Radnor’s Worker Shortage

November 19, 2021

At this stage in the pandemic, post-quarantine and post-vaccination, returning to normal appears like the next plausible step on the perilous staircase of the past two years. Radnor has begun full in-person schooling, restaurants and shops appear thriving with business, and sports return to the Main Line. But with all this anticipated economic rebound, there seems to be one crucial component missing: workers. The amount of individuals employed in the workforce cannot sustain the new rise in activity brought by the decrease in pandemic cases.

Examples of this phenomenon – coined as a crisis by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce – exist everywhere. Ever stop to wonder why your last class didn’t have a substitute when the teacher had to miss? Lack of substitutes. Ever had to drive yourself to a sports event because another team had a game at the same time? Lack of bus drivers.

To address this issue, Radnor is actively trying to recruit more workers. Both the district website and recently added signs outside the high school convey the message “We’re Hiring in Radnor!,” with a provided QR code to the human resources employment page. Occupational opportunities Radnor currently offers include paraprofessionals, bus drivers, and food service workers.

“We’ve been seeing a decline [in workers] but of course the pandemic has really affected that with us,” explains Todd Stitzel, Radnor’s Director of Human Resources, to the Radnorite. “It’s just a tough market out there all around. People used to go to education for some security when they needed to find jobs, and right now not everybody needs to find a job. So it’s definitely hurting us which is in turn hurting the educational process because we don’t have as many staff as we’d like to have.”

Elaborating on the student experience, Mr. Stitzel mentions how shortages affect day-to-day school life: “You notice down at the high school, there’s times where there aren’t as many subs as there used to be, which is affecting some classes… When you’ve got less substitutes and less teachers in a building, the students are going to suffer a little bit because there aren’t as many people there for students to go to talk to, there aren’t as many people to pick up the extra clubs and activities.” Radnor students may feel affected by the lack of staff at the high school, but our district does not stand alone. Mr. Stitzel reflects on county HR meetings consisting of other districts experiencing the same crisis.

Spreading far beyond the world of education, the worker shortage creeps into every aspect of American business. In particular, shops and restaurants populating the streets of Radnor suffer under reduced staff. When asked how current demand relates to the present shortage, Sean King, manager of Jules Thin Crust Pizza in Wayne, commented on the inability to anticipate the current economy. “Especially at this location, because the business has been picking up… there’s difficulties in trying to meet customer expectations, while also trying not to go over or under expenses being that you don’t know what tomorrow’s gonna bring,” explains King. “And I guess trying to find that balance is what’s been the most difficult because you spend too much money then you’re going out of business, but you don’t hire anybody, no one’s going to want to come in because the service is not going to be good.”

King points to the trend of more experienced workers seeking higher-paying employment after COVID, and how this impacts the restaurant business: “There’s not a shortage of new employees, as far as new to working. But as far as people with experienced skills, they tend to gravitate higher up the chain of employment.” What’s left for many businesses is less-skilled workers just joining the force. “[This] isn’t a bad thing, because I think that it opens up a lot of opportunities to people that are just getting into the workforce, looking to start their own experience,” King elaborates. “I think it’s just more of a matter of, for like your common job, the availability isn’t really there. But that doesn’t mean the quality isn’t there.”

King’s experiences with new employees directly relate to Radnor students in the workforce. Teenagers in Radnor have always found employment within the community, but finding a suitable job as a high school student has only become easier with the worker shortage crisis. Sabina Eraso, a Junior at Radnor who works at Italian restaurant Pietro’s, had a very easy going experience when job searching this fall. “I got my job at Pietro’s almost immediately after turning sixteen last September,” tells Sabina. “Many of my friends work there, and I would come in to see them at the restaurant. Eventually they needed workers bad enough that they asked if I wanted a job. Pretty soon after, I was trained and handling takeout orders.” Restaurants in particular have struggled with hiring staff following quarantine shutdowns, and high schoolers across Radnor have served a key part in helping these businesses.

As with most Radnor-centered trends, our troubles represent a small piece of a much larger societal puzzle. The worker shortage is not localized, but has proliferated throughout the country. As of September, five million fewer people were working compared to before the pandemic, and three million fewer people were actively searching for jobs. Many US forecasters incorrectly expected a sudden influx of workers with the end of expanded employment benefits and the reopening of schools and businesses. Now, even the Main Line struggles to garner enough workers to meet the insistence of post-pandemic expectations.

The shortage seems like a continuation of COVID in a world healing from the pandemic. Many still feel hesitant returning to high-stress work situations that put them at risk for contracting the virus, such as driving, working in a restaurant, or helping at a school. People found staying home to care for out-of-school children an easier alternative to working during the pandemic. This situation especially affected women; in a report on women’s employment last March, Mckinsey found that “[o]ne in four women are considering leaving the workforce or downshifting their careers compared to one in five men.” Even with fewer and fewer cases arising, leading to more spending and need for workers, some don’t see the need to return to their occupation just yet.

Essentially, we are living the effects of a supply and demand problem seemingly pulled directly from Chapter 3 of your Econ textbook. Radnor’s resident economist Todd Miller, who teaches all Macroeconomics classes at the high school, gave his point of view on the worker shortage: “Everything comes down to supply and demand. But I think the supply, as in the supply of workers that are willing to take jobs, is not high right now. I think the demand for certain types of jobs, like your Wawa, your restaurants, your grocery stores, they’re out there.”

The shortages in our resurrecting world don’t just apply to workers, but also material shortages on goods across the country. If finding a Halloween costume that would arrive in time proved unusually difficult this year, lack of resources can explain. A new appliance for your home may have rested on backorder for weeks, or maybe you’re curious about potential delays on Radnor’s construction progress. The answer relates directly to the lack of workers: not enough people, not enough ability to produce, manage, and transport goods across the country.

Bill Dolan, the Director of Operations for the ADA Accessibility and Wellness Infrastructure Project at RHS, gratefully remarks that the construction process has not suffered from lack of workers so far. However, Dolan recognizes the global trends in worker shortages that contribute to the possibility of difficulty in obtaining materials for the project: “As manufacturing facilities struggle to staff their operations, the production output suffers. And at the same time, the demand for materials has not dropped off. Top that off with the challenges in the global supply chain, and raw materials are just not getting to factories as quickly, so finished goods are not leaving factories fast enough to catch up on demand.”

Thankfully, the project at RHS has taken into account the implications of the worker shortage on a variety of items needed for the construction. “Information on materials shortages fluctuates,” Dolan states. “Sometimes we are told that an item is currently projected to have a very long lead time, and then we are pleasantly surprised when the item arrives earlier than projected.” For the meantime, Radnor’s contractors always order supplies well in advance, anticipating a potential delay in delivery.

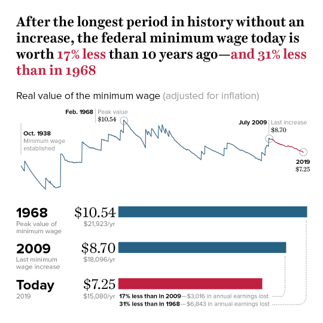

At this point, no one can deny the worker shortage, as signs of its severity flood our everyday lives through interactions with schools, businesses, and even construction processes. However, many disagree on the exact reason why this economic trend is taking place; better put, no one can decide who to blame. Some may choose to target the generous unemployment benefits provided by the government during COVID. While many lost their jobs due to pandemic closings and cutbacks, the extra support checks may have turned workers away from searching for occupations once the country started returning to normal. Others tend to blame low wages; the American minimum wage has not risen to match inflation or productivity rates. Essentially, those individuals argue that the current minimum wage, which has changed little since the 80s, cannot support the cost of living today. Following the pandemic, employees no longer express the incentive to work difficult jobs for an insufficient amount of money.

Many argue that individuals will only start flooding back to work once their savings from COVID have run dry, and others recognize the shortage as a collective strike for better working conditions. Workers have been demanding improved wages for the better part of a decade when the Fight for $15 Movement took off in 2012. The U.S. remains one of the only first-world economies with no mandated vacation days; 23% of American workers have no paid vacation and 22% have no paid holidays. And on top of all this, the pandemic revealed the intense dangers of certain essential professions, such as nursing and working in a grocery store. Many don’t see a benefit in returning to low-paying jobs only to suffer under the stress. The shortage has revealed just how desperate the worker has become to escape the pressuring demands of holding a job in America.

University of Michigan economist Betsey Stevenson told the New York Times that “it’s like the whole country is in some kind of union renegotiation.” In an interview with Bloomberg, Anthony Klotz, an associate professor of management at Texas A&M University, stated it’s possible that a “great resignation is coming.”

“I think the real cause [of the worker shortage] is people are re-evaluating,” explains Mr. Miller. “And we saw this in the Great Depression, we saw it in the Great Recession.” To solidify the idea that American workers want better for themselves and their work environments, Mr. Miller pointed out that 65% of workers are searching for new careers: “I really do believe it’s a readjustment for a lot of people.”

America has created an environment in which workers are willing to manage the risks of unemployment to avoid returning to their jobs. This unfortunate case combined with the pandemic’s stimulus checks create a messy set of pillars upon which the economy cannot stand.

We have recognized the problem, but what can America do about it? We can take advice from companies such as Uber or Wawa, which have begun offering increased pay to try and draw in more employees. Or, maybe the situation is best left alone until workers start needing the money from employment enough that they return. Mr. Miller expresses a clear viewpoint: “[Jobs] are offering more money and that still isn’t drawing people back.” To most experienced economists, getting shortages back on track involves no involvement or interference. “I just think, as anything with the economy, it takes time to work itself out,” Mr. Miller stresses. “Everything just has to readjust, and unfortunately that takes time.”

Many say that however companies, businesses, and townships decide to act, the general population may begin to acknowledge the outdated condition of America’s workforce. From a social and political standpoint, change within this sector looks to be a focal point of reform in the remaining aftermath of COVID. Raising wages might not hold the answer, but increasing vaccination rates, continuing with booster shots, and accommodating more to the social and emotional needs of employees represent a few ways in which workplaces may strive to create safer and more encouraging environments for potential workers.

As for Radnor specifically, what can businesses and the school district do to survive this shortage? Mr. Stitzel explains some of the township’s strategies for encouraging more substitute teachers to join Radnor’s workforce: “We’re trying to do everything we can, we’ve raised rates for substitute teachers to try to get more in the building. We’ve done what we call Building-Base subs, we’ve opened up positions [where] a substitute can report to the same building every day for the entire year to give them some continuity.” In the past, substitute teachers awaited early morning phone calls, around 5:30 or 6:00 AM, for job assignments. After the pandemic, this system no longer stands; current substitutes now select positions online. Stitzel also highlights the district’s use of vendors to find substitute teachers and the state’s Guest Teacher Program, in which individuals with a bachelor’s degree train to receive substitute certification.

When asked if these policies show progress in garnering more workers, Mr. Stitzel came to a similar conclusion as Mr. Miller. “I think they’ve worked where they are, but I think we’re so far depleted,” replied Stitzel. “It’s gonna take some time in order for more people to get into education, to ultimately get more certified people.”