The Wild, Wilful, and Wonderful Winsors

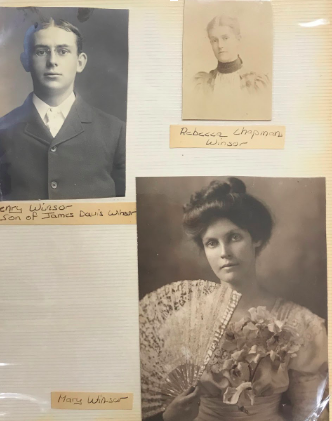

Mary, Henry, and Rebecca Winsor

October 3, 2019

The newly renovated Radnor Memorial Library, located in the heart of Wayne, is a cultural center for our community, supporting events such as storytime, interactive music performances, puppet shows, and a variety of camps. The exact location of these events –The Winsor Room –is tucked away in the basement of the Library, where the rich history of the people it was named after goes somewhat unappreciated. The Winsor Room, for which funds were bestowed to the township in 1962, is named after two of the most ambitious, generous, and sometimes mischievous women to ever live on the Main Line.

Marry, Rebecca, and Ellen Winsor were born in Haverford during the late 19th century into a wealthy Quaker family in the steam shipping industry. They were educated in Philadelphia at the Galbraith School in Delancey Place. On account of their family’s good fortune, the Winsor children were very well-traveled, though Mary would always complain that they were too chaperoned, and, during their travels, they rarely escaped tedious tours of churches and graveyards. At one point Mary announced that “the greatest curse in the world was to be born a girl in a genteel family.” Mary came the closest to attaining a bachelor’s degree, through taking various classes at Bryn Mawr College, but did not pursue it further. Despite a lack of secondary education, all the sisters were very well-read. It was a Windsor family practice to discuss what they had learned from their readings, and they were encouraged to “say what they wished and discuss anything they chose,” according to Ellen.

Mary, the oldest of the sisters, paved the way for the others’ activist roles within the suffrage movement. In 1910, she founded the Pennsylvania Limited Equal Suffrage League and was a very active member of the National Women’s Party. She was also instrumental in organizing the first meeting focused on legalizing birth control in Pennsylvania. Influenced by her travels to London and observations of the more militant and violent suffrage movement in Britain, Mary would never shy away from conflict. Like many other suffragettes of her day, in 1917, she and her two sisters were arrested while picketing at the White House. After refusing to pay the fine, she was sentenced to sixty days at Occoquan Workhouse in Lorton Virginia, notorious for its mistreatment of suffragettes. Ellen and Rebecca were both bailed out of jail by their brother, who described the act as the “damndest foolish thing” he had ever done. Mary, however, refused to leave, and instead chose to endure the harsh treatment for the full two months, thirteen days of which she spent in solitary confinement. Two more times in the decade, Mary was imprisoned for her activism. She was released both times after a hunger strike, during which she withstood several force-feedings. After the passage of the 19th Amendment, little is known about Mary’s life. She got married and had children, and acted more as an observer for the years to come, during which her two younger sisters took to the stage of activism on the Main Line.

At the root of their activism was their self-described position as anarchists — every person should have the freedom to do what they pleased, and it was their duty to become involved in any cause where they felt that someone’s freedom was being undermined. Despite their commitment to the suffrage movement, after 1920 neither sister was ever seen at a polling place. Instead, they rejected their government altogether, though they never shied away from discussing politics. As written in an obituary, “McCarthy was despised, so were the communists.” They expressed their freedom to control their own lives by refusing vaccines; wanting to avoid all of the chemicals. They were so committed to this practice that they gave up their European travels when immunizations were required to enter the continent.

One of Ellen and Rebecca’s most publicized acts of rebellion, which led to their arrests and spurred numerous local articles, was collecting signatures at the Metropolitan Opera House calling on President Harding to grant amnesty to political prisoners. At their hearing, instead of walking in with shame, they “arrived in a big automobile and were fashionably dressed and apparently considered the proceedings a great lark,” according to an article clipping from 1922. From the testimony of Sergeant McCort at the sisters’ hearing, after they refused to stop collecting signatures upon request and their arrest was ordered, “Miss Winsor got excited and called in a loud voice that they were American citizens. They were boisterous and loud and caused a disturbance in the lobby.” David Wilkin also testified that Ellen “resisted arrest and dragged her feet like a child as she was being taken.” Despite their resistance, they boasted that the incident was “no new experience for them.” From Ellen and Rebecca’s perspective, possibly adding to the amusement of the trial, they were each held under a one thousand dollar bail. In the end they were charged on three accounts, disorderly conduct, breach of peace and inciting to riot, all in the name of fighting what they thought to be the overarching control of their government.

Their belief in everyone’s personal freedom was expressed in all of their work. For years, Ellen worked for the NAACP and was acquainted with some of the biggest names of the Civil Rights movement of the Reconstruction Era, such as Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. DuBois. She quit in 1917 when the organization chose to support the war effort – her belief in pacifism was too strong to be a part of any organization that supported the war.

The Winsors’ strong passion for pacifism was no doubt a product of their Quaker upbringing, but their relationship with religion in their adult lives was a complex one. Despite their appreciation for many Quaker ideals, they denounced any form of organized religion, claiming that it leads to “intolerance and persecution” and infringed on an individual’s autonomy. As part of the national Tax Refusal Committee of Pacifists, multiple times they refused to pay taxes that would fund the military and went as far as to write a book, Land, Labor and Wealth, on the principles of taxation.

As strict vegetarians, they extended their ideas about pacifism to their diets, and Rebecca even tried her hand at satire in a letter to the editor: “Lobsters throw a dinner party.” With her typical outspoken attitude, she asked readers “have you ever considered how you look to the pure eyes and mind of a vegetarian when you are eating corpses and thus making a morgue of your stomach?” The Winsors’ meat-free household never stopped them from throwing parties with beautiful arrangements of food, nor did it deter guests. In a published biographical article, a friend of the sisters described “A party at the Winsors’ [as] fun. Arriving one might wonder indeed at the miscellany of folk, young, old, men and women, white and black, socialite, teacher, musician, housewife… and everyone would leave wondering how the time had gone so fast.”

Going through the stack of articles donated to the Radnor Historical Society, written by their friends morning the loss of two of the most impactful women on the mainline, one can only imagine how these women managed to touch so many people’s lives around them. In her book, We Scrapples – Philadelphia’s Main Line as it Really Was, Molly Tenbroeck dedicates an entire chapter to the Windsors. The firsthand account gives a window into what truly unique characters they were. The book recounts their lively parties, arrests, and complete disregard for social custom: “[Ellen] lives gaily unhindered by custom. ‘What will people say?’ means absolutely nothing to Ellen and Rebecca.”

Henry Winsor and daughter Bibbi Hotaling, two descendants of the sisters’ brother, James Winsor Jr., are still living near Radnor, and were kind enough to share their memories and knowledge of their aunts. Bibbi, though she never met them, had a great sense of their free spirits through the information she acquired through her family. Mr. Winsor, who knew them into his young adulthood, described them with fond remembrance. And, although he was less than thrilled to visit their house at Thanksgiving, he remembers that their eyes “were absolutely just dancing in their heads” and they were “very present whatever the conversation happened to be.” He told stories of them gardening in the nude without a care in the world, and more or less being considered the wild aunts of the family. Though they sometimes had to put up with their antics, the names of Mary, Rebecca and Ellen will live on through the types of family conversations that they so cherished throughout their lives.

They showed their love for their community not only through sharing friendship but by sharing music. Ellen and Rebecca were the co-founders of the Tri-County Concerts Association, and held three to five concerts a year with free admission, starting in 1942 in the building that was Radnor High School at the time. With each concert, they intended to “bring the spiritual peace and the beauty of music in the lives of our fellow-citizens who were living under the shadow of war,” according to one of their first programs. The Concert Association is still a nonprofit that continues to share music, with the goal of “encouraging appreciation and inspiration” of and by music. Rebecca and Ellen received no personal income for their work –they worked because they thought “great music makes life harmonious,” according to Rebecca.

Needless to say, the community suffered a loss in 1959, when Ellen and Rebecca died within an hour of each other, one after a long illness, and the other reportedly from shock, three years after their older sister Mary. To what we can only assume to be her liking, on Ellen’s death certificate her official occupation was listed as a “Professional Agitator.” Their home, named Spring House (they had a history of naming their homes, previously living in “The Monster” and “The White Elephant”) was donated to the township, with the wish of it becoming a cultural center for the community. After a battle between various nonprofit organizations in the area looking to acquire the space, the township chose to sell the house and put the profits towards another cultural center of the town: the library. To honor their generous donation, the space we know as the Winsor Room in the basement of the Radnor Memorial Library was named in their memory. So, next time you have the pleasure of entering our local library, be reminded of the history behind this community center and remember these three wild, willful, and wonderful women who brought so much joy and excitement to the Main Line decades ago.