Understanding Abortion Laws Around the World

May 27, 2022

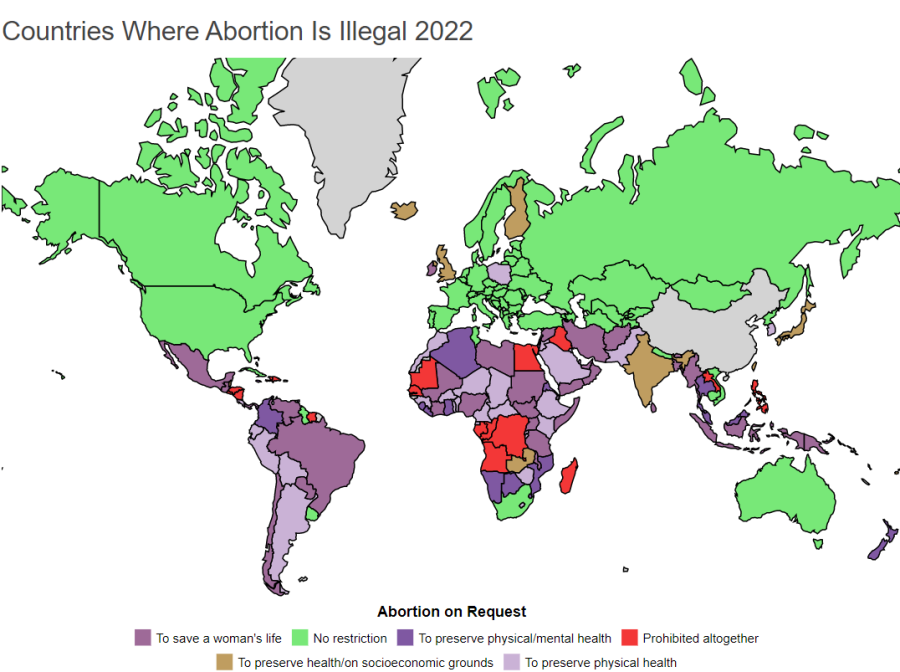

Around the world, national governments write laws that can either regulate and restrict the lives of their citizens or give them complete bodily autonomy. Amidst mask mandates, and possible vaccine requirements, the question of “my body, who’s choice?” has sparked heated conversations. Before the pandemic, the controversial topic of abortion lay at the heart of discussions surrounding medical freedom. Interestingly, the cultural values of countries around the globe play a large role in this ever-evolving abortion debate. And with the upcoming reversal of Roe V. Wade in the United States, a 1970 court case that legalized abortion for U.S. citizens under the constitutional right to privacy, global citizens are more eager than ever to discuss abortion laws and their impacts on society.

The decision of how to treat abortion in a country is a unique case for policy writers, because cultural and religious values can affect how a population understands abortion. Should it be illegal in all cases? Only when the pregnant person’s life or health is endangered? Or always legal? Often, local communities pre-write the laws that make up a nation as unspoken moral obligations, existing separately from courthouses and government buildings.

Madame Daryoush, for instance, a multinational woman born in Iran who teaches French at Radnor High School, feels that people’s views about abortion are “different depending on how… [they are] raised, [their] morality, religious [views], spirituality” and their responsibilities growing up. Governments decide the rules, but communities and cultures foster them through generations of deeply-rooted values. Iran’s abortion laws both state that abortion is illegal unless the mother’s life or health is threatened by their child and prevent the availability of abortion pills on the Iranian market, yet Madame Daryoush remembers that her values were influenced and “challenged not … [by] the government but the society itself.” She lived in Iran until she was 12, where she was first exposed to the cultural values of her nation, then moved to Belgium and later the U.S. She recounts her life in Iran as a little girl raised by a progressive, well-educated family who strived to let her develop values independent of her government until she was exposed to the values of different countries at an older age.

In other countries, as pressure on nations to release restrictions surrounding abortion laws increase, abortion bans have grown progressively more liberal. In Pennsylvania, abortions are legal before 24 weeks of pregnancy; meanwhile, many national governments have released restrictions on abortion if the life or health of the pregnant person is endangered.

However, restrictions on the rights of minors to complete abortions are less clear-cut. Pregnant teenagers under the age of 18 in Pennsylvania, for instance, must obtain permission from at least one parent to undergo abortion, but they can also receive private permission to have an abortion from a court judge without the parents’ knowledge, a process called a judicial bypass. During the hearing, a judge must determine whether the teenager in question has been educated by a medical provider of their options and the procedure’s risks, and whether they are mature enough to make an independent decision; the judge cannot refuse to grant permission if both these conditions are met. If the judge does not confirm their decision within 3 business days of the hearing, the minor has the right to appeal to a faster, higher-court hearing in hopes of receiving permission sooner. For pregnant minors in Pennsylvania, a judicial bypass can be a convenient way to legally and safely abort without worrying about their parents’ opinion, especially considering that only 5 court cases in the last 26 years in Pennsylvania out of thousands of others have denied the minor the right to an abortion; if denied, a lawyer can appeal to a Superior Court and obtain an updated decision within 5 business days. Excluding a denial, judicial bypassess can be successful without a lawyer, and 36 states within the United States allow minors the right to the process.

Although many minors will no longer be able to take advantage of this process if Roe V. Wade is reversed, residents of Radnor may not have to worry about their abortion options being restricted by any national decisions after the Radnor Township Board of Commissioners voted 4 to 2 to enact a preemptive abortion access ordinance on May 23rd. The majority vote decided to remove the ability of Radnor police forces to arrest or otherwise detain persons “accused of facilitating[,] providing, or receiving abortion services,” according to the ordinance. The board’s president and vice president, Moira Mulroney and Jack Larkin, respectively, agreed that early action was necessary to ensure that the right to abortion would be protected by the township’s council no matter if or when Roe V. Wade is reversed. Moira stressed the importance of a rapid local response to the nation-wide reversal before it became “too late” and the case was settled, and Larkin emphasized the role of the Radnor council in preventing national and state governments from “enforcing what is plainly a violation of a constitutional right to privacy.” Radnor police have not yet signed on to the plan, but the ordinance, which will be finalized on June 13th, still promises to protect the right to abortion at a local level through the board decision alone.

In other places, restrictions have tightened, and abortion laws worlwide remain varied. Out of the 56 countries that have significantly changed their abortion laws in the past 27 years, 3 have increased abortion-related restrictions. In Nicaragua and El Salvador, abortion is prohibited in all cases; in Myanmar, Somalia, and Brazil, abortion is only legal if the life of the pregnant person is in danger. Poland allows abortions if the health of the pregnant person is threatened or in cases of rape or incest; meanwhile, only 13 countries with a population above 4 million people allow on-request abortion acess for all possible cases.

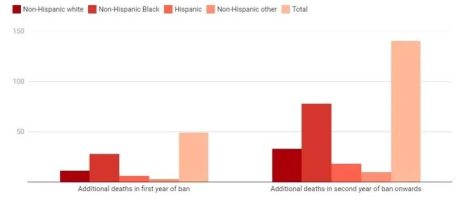

Countries that enforce stricter abortion bans have also exhibited increased maternal mortality rates. Pregnancy-related deaths will increase by an estimated 21% in the United States after the second year following any abortion ban that limits the legality of abortion to special cases only, such as when the pregnant person’s life is endangered. Often, the conditions underlying these deaths, such as cardiovascular disease and infections, could have been avoided with a safe abortion. Instead, when abortion bans take effect, leading pregnant people to either carry their baby to term despite the risks or resort to less-than-safe abortion options, they suffer more, and their underlying illnesses worsen— meaning higher mortality rates for pregnant women.

The safety of the mother has proven a top concern even among members of societies who believe abortion should be banned in all other cases. After all, if a pregnant person cannot safely carry their baby to term, an important question arises, and one that Madame Daryoush asked as well: “Who are we going to keep? The mother, or the child?”

Alternatively, if the life or health of the pregnant mother is not endangered by their child, the laws surrounding abortion become more morally gray. In these cases, some national governments hold that abortion is always illegal after a certain amount of time following conception. In Texas, for instance, abortion is only legal during the first 6 weeks of pregnancy, when a fetal heartbeat cannot yet be detected. This law poses a problem for pregnant people who do not get the chance to decide whether they want to have an abortion because they have not realized they are pregnant within the 6-week window. More restrictive abortion laws prevent pregnant people’s access to safe abortion methods because governments imposing such laws block their accessibility. Instead of swallowing an abortion pill, future parents in these countries must resort to unsafe abortions, increasing maternal mortality rates by risking their own lives with illegal and harmful pregnancy terminations.

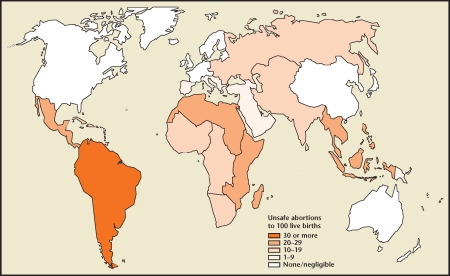

Turning to illegal, riskier abortion methods, sometimes leads to the death of the pregnant person. The U.S. National Library of Medicine reports that out of the 42 million women worldwide who unintentionally become pregnant and choose to abort their child every year, 20 million do so illegally, often using unsafe abortion methods. These include ingesting harmful fluids such as bleach, inserting a foreign object into the uterus, and intentionally causing trauma to the abdomen or uterus through cutting, stabbing, and eventual infection due to an unhygienic environment—all to kill the fetus. About 68,000 women die annually from such abortions, which contribute to 13% of maternal mortality rates.

Madame Daryoush recalls that many of the abortions completed in Iran, for instance, were done “especially [by] young girls working under the pressure of their boss in the workplace; they ha[d] … [a] relationship and then they [were] … pregnant. These [were] … the young women who [got] … abortion[s] illegally.” Although these same young people living in countries with more restrictive abortion laws often turn to these illegal and unsafe methods, governments such as Iran’s and Brazil’s still try to limit abortions altogether. In fact, Iran’s laws threaten 10 years of imprisonment for a pregnant person found to have carried out an illegal abortion and the death penalty if such abortions are completed on a large scale. However, these laws have not prevented the estimated 300,000 to 600,000 illegal abortions completed in Iran per year.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2709326/

Many others maintain that a fetus has a soul that cannot be ethically destroyed through abortion, and that governments that choose to allow abortion produce members of society that grow “overzealous in reaction to excessive liberation,” according to Madame Daryoush. Those who share this idea argue that when governments legalize abortions, they open the way for people to act more sexually carelessly, leading to more unintentional pregnancies and more abortions.

In contrast, data indicates that less restrictive abortion laws correlate to less cases of unsafe abortions, and therefore less overall harm done to the pregnant person. The 82 countries with the most restrictive abortion laws in the world exhibit a maximum median rate of 23 unsafe abortions carried out for every 1000 total abortions, while countries with more lenient laws report only 2 unsafe abortions for every 1000. Abortion-related maternal deaths are also more frequent in the former countries—34 deaths per 100,000 births—compared to the latter countries—at most 1 death in 100,000 births.

This trend can be examined in the abortion-related maternal mortality rates of countries that significantly changed their abortion laws. When new abortion restrictions were written into law in Romania in 1966, abortion-related maternal deaths increased from 20 deaths per 100,000 childbirths in 1960 to 148. After the Romanian government reversed the law in 1989, the ratio dropped to 9 deaths in 100,000 births by 2002. And when the South African government legalized abortion for all cases and increased its availability to on-request abortions in 1997, the 1991-2001 Confidential Enquiry Into Maternal Death reported a 91% decrease in abortion mortality since 1994. Abortion-related deaths especially decreased for young women, previously the top group for abortion mortality in 1994.

The abortion rate in the most restrictive countries, including those in Africa and Latin America, is 29 more than that of the least restrictive countries, typically European nations such as Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands. Although correlation, no matter how strong, does not prove causation, these data suggest that governments can better control their maternal mortality rates, especially those caused by unsafe abortion methods, by regulating abortion in their country more flexibly.

The selection of laws a nation should implement to reduce their maternal deaths show how national legislation can universally determine the amount of abortions, legal and illegal, carried out in the country. Firstly, a common trend in nations with more restrictive abortion laws shows that they share not only common legal restrictions but also similar contraceptive availability and use rates. As exhibited by the Russian Federation, abortion rates dropped when contraceptives become more accessible because they prevent unintentional pregnancies. Of course, advanced contraceptives can only bar pregnancy if the country that distributes them can afford to do so. Because many of the countries maintaining the world’s most restrictive abortions laws are developing nations, their governments may not be able to fund effective contraceptive distribution, leading to more unwanted pregnancies and more abortions. Therefore, developing countries contribute to 25% to 50% of global maternal mortality rates.

Still, despite the higher rates of abortion-related deaths in countries with stricter abortional alws, national governments remain reluctant to relax abortion restrictions, often because religious and cultural values complicate the ability of policy writers to introduce new flexibility into abortion laws. This holds true for many Iranians, whose government, Madame Daryoush explains, legalized abortion in 1977 only if the life of the pregnant person was endangered by their child. If the pregnant person’s life is safe, however, “there’s no need for abortions, illegal or abnormal. In Islam, after [the] revolution, [the] Islamic rulers, they came up with this idea… a child after 4 months of conception has a soul. Once a child has a soul, [people] definitely cannot do it [abortion] unless it puts the mother in danger.” Leaders are resistant to permitting abortion when the cultural values of their country dictate otherwise.

Regardless of religious and cultural considerations, the question of whether to abort a baby is not an easy one to answer. Birthing, raising, and providing for a child is no small feat, a fact that many RHS students came to understand during their two weeks caring for “egg babies” for their AP Psychology class. Although carrying an egg in a basket and taking pictures of it in no way bears the same responsibility as caring for a living child, the project demonstrated the amount of attention and carefulness that must be exercised to watch even a small object, let alone a breathing baby. When countries restrict abortion, pregnant people that are not ready for parenthood are left with children that they may not have the resources to properly provide for. No easy answer exists for how any given country should govern its citizens in relation to abortion, because no single group of people hold the exact same beliefs about pregnancy, body rights, or the value of a life.

All over the world, the abortion laws regulating a nation can determine the future of millions of people. As many restrictive countries begin to relax their grip on their citizens’ lives in response to calls for easier accessibility to abortion, a select few regions have tightened their laws, including Texas and Poland; depending on the perspective, such changes can be seen as either harmful regressions or progressions necessary for maintaining important cultural values.

Questioning whether a pregnant person has a right to choose their own life over their child’s is crucial for continuing discussions among the international community and promoting the writing of new legislatures. No matter their historical or religious background, every protestor, politician, activist, and global citizen can benefit from understanding the extent to which abortion—illegal, legal, safe, or risky—impacts generations of families and sets the parameters for hundreds of nations’ views about life around the world.