101 Years After The Amritsar Massacre: A Possible Seed of Growth for the UK and their Past

April 16, 2020

As the coronavirus sears across the world, continuously slowing down the pace of life, some of us are fortunate to have the time and resources to reflect on, healthcare systems, racial and socioeconomic disparities, and history in general. Ironically, this pandemic has improved human solidarity, empathy, reflection, and exploration. Every day we hear stories of incredible yet ordinary people who have sacrificed their jobs, personal freedoms, and lives to save strangers they will never truly know. As we collectively venture into this time of uncertainty as a society, it is crucial to never forget our history and the loved ones who fight for our security, independence, and health. As bored as we all are at home, it is important we look back into the history books to commemorate and mourn our past. Our world has seemingly come together in a way that is almost unimaginable: through a deadly virus. And today, amidst this chaotic and reflective time, I’d like to commemorate a day in history when 379 innocent people were brutally shot dead in the Amritsar Massacre in India on April 13th, 1919.

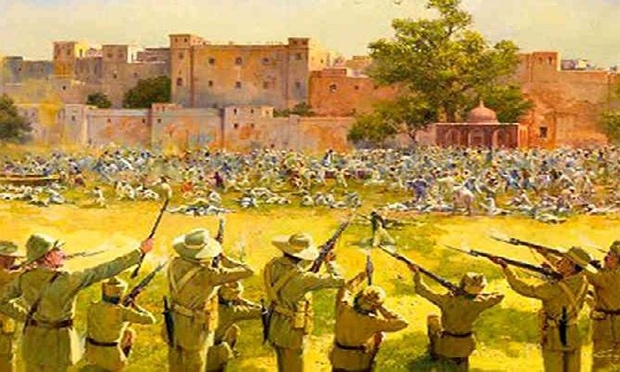

Monday marked an important festival called Baisakhi in India, marking the solar new year and harvesting season. On this day, 101 years ago, a British general marched through a peaceful gathering in a park and made an order to shoot down unarmed Indian men, women, and children. Within 10 minutes, hundreds of innocent lives were taken. There was no warning, no dialogue, no way out for the thousands of people gathered – defenseless – the General ordered his troops to fire at their chests, faces, and wombs. There was panic in this park, with nowhere to go, because the only exit was blocked by the firing soldiers. Many of these men, women, and children jumped into a well that was situated at the center of this garden. The ten minutes of this murderous tyranny continued through the shrieks and bloodshed until there were no more bullets to be fired.

The Amritsar massacre serves as the fundamental turning point in India’s fight for freedom from Britain- changing Indians’ view of the Raj (the era of British rule running from 1757 to 1947). During the years prior to the Massacre, Indians had contributed massively to the victory of World War I in manpower, resources, and money, and as a result were confident that the British would reward them with more political autonomy- similar to the supremacy status the British had given the caucasion people of Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Indians’ hopes were especially raised in the 1918 Balfour Declaration that promised the Jewish a homeland in Palestine. Little did they know the British war cabinet had secretly concluded that India would not fall under self-rule for another 500 years to come.

After the end of the victorious war, instead of greater liberty or eased regulations, the British responded with severe crack-downs of search and arrest without warrants throughout India. Na dalil, na vakil, na appeal, the Indians called it- no argument, no lawyer, no appeal. Anger and discontent was widespread amongst Indians, especially in the Punjab region. In early April, as an act to ease violent tension, Gandhi called for a one-day general strike throughout the nation.

However on April 10th, on his way to Amritsar, Gandhi was arrested and banished from the city. In Amritsar, the news sparked violent protests, in which soldiers fired upon civilians- killing 15 people. Enraged by the acts committed by the British, the Indians continued to protest, resulting in the looting and burning of buildings as well as the killing of five British civilians.

On the afternoon of April 13, a crowd of thousands gathered at the heart of Amritsar, in Jallianwala Bagh park, a popular spot for public gatherings, enclosed by high walls and only containing one exit. Families, including children and women, congregated to discuss politics but mostly to celebrate Baisakhi. Minutes into the event, without any warning, troops entered through the only point of entry into the park. Within seconds, General Dyer ordered soldiers to fire at the gathering for 10 minutes straight; only stopping because they had run out of ammunition. 10 minutes passed and 337 men, 41 women, and a seven-week- old baby had been killed, with another 1,500 injured (the Indians claim that more than 1,000 people were killed). The General gave no warning, no announcement for these gatherers to leave, he just ordered his troops to start shooting at them until they exhausted all ammunition.

101 years later, the Britishers and Indians continue to grow further apart after the continued recalls of such barbarity. In 1997 the Queen became the first British monarch to visit the site of the massacre, but did not apologize for the actions of the British; she simply signed the visitor’s book at the memorial. In 2013, David Cameron became the first prime minister of Britain to visit the memorial. While he admitted to the disgraceful event he also felt he could not “reach back into history” to apologize for British actions.

Why today, you wonder? It’s been 101 years, and the number one has a symbolic meaning to Indians since the beginning of time. In Indian culture, the additional ‘one’ has a symbolic meaning. My mother always adds a dollar to any cash gift, symbolizing luck. One dollar is said to be all that is needed for a seed to grow; it is to be invested or given in charity, perpetuating the act of paying forward.

As we look back, for the 101st year, on the tragic Amritsar Massacre, Britain must plant a seed for growth. Today, Indians are reaching back into history and demanding an apology. Hopefully, the extra year after a century of Britain’s unapologetic behavior will spark an act of kindness and acceptance on Britain’s behalf, potentially planting a new seed for the future of Indian-British relations.

Rachel Ebby-Rosin • May 6, 2020 at 6:04 pm

Thank you so much for writing this article. I am embarrassed to admit that before reading your piece, I knew nothing about this important yet horrific event.

Deepti Thapar • Apr 21, 2020 at 10:33 pm

Great job Anika!!

You’ve very accurately captured an often overlooked historical event in an engaging, well-written article. Keep up the good work.