueled by the efforts of the Lending Library and by the DCIU as a whole. Equipped with the right technology, we can begin to see that students with disabilities and conditions are valuable; they are a force to be reckoned with.

Special thanks to, first and foremost, Jason Gonzalez, Nora Connell, and Marisa Giannini, for taking hours out of their workday to show me around the Lending Library and teach me all about it. You guys do incredible work, and hundreds of students in our county can access school now thanks to you.

Thanks as well to the Audiology Department at DCIU, who have touched my life personally by providing me with free hearing equipment for use in my two-teacher class. I use that equipment every day and could not be more grateful.

Finally, a big thank you to Mrs. Rudisill, who helped orchestrate my visit to DCIU! I couldn’t have done this without you.