Post-election Anxiety

https://www.google.com/search?sxsrf=ALeKk02qkY5YWcgGmx3SE4wgyi9bzxXJhQ:1605016346218&source=hp&ei=GpuqX6yUCuLF_QbX97XgDw&q=2020+election+map&oq=20&gs_lcp=CgZwc3ktYWIQAxgAMgcIIxDJAxAnMgQIIxAnMgQIIxAnMgoIABCxAxCDARBDMgoIABCxAxCDARBDMgcIABCxAxBDMgoIABCxAxCDARBDMgQIABBDMgQIABBDMggIABCxAxCDAVDFCViLCmDbD2gAcAB4AIABTogBkwGSAQEymAEAoAEBqgEHZ3dzLXdpeg&sclient=psy-ab&safe=active

November 12, 2020

A pile of assignments. An oncoming wave of tests. A breakup. A mediocre GPA. Each of us can associate with the stress and sleep-loss of one of these mountains. Right now, however, this mountain has a fifth peak: the election and the looming fallout.

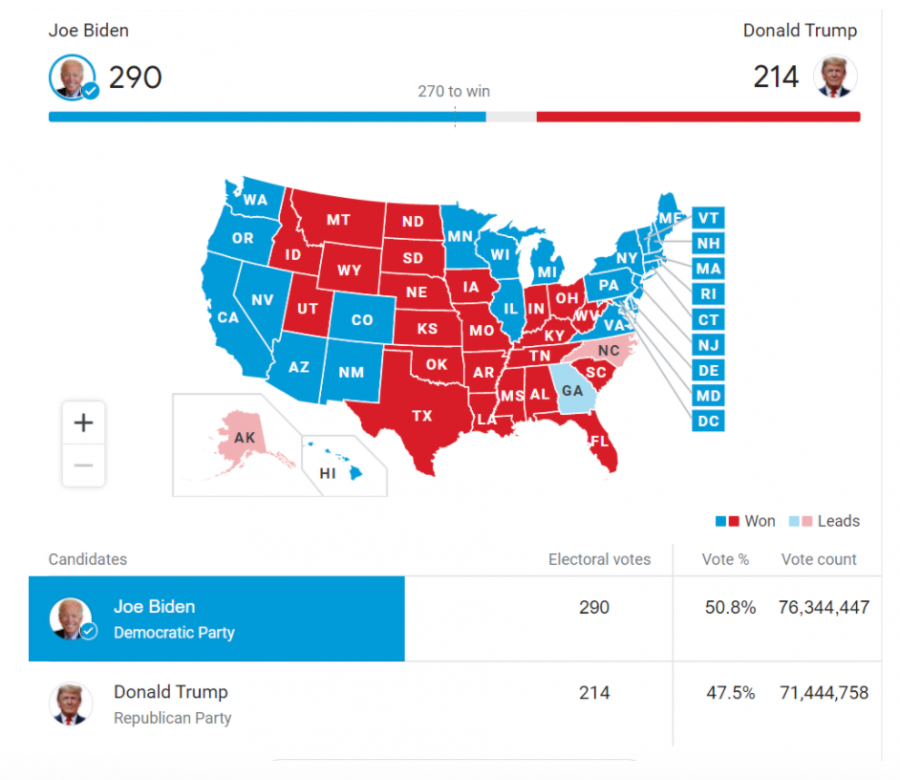

Usually, the post-election week is relatively calm. After all, in the previous 58 presidential elections, the loser has (almost) always conceded the race, and in the case of an incumbent losing, the incumbent has (almost) always committed to a peaceful transfer of power. After all, isn’t that supposed to be normal for a democracy? But this year is different. A president has never before been unclear about his commitment to a peaceful transfer of power. These questions are already causing a lot of stress: What if the president refuses to concede? Will there be violence? Now that Joe Biden has been elected president, these questions race to the top of concerns.

According to an American Psychological Association study, nearly 70% of Americans feel that the current election is a significant source of stress. By contrast, in 2016, that percentage was 52%. And it is not just the election that’s causing increasing anxiety. The same study also stated that 77% of Americans are worried about the future of this country. “This has been a year unlike any other in living memory. Not only are we in the midst of a global pandemic that has killed more than 200,000 Americans, but we are also facing increasing division and hostility in the presidential election,” CEO of the APA Arthur C. Evans, Jr., Ph.D., says, regarding the circumstances. “Add to that racial turmoil in our cities, the unsteady economy and climate change that has fueled widespread wildfires and other natural disasters. The result is an accumulation of stressors that are taking a physical and emotional toll on Americans.”

What Dr. Evans said is absolutely right. The campaign ad messaging seen this year had created the impression of many existential threats — our democracy’s impending doom, coronavirus, and civil war. Some of these threats have already taken a toll. For example, the coronavirus has not only infected millions and killed hundreds of thousands, exhausting our supply of ventilators, it has also caused millions of Americans to lose their jobs. Virtually no person in America, and indeed in the entire world, has been left unaffected by the pandemic, even if they avoid infection. Schools are going virtual or hybrid. Businesses are closing — many permanently. Events are canceled, or worse, they become harbors for the coronavirus. Members of extended families have been forced to separate for over a year. Depression diagnoses have increased dramatically, and counseling services are booked full.

To complete this scenario, the wave of protests in support of Black lives and against police brutality and systemic racism — triggered by the horrific deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery — has been yet another source of stress, albeit for different reasons. Some remain anxious about the prospect of rioting and looting that might happen in their communities, even boarding up stores and homes, while others are apprehensive about becoming the next victim of police brutality. For example, despite the protests, it still didn’t stop Rayshard Brooks from being shot and killed, nor did it prevent Jacob Blake from being shot seven times in the back. Nor did it stop a variety of businesses from being looted and their windows smashed. Either way, there’s unrest — and plenty of stress.

All of this has elevated the stakes to a fever pitch. Parents, students, business owners, politicians, and other members of the community are anticipating violent protests, destruction of property, intimidation, and even acts of vigilantism. Such worries are common in times of unrest. This is reminiscent of the numerous periods of turbulence this nation has experienced, from the Civil War, to the massacre in and destruction of Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921, to the turmoil in 1968 in which many civil rights icons were shot and killed, such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, and more.

In the meantime, there is at least a sign of change. With a new president about to go into office on January 20, 2021, comes new plans and a glimmer of hope, one that hopefully tackles all the aforementioned problems, and more. And his rhetoric doesn’t sound divisive — at least so far. Rather, it sounds more unifying. “I pledge to be a president who seeks not to divide, but to unify — who doesn’t see red and blue states, but the United States,” he said during his victory speech on Saturday, “and who will work with all my heart to win the confidence of the whole people.”

Usually, as students, our anxiety is concentrated on grades or SAT scores. The election, too, can be seen in a similar light: whether one’s preferred candidate wins or not. Normally, Election Day can be stressful, but not crushingly anxiety-producing. After all, we vote early or on that day, hear preliminary results at night, and maybe hear the final results the next day or a few days later.

The unique thing about this particular election is how this nation is already in turmoil and division, exacerbated by the pandemic. Such things, as seen so far, makes one worry about “what the other side might do.” In the instance of loss, one ponders whether they will stoke violence, contest the election, or further erode confidence in our social institutions, maybe even slip into authoritarianism. Despite all this, there always is a chance to turn things around for the better. We voted; now let’s wait for the count, anxiously and patiently. And who knows? Maybe this will be an opportunity to reform our democracy to make it even more in favor of the people.

Just look at the track records: The Gilded Age (and the concentration of wealth) led to reforms like women’s suffrage, direct elections for the Senate, and more. The Civil Rights Movement ensured that the 14th and 15th Amendments are held true to form, and the Vietnam War helped lower the voting age to 18. Even after the Civil War, one of the most divisive times in American history, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were passed, with the latter expanding voting rights. In many cases, anxiety about democracy has led to a swath of reforms that bettered our government. In every dark time, we’ve rebounded.

Will this happen again? Maybe, maybe not. Hopefully, it will. The latter is certain, for sure. The election of a new president who currently does not show any sign of habitually breaking norms can make that happen a bit quicker.