“Ew, what is this?”: Anti-Asian racism

March 24, 2021

“Ew, what is this?” a student remarked at my food during a middle school lunch. The food was dumplings.

My heart rate accelerated like a race car, trying to process that comment. My jaws dropped, not knowing what to say. Since when was calling food disgusting a thing? I thought. Should I just tell them that these are just dumplings?

If I saw your food on the cafeteria table and called it disgusting, how would you feel? Whatever you would have felt, I was feeling at that moment.

The school rules forbade sharing food. You won’t be eating my food anyway, so why bother calling it disgusting?

This can happen anywhere — even in a four-year No Place for Hate school.

Attacks against Asian-American people surged in number since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. Some of the many victims include a 91-year-old man, a 60-year-old man, and a 55-year-old woman. One assailant assaulted and robbed a 64-year-old woman in February. An 84-year-old man named Vicha Ratanapakdee died after someone pushed him to the ground. A mass shooter in Georgia killed eight people, six of them Asian women. The surge in hate crimes has shocked many Asian-Americans to the core.

Honestly, I never thought this could happen. After all, wasn’t I supposed to be a virtuoso musician? Wasn’t I supposed to be a stellar student and get straight-A’s? Wasn’t I supposed to adhere to the norm? Shouldn’t I be successful?

To make matters worse, the press covers these attacks only sparingly and inadequately. The call to address this issue frequently pops up on my social media feed. “@nytimes @abcnews @latimes @wsj @bbcnews @abcnews why is no one reporting about this?” one post said. Another wrote, “The media needs to be held accountable. Call these ‘incidents’ what they are: hate crimes against Asian-Americans.” Because of the lack of media exposure, many people do not realize what is happening, much less its extent. Even some journalists are in the dark.

Much of this ignorance also stems from the lack of education about racism and its history.

Though we learned in school some history of racism in America, one part of it often goes missing — anti-Asian racism. History textbooks often teach us about racism directed towards Black people. Still, textbooks only scantly exhibit or completely leave out the experiences of other minorities, even though they have faced their own decades of struggle.

The inadequate education on racism, especially towards non-Black people of color, explains the prevalence, acceptance, and even encouragement of racism. And such education, or lack thereof, profoundly affects how society moves forward. George Orwell once wrote in 1984, “Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.”

The history of racism and prejudice is repeating itself.

So, some history of anti-Asian racism:

It was 1849. The California Gold Rush was in full swing, and many people, including Chinese immigrants, were trying their luck. They were motivated not just by gold but also new economic opportunities. At that time, China was reeling from debt and despair after the Opium Wars with Great Britain. China lost these wars, and Britain coercively forced China to sign treaties giving up much of its sovereignty and open up its trading ports. China dubbed them “unequal treaties” because of their inequitable nature. This hardship in China drove many immigrants to seek a better life in the US — much like how the Irish Potato Famine drew Irish immigrants to the US.

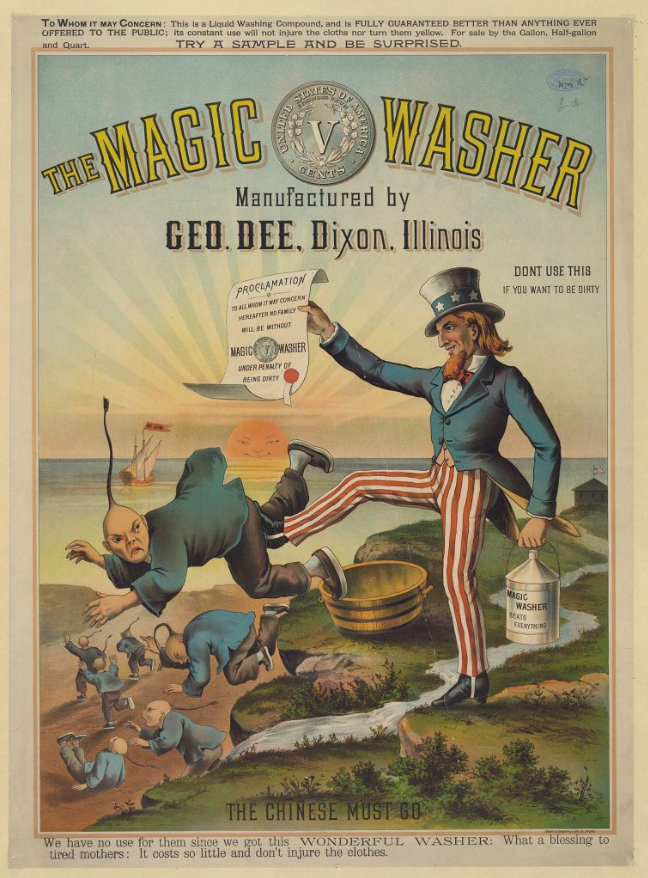

Ultimately, the California Gold Rush ended, but Chinese immigrants still settled in California, taking on jobs in agriculture, factories, and railroad building, earning money for their families living with them and back home. However, along with Chinese immigrants came anti-Chinese sentiment and racism — exacerbated when job competition arose between Chinese people and other people in America. White citizens developed a sentiment of “yellow peril” — basically fear of the Chinese “taking over” and “degrading American society.” People also believed that they were “taking their jobs,” a common anti-immigration sentiment today.

And so the US passed into law one of the first immigration bans — the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This law prohibited Chinese immigrants from entering the US unless they were not laborers, that is, not seeking jobs. Very few people qualified under that category, so the act banned virtually all Chinese immigration. The prejudice did not stop there. The Scott Act of 1888 prevented people in the US who traveled to China from coming back, and in 1902, the Chinese Exclusion Act was renewed indefinitely. It would only be repealed in 1943 when China allied with the US in World War II.

Chinatowns were born, in large part, because of racism and racist policies. Initially, Chinese immigrants to the US settled much like other immigrants did — establishing businesses, settlements, and towns. Though Chinese immigrants were not the only ones discriminated against, they stood out in that people considered them “unassimilable” and thought that “they can never become citizens.” (Other immigrants, such as the Irish, the Germans, and the Italians were able to integrate.) Such sentiment and the growing number of anti-Chinese hate attacks forced Chinese-Americans to self-segregate in communities dubbed “Chinatowns.”

This unenforced segregation also brought about a few benefits. Remember the Chinese Exclusion Act? In addition to immigrants who weren’t looking for jobs, merchants were also exempt. Chinatowns became thriving places of commerce as businesses sprung up and grew. They also became tourist centers; people felt more “safe” to visit Chinatowns as the yellow peril fervor died down after the Chinese Exclusion Act passed in Congress. Other East Asian minorities also settled in Chinatowns.

The Chinese were not the only ones who established separate communities, and immigration bans did not just target them. Japanese immigrants also came to the US for opportunities there — motivated especially after Matthew Perry showed off his fleet to Japan and revealed the US’ technological and economic might. Japanese immigrants came to the US in droves, and established Japantowns.

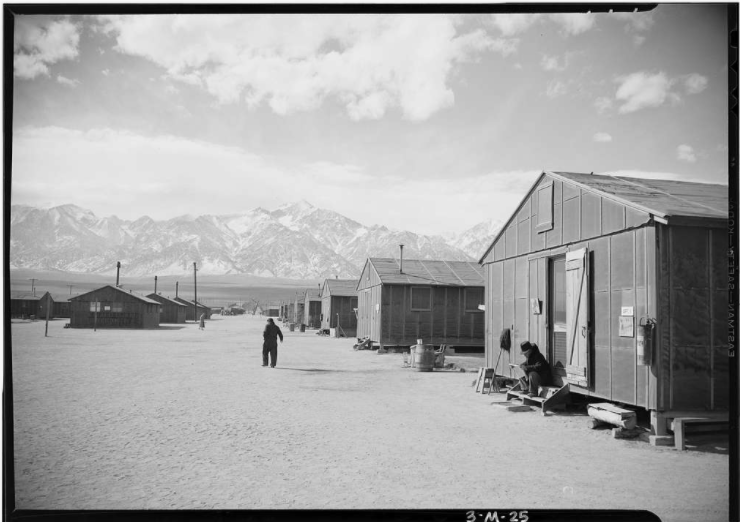

Japanese immigrants faced similar challenges to Chinese immigrants, including Chinese Exclusion Act-like laws. But they would soon fare much worse. In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which rounded up Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast and sent them to internment camps.

Lt. General John DeWitt sought to prevent a repeat of Pearl Harbor by watching the civilian population closely for “sabotage,” which motivated FDR’s executive order. And by “civilian population,” he meant the Japanese, but also the Italians and Germans. The latter nationalities, however, were not rounded up because they were considered “white.” Fears of espionage and accusations of treason ran amok, even though two-thirds of Japanese-Americans marked for internment were native-born American citizens!

Though anti-Japanese racism existed ever since the first Japanese immigrated to the US, Pearl Harbor gave Americans an excuse to show this racism in broad daylight, just like COVID-19 and anti-Asian racism today.

Internment was devastating. Not only were Japanese people taken from their homes against their will, but they also lost their livelihoods upon release. Japanese-Americans “found their homes or farms ill-cared-for, overgrown with weeds, badly tended or destroyed [while] one person reported finding strangers living in his former home,” the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians reported. The total damage to their homes exceeded six billion dollars, and Japanese-Americans were feeling its impact long after the war ended.

The US government finally paid reparations to Japanese-Americans after 43 years, doling out $20,000 to every descendant of those interned. However, many Japanese-Americans valued the recognition of the crime as more important than the monetary compensation, though it was still not enough for some. As President Ronald Reagan stated, “No payment can make up for those lost years, so what is most important in this bill has less to do with property than with honor for here we admit a wrong.”

So how did Asians really become a model minority of textbook swimmers? What if I told you that our Cold War rivals, the Soviet Union, played a role in crafting this myth? Well, it’s true.

Consider this: you are a Soviet propagandist in the 1950s and 1960s wanting to convince citizens of your country and others to join your side. What better way to do so, than to demonize your enemies, the United States, and what better way to do so than to paint the US as a hypocritical country? After all, the US is supposed to be a place of freedom, justice, liberty, and opportunity for all, yet it sent Japanese-Americans to internment camps not that long ago, Jim Crow segregation is alive and well, and racial discrimination persists.

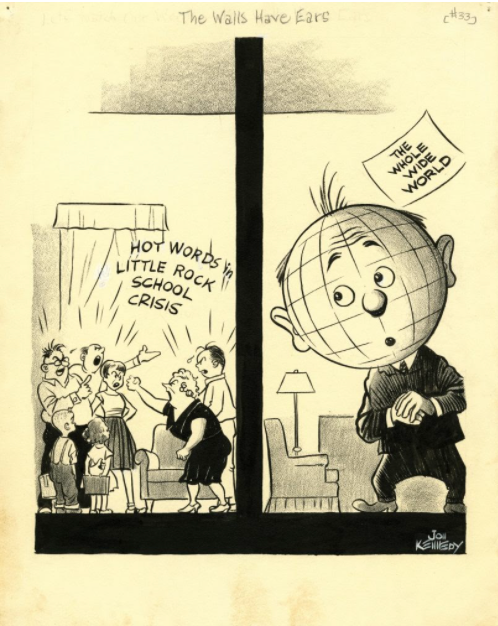

In 1957, nine Black students attempted to enter Central High School, despite Governor Faubus’ attempts to block them from entering. We all know how it ended: the students eventually got in with the help of an armed escort courtesy of President Eisenhower. However, foreign countries, especially the Soviet Union, seized upon this story to discredit American democracy.

The Little Rock crisis presented an opportunity for the Soviets that they did not pass. The Soviets ran sensational stories revolving around this event, using it as proof that America is hypocritical with its ideals. Komsomolskaya Pravda, a Soviet newspaper, published a story titled, “Troops Advance Against Children!” and accompanied it with photos from Little Rock, including, “a photo of the [Arkansas] national guard unit in Little Rock directing a Negro girl away from the high school.” Another newspaper, Izvestia, said, “Right now, behind the facade of the so-called ‘American democracy,’ a tragedy is unfolding which cannot but arouse ire and indignation in the heart of every honest man.” This did not look good for the United States, so much so that Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., the UN ambassador to the US, wrote to President Eisenhower, saying, “More than two-thirds of the world is non-white, and the reactions of the representatives are easy to see.”

In addition to international pressure, America’s fear of communism spreading contributed to the loosening of unfair policies against Japanese Americans. Eight years before the Little Rock Nine event, the Communist side won the civil war in China and America was afraid of a “domino effect” where communism spread like wildfire in East Asia. To convince countries to reject communism, the US had to position itself as better than it; however, America’s perceived hypocrisy made that difficult.

The US aligned with Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea as allies to contain the communist spread. It would not make sense to ally with a country but discriminate against its population, so to avoid alienating its allies, the US decided to kill two birds with one stone. It relaxed its racial discrimination laws and overall anti-Asian racism for a PR makeover. As Ellen Wu, Professor of History at Indiana University writes in her book The Color of Success, “The United States’ battles against fascism and then Communism meant that Asiatic Exclusion, like Jim Crow, was no longer tenable. Seeking global legitimacy, Americans moved to undo the legal framework and social practices that relegated Asians outside the bounds of the nation.”

America touted stories of Asian American success, and not only repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act, but also passed the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965. Wu also writes in her book, “The conceit of the meritorious Chinatown family constituted a fundamental precondition for the emergence of Chinese Americans as definitively not-black model minorities in the mid-1960s. As they did with Japanese Americans, social commentators and policymakers depicted Chinese and African American households and communities as absolutely antipodal despite the congruence of their inner-city surroundings.” In that, America was painting an image of Asian-Americans succeeding despite previous racial discrimination, “proving” that people of color can succeed — had they just work hard enough. This narrative then became a stereotype for all Asian-Americans. The model minority myth was born.

These policy changes improved the image of the US abroad to make its appeal credible, but it had another effect — putting other minorities down. It was about this time when the Civil Rights Movement gained traction, as Brown v. Board of Education was just decided, legally barring school segregation. Asian-Americans’ newfound acceptance sent a message to Black Americans. Why are you complaining about ‘civil rights’ when you see them succeeding? Why don’t you just follow their example and live like them?

Ignore the fact that we enslaved your ancestors for a quarter of a millennium; ignore the fact that we leased your ancestors out as convicts after they were freed from slavery; ignore the Jim Crow laws and redlining; ignore the weekly lynchings; ignore everything, pretend it never happened and just work hard and be like them, it said.

Despite the extent of anti-Asian racism, it never reached the levels of two hundred and fifty years of chattel slavery, nor convict leasing after that, nor Jim Crow segregation, nor redlining, nor weekly lynchings, nor dilapidated communities caused by the latter three. The model minority myth served as an American PR stunt to improve their international reputation, while simultaneously suppressing the Civil Rights Movement. Ultimately, it divided people of color amongst themselves to prevent a full-on challenge to racism and white supremacy.

But wasn’t this new reputation as a model minority supposed to be good for Asians, and people overall?

The model minority myth came out of convenience. But forget that for a second and think about the actual content of this stereotype. Asians are musical prodigies. Asians are like calculators. Asians are your go-to for any sort of science. Asians are hard-working and very self-disciplined. Asians are straight-A students. Asians routinely make it to the top colleges. These may sound good to you. But what else do these stereotypes mean?

First, it means that Asians like me shouldn’t need help. After all, if they’re Asian, they should make it through by themselves. Try to imagine spending an entire school year not asking any teacher for help. All of us need help sometimes, Asians included. And what do you do when you don’t know something or are struggling with something? Ask for help. Talk about it. And help someone when they come to you for it. But because of this myth, people expect Asian students to make it by themselves, and thus help Asians in need less. It takes a toll on our mental health, too, as Asians hesitate to ask for help. Asians already seek mental health treatment at only one-thirds the rate of whites. Why would they — given the “figure it out” mentality?

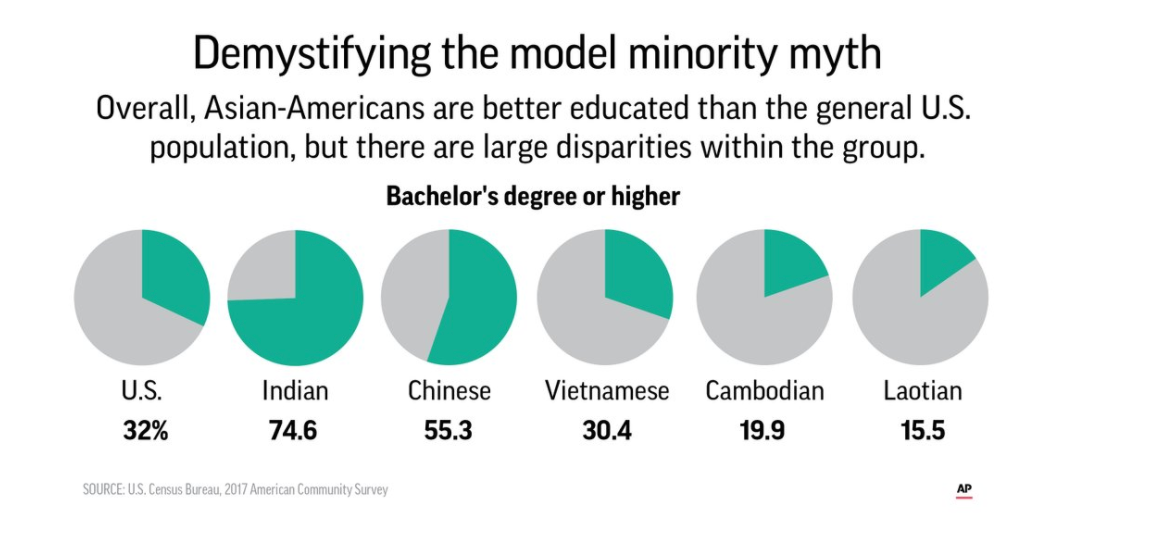

Second, notice that I said “Asians are x, y, and z.” Not Chinese-Americans. Not Indian-Americans. Not Vietnamese-Americans. Asians. 48 countries exist and 4.46 billion people live in Asia. Imagine trying to take 4.46 billion people living in 48 countries and labeling it all under the umbrella term Asian. Some Asians don’t celebrate Lunar New Year. Some Asians don’t eat with chopsticks. And think about the religions Asians practice — Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Shinto, Sikhism, and yes, Judaism and Christianity, there are countless to name. And don’t get me started on all the cultural traditions — there are too many to name. Simply saying Chinese Americans or Japanese Americans doesn’t encompass everyone.

But, in simply using the world “Asian,” other problems arise. For example, the poverty rates of Asian Americans are often lumped together. The Burmese-American poverty rate is as high as 39%, in contrast to the 7% Filipino-Americans poverty rate. Pay gaps exist too. For every $1 earned by a white man, an Indian woman makes as high as $1.21, but a Burmese woman only makes two quarters. Is it really that some Asians just aren’t as successful as others, or is there something else going on?

Third, and most importantly, the model minority myth pretends that anti-Asian racism does not exist. Where do you see Asians depicted negatively in that myth? Honestly, I felt backstabbed when I heard about the recent attacks on Asians. I worked so hard…for this, I thought to myself. The model minority myth hides the other forms of anti-Asian racism, too. Asians rarely make it to leadership positions despite this myth, making up less than three percent of Fortune 500 leadership boards. Were you ever asked where you’re really from? I can tell you I was born in Indianapolis, IN, and my parents came from China. But it is the “really” part that sticks — it is the “really” part that seeks to keep us as perpetual foreigners.

And believe it or not, the model minority myth is racist towards Asians as well. In the words of a former classmate of mine, “I’ve heard over and over again, ‘You’re Indian, shouldn’t you be smart?’ and people constantly asking me for answers to questions I don’t know. If I tell them I don’t know the answer, they get mad and call me dumb because I’m Indian and I should know the answer to every frickin’ thing.” If you label one group with “good” stereotypes, then you simultaneously shame those who don’t conform to it.

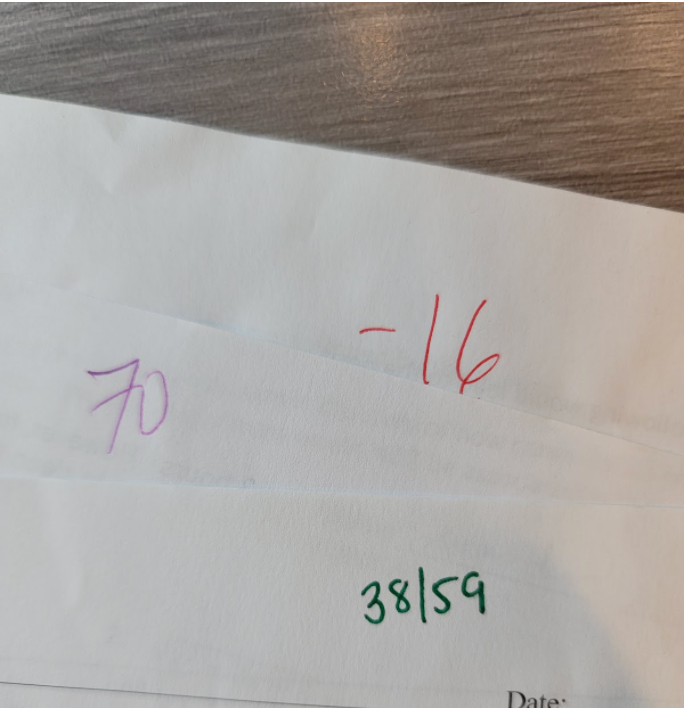

This prejudice does not have to be verbal, either. According to the model minority myth, I should have straight A’s all the time and a GPA of at least 4. Not only that, I ought to fail zero tests. Instead, my GPA was a 3.95 in the first semester of my freshman year, falling as low as 3.33 in middle school. I even had a C+ in math at one point — yes, math! And I even failed tests. Say what you want about how grades should not define our worth, but they did for me last year. And there was no one time where I felt more worthless than the time I got two F’s on two math quizzes, back to back.

“I wasn’t expecting these grades from someone like you.”

It was the class after quiz day. My classmates and I were about to get our quizzes back. It was the first quiz for the second semester. I felt anxious waiting for the results — aren’t we always? It felt like a movie to me, a suspenseful scene. Then my quiz came.

“59%,” it displayed in bright ink. My first thought: is there anyone who’s gotten worse than me? Then my classmate sitting next to me got hers. (She’s white.) Her test score was somewhere in the C range (70-79%). I then sat up as straight as I could, searching for a grade lower than mine. Turns out there wasn’t a lower grade — mine was the lowest.

I sweated like I was in trouble. Back then, I hadn’t thought of telling myself, “Even Harvard students fail a test once.” I was fearful at being told, “I wasn’t expecting these grades from someone like you.” Or, “Why should I trust you helping us when you’ve got that?” So I told nobody and instinctively hid my tests in my binder. I almost felt like a criminal and even considered shredding that quiz as if it were evidence. And getting an F was horrifying enough if it were not for my Asian identity; I should have gotten an A, or a B+ at the lowest.

I earned a lower grade on my second quiz. “56%,” it shouted. I felt the same as I did when I got my first F, and all my same fears came back. So I again concealed my quiz again in my binder. But this time, the aforementioned classmate who sat next to me said, “Guess how low I got?” I correctly answered that she got an F along with me, and with that I became relieved. At least I’m not alone, I thought.

But that was only temporary. The ineffable feelings came back. Her score was higher than mine — fifty-nine compared to my fifty-six. I felt hopeless at that point. Repeating the class or dropping to a lower class seemed like the best choice for me, if “best” meant “embarrassing” as well. For an Asian-American to get not one, not two, but two consecutive F’s on a math quiz was almost unheard of. It felt like a crime for me to flunk a subject that demands the highest marks from me.

That’s only one way that racism manifests itself.

So what’s all the fuss about?

There are over 3,800 documented anti-Asian hate crimes — over nine a day. Just the documented ones.

Two in five Asians say people are expressing more and more racist views since the pandemic.

One in four Asian-American youths experienced racism since the start of the pandemic.

Anti-Asian hate crimes are NINETEEN times higher.

People were called “Chinese virus.”

Someone was assaulted.

Someone was robbed.

People were killed.

And yes, by the police, too.

And sadly, our last president, Donald Trump, only brought fuel.

Somehow we’re the “yellow peril” again. Somehow we’re “saboteurs” again.

“Those who don’t know history are destined to repeat it,” Edmund Burke once stated. History has repeated itself with the recent mass shooting that killed eight people, including six Asian women.

Even Radnor High School, a registered No Place for Hate school for four years, still has instances of anti-Asian racism and hate. A student here confided in me about an experience he had, saying, “I had just recently moved into [Virginia] and was hanging out with some new (Asian) friends (four people including me). We were out late, around 10 PM and a group of people (around eight) began yelling racial slurs at us and telling us to go back to our country. As they started to approach close, we got the feeling that things could get physical, so we all ran home as fast as we could. It was a very scary experience for me, especially because I was so young and the people yelling at us were much bigger.” Though this experience occurred in Virginia, it shows that even students at Radnor can still experience racism at one point.

He then adds, “At Radnor, [the racism is] a lot more hidden and maybe even unintentional,” saying that “It could be a subconscious thing of ‘that person looks different and acts different than me. He also has different traditions and ways of thinking than I do.’ But we notice it and it’s kind of frustrating because it’s so subtle that it’s not worth calling someone out for.”

Another student who lives in Indiana said something similar. “While we sometimes went across stores and outside places, random people would sometimes display their racial supremacy. They essentially were trying to tell us we didn’t belong and would act aggressively towards us,” he said. A third student there also told me, “It’s frightening to see innocent elders being harassed and harmed. I can only think about my own grandparents and hope that they are doing alright.”

Though it’s tempting to say “just ignore it,” or “move on, it’s not that bad,” these messages ring like earworms — heard so frequently that people of color believe the messages and internalize them. As I said before, such messages hurt — just one-thirds of Asians seek mental health treatment. And how can we move on, given the mass shooting that happened just recently?

Action steps

It’s uncomfortable to read this article. I know. But do you know what’s more so? Actually experiencing these things.

The pandemic gave America an excuse to be overt about their anti-Asian racism. From “Chinese virus” to people being harassed, assaulted, and murdered, anti-Asian racism has only gotten worse.

Thankfully, many people are opening their senses to this issue. Back to my social media feed, as I scroll through the stories, many people are sharing posts related to this issue. You can always join in, and take action. Here are some ways:

First, on the topic of the pandemic, say the name correctly. The virus is SARS-CoV-2. You could also call it the coronavirus — that’s colloquial. The disease it causes is COVID-19. DO NOT call it the “Chinese virus” — not only is that racist, but it’s the wrong name. Naming viruses after their origin location stigmatizes the people who live there, and viruses can spread much faster now.

Second, can you please just not scapegoat people for anything? Though the coronavirus first originated in China, that does not mean every Chinese person, and especially not every Asian, is somehow “responsible.” We’re not all bat-eaters, and we’re not all affiliated with the Chinese Communist Party, so STOP. In fact, what are you even trying to achieve?

A friend of mine, who is Asian, confided in me once, saying, “I was mainly just angry that the pandemic was triggering racism at all. It was truly disappointing to me that instead of coming together in a time like this, the world decided to turn on a specific race and blame it on them.” Another Asian friend echoed the former’s sentiment, saying, “I think that a way we could reduce racism against the Asian community is by simply not putting all the blame for a global pandemic on them.” After all, during last decade’s flu pandemic, we did not go around labeling fellow Americans as “having the flu,” or called it the “American virus,” so why should it be different now? Because the virus originated in China? Give me a break.

Third, spread the word. Raise awareness. Commit to justice. And please educate yourself. I stated before that the inadequate education on racism explains its prevalence, acceptance, and even encouragement, so isn’t the counter obvious? A student at Radnor, reflecting on not only the increased hate attacks on Asians but also on last year’s Black Lives Matter movement, said, “Educating people on this topic would be a good way to combat this racial tension that has formed over many years. Ultimately, we must stop hurting each other and begin spreading messages of peace, love, and positivity for everyone regardless of race, religion, color, creed, or sexual orientation.” It’s one thing to say it. It’s another to commit to it.

A way to spread messages of peace, love, and positivity is encouraging cultural appreciation and helping others! I understand the fear of “cancel culture” — but wanting to avoid “cancel culture” is no excuse to be racist, or sexist, or hold any other prejudice. And I also understand if you feel that this article is a bit harsh, but bear with me. It is possible to improve and learn from our mistakes, and I wish society would know that.

One time, my friend wrote to me about an experience she had in Indiana (she still lives there). She wrote, “I remember my family and I would always go to the Japanese Bon Odori festival every summer in Indianapolis and it was really such a great way for the Japanese community to feel at home here in Indiana. In the recent years, there have been many more non-Asians showing up in traditional kimonos and eating all the food and dancing with us. It was such a beautiful thing to see these people want to be included in just a small part of Japanese culture in a respectful way. I really wish we could reflect that one moment in time back into today’s society.”

“Acceptance” and “tolerance” sounds generic and leaves you pondering about how to be accepting and tolerant. There is a way to do that: join in! Learn about new cultures! There’s nothing wrong with embracing new cultures, or even learning about them! And if you get called out for doing something prejudiced, apologize, learn, and move on. It’s simple. Fearing cancel culture for making a mistake need not be a reason to remain intolerant.

Even though anti-Asian racism is now a much larger problem, we cannot ignore racism against other people of color, especially Black and Indigenous people. Although people of color committed many of the attacks against Asian people — and we ought to hold them accountable too — we also ought to not let that turn into anti-POC sentiment. That’s the point of white supremacy and the model minority myth — dividing people of color amongst each other. So what I urge is for all of us, Asians, Blacks, Latines, Native Americans, and yes, whites as well, to combat racism together. It’s not our skin color that’s the problem; it’s white supremacy. It’s racism.

And no, a dumpling is not “disgusting.” It’s food. Maybe give it a try?

Thomas Le • Apr 1, 2021 at 3:48 am

Thank you for speaking out and for sharing Ian! Very nicely crafted piece of writing!