The business of saving local news

October 14, 2022

Waiting in the Radnor Memorial Library, early for a meeting, I noticed my position right next to the wall of various laminated newspapers and magazines. Looking up at the display, with only two local papers reporting on townships all across Southeastern Pennsylvania, my hopes of learning something new about Radnor fell away. How are we supposed to know what’s going on in our community?

The answer is we don’t, and that’s also where the problem lies. A couple decades ago, local newspapers were the cornerstones of any community, connecting people through stories, events, even wedding announcements and obituaries. Local news covered the details, the specifics, the inner workings of our towns and counties. It framed our lives.

Now, local journalism has all but disappeared. About 1 in 5 newspapers has closed over the past decade and a half, and 65 million Americans live in counties with only one local newspaper, or none at all. This creates what’s called a “news desert,” or a community that is lacking a resource for local information. But why do you need to read a newspaper when you can access anything you want with the click of a button? In the 21st century, it might seem like the whole world is available at your fingertips, but the whole world tends to obscure the importance of your doorstep.

Almost everyone over 18 in America can vote for the President, and people in Pennsylvania can vote for our Governor and Senators and etc. etc. But there’s usually more than one name on the ballot, and your local elected politicians can decide a lot about what happens in your community, even for broader issues such as COVID regulations and abortion laws.

However, national news sites aren’t likely to cover your school board election anytime soon, and communities lacking strong local journalism have no easy way of learning information about candidates and important issues. They might turn to Facebook or blog posts to fill this void, but these sources lack the key component of any credible news outlet: integrity. Journalism is centered on clear, unbiased, and factual reporting. Journalists focus on transparency and the truth, without their own viewpoints interfering (except for in editorials and op-eds, of course).

When asked what value she felt local news had on a community, former journalist for The Philadelphia Inquirer, Mari Schaefer, spoke on the principle of integrity. “[Journalism] brings honesty and truth to the process. It also provides information… there is that sense of impartiality, of trying to be fair and honest.”

Before heading to vote in a local election, nearby news outlets can ensure with this integrity that you understand each candidate, their past political experience, and the issues they will choose to prioritize. Avery Rome, former journalist and editor for The Philadelphia Inquirer, spoke to me about the importance of local news in the voting procedure: “The real fear of people losing newspapers now is because that’ll kill democracy. How will you know what the issues are? How will you know how the government’s spending your money?”

While speaking with Avery, she mentioned stormwater issues in Pennsylvania that have led to rising water levels. Many construction projects currently underway, including that on South Wayne Avenue right across from Radnor Memorial Library where we spoke, are centered around this problem. Without local news, many people have no idea why their commute to work has suddenly been interrupted by a closed road or dug-up parking lot. Without local news, information doesn’t reach the community.

“A popular government, without popular information,” said James Madison, “or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a tragedy; or, perhaps, both.” Historically speaking, our government relies on the press to provide communities with the materials to stay informed. If citizens do not have local news to educate them of their voting options, maintain transparency in the government, and provide them with unbiased information, they will not have the necessary faculties to participate in democratic procedure. Hence, the structure of our government crumbles into disarray; how can our democracy remain stable if those voting to decide its leaders are uninformed? Journalism has been coined the fourth pillar of our government, helping to support it alongside our legislative, judicial, and executive branches. Local news contributes to a sense of community and civic engagement.

“They don’t know what’s going on,” replied Mari when asked how a lack of local journalism impacts a community. “And I think it creates a vacuum of information.” Mari mentioned the issue of food insecurity, and how individuals suffering don’t have the available materials to help them. “There are all these stories that just aren’t happening anymore, so people don’t know where to go for resources. There’s that lack of knowledge.”

But what has facilitated this decline in local news? A Knight-Gallup study published in 2019 found that Americans trust local news more than national, and the decline of local newspapers has a direct correlation to political polarization and partisan voting. A Bloomberg study in California showed that shrinking local newsrooms leads to fewer candidates running for mayor. As summed up by a Brookings report detailing the local journalism crisis, “the need for local journalism has not changed overtime, but the economic dynamics capable of sustaining a profitable model for local journalism have.”

The past “economic dynamics” that upheld local journalism found their roots in advertising, a system in rapid decline. There has been a 68% drop in newspaper advertising revenue from 2008 to 2018, and the growth of digital advertising has facilitated this decrease. Moreover, Facebook and Google, which account for 58% of digital advertising revenue nationally, account for 77% in local markets, serving as local news’ greatest competitors.

The quality of reporting depends on the resources available to fund newspapers, and advertisement earnings cannot withstand this expense anymore. “The reason [local news] is falling apart is because of the internet and the business model,” comments Avery on the impact declining revenue has had on news content. “Without the car ads, without all of that advertising support, it’s hard to make it work and you need to spend money. Because really difficult stories take time.”

Apart from advertising, the old print subscriber model also cannot function as a sustainable source of revenue for news outlets. Fewer and fewer individuals become motivated to spend dollars on subscriptions when we live in a world of search engines. Newspapers, when first transitioning online, foresaw this trend and gave their stories to the public for free, yet soon learned they could not profit from this model. After changing back to subscriptions, they found that consumers simply were no longer interested in paying for information.

As for the economic impacts of the COVID-19 virus on local news outlets, it’s the same story most other businesses in America faced throughout the pandemic: loss. During the height of quarantine, local newspapers were losing 30-60% of their advertising. As of 2020, more than 1,800 local newspapers closed in the past 15 years.

In addition to advertising, print subscriptions, and COVID losses, local newspapers have struggled under ownership changes. The owner determines the publication’s content, focus, and its business models. According to the University of North Carolina’s site devoted to the research of news deserts, more than half of all newspapers have changed ownership in the past decade, some multiple times, and the largest 25 newspaper chains own a third of all newspapers, including two-thirds of the country’s 1,200 dailies. More and more frequently, independent and family ownership of local publications has declined, leading to the purchase of papers by larger corporations. This concept of “big guy” ownership translates into newspapers being controlled by money-making enterprises with no individuality or community connection.

The phenomenon of ownership consolidation has contributed to the rise of what UNC’s research coined “the ghost newspaper.” Many surviving local newspapers purchased by large companies have been gradually weakened to a point of ineffectiveness. A third of the 1,800 papers that were lost in the past 10 years slowly faded away, their operations disintegrating until the previous quality could no longer be maintained. This process often includes consolidating with larger papers, selling the newsroom building, letting go of staff, reducing output and quality of content, and eventually disappearing as a publication entirely.

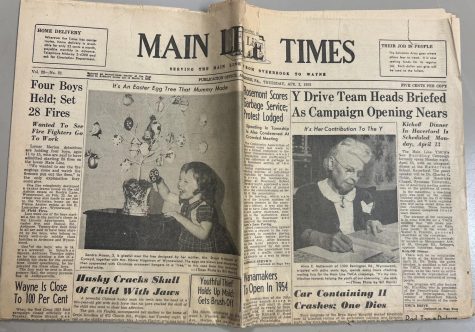

I didn’t know until speaking with local journalists that the disappearance of The Suburban & Wayne Times, Radnor’s past publication which used to operate in the space where the Sugaree now sits on North Wayne Avenue, is a textbook example of the ghost newspaper. The Suburban gradually merged with other nearby publications to form The Mainline Times & Suburban, which currently covers a wide array of townships and communities across the area. When I scanned the paper at the library, I noticed how the edition spanned from Norristown to Lower Merion to Pottstown; rather occasionally, one can find stories reporting on Radnor.

Void, quiet, and desolate are words used to describe abandoned houses, not newsrooms in their prime. Yet Sam Strike, a former journalist for The Suburban who experienced the merger, told me how she was the last reporter working in the old North Wayne building before the space was sold as a part of the consolidation process. Sam expressed a loss of community when the paper moved locations: “I think that you just lost more of that local connection, because it’s like, is a person from Wayne really going to drive all the way down to Ardmore to do something with the newspaper? Not likely.”

Sam also related her experience covering commissioner meetings, school board meetings, and candidate interviews in order to inform citizens about their government, but the same coverage is no longer possible due to the consolidation and disappearance of The Suburban.

“A hedge fund at some point bought it,” related Sam on the future of The Mainline Times & Suburban after she left. “They don’t really care about the community. They just want to make money.” Sam explained how The Suburban used to be owned by a local family, but most community newspaper owners lost the ability to profit from journalism and had to sell to larger companies with no interest in maintaining steady reporting.

To understand more about how our local newspapers have transformed over time, I talked with Jodine Mayberry, former columnist for The Delaware County Daily Times. Jodine’s husband was a previous editor of the publication, and her son continues to work on the paper. Through her personal connection to The Daily Times, Jodine related the story of its most recent years under a hedge fund ownership.

“The local news has been dying for many years,” explained Jodine, “but Alden Global Capital is the prime mover to destroy what’s left of it… They swoop in, buy up chains of newspapers… They suck the life out of every dime.”

Alden Global Capital, as of May 2021, has become the second-largest newspaper publisher in the United States as the majority shareholder in MediaNews Group (MNG). In addition to a wide collection of small, local papers, MNG owns The Denver Post, the Boston Herald, and most notably the Chicago Tribune, which has suffered horrible losses and cutbacks as a result of the company’s ownership. Alden’s reputation is of a cut-throat, money-making operation; The Washington Post has called them “one of the most ruthless of the corporate strip-miners seemingly intent on destroying local journalism,” and Vanity Fair prefers to classify Alden as “the grim reaper of American newspapers.”

MNG, or more specifically Alden itself, now owns The Daily Times, making money on their legal advertisements and costly obituaries. The hedge fund shows no interest in the journalistic spirit or community of the paper, instead sparing no one in an effort to make as much profit as possible.

“Alden has been unbelievable,” explained Jodine. “They made all the newspapers sell their buildings. Then they would go on to find a drugstore or something and they would renovate it and they would put the newspaper in there. When the lease was up after the first year, and this happened to The Daily Times, [the reporters] were sent home and they were told they would have another office in a couple months.” Years later, the newspaper continues to operate entirely through email, a system which destroys the collaborative spirit of the journalistic profession.

According to Jodine, Alden has steadily been buying out reporters, and The Daily Times now employs only three journalists trying to cover all of Delaware County. Similar to Sam Strike, Jodine mentioned how local news previously covered government meetings for all townships, but now there’s not enough people and resources present to maintain the publication as it used to function.

“Gradually, little by little,” said Jodine, “the paper lost all of these things that help create community, because they didn’t have the people to do them… People buying the paper didn’t realize what they were losing.” Jodine best described this long process at The Daily Times using lyrics from the Joni Mitchell song “Big Yellow Taxi:” They paved paradise, put up a parking lot.

“You don’t know what you’re missing until it’s gone,” commented Jodine about the song, but in the case of the fall in local news, “They don’t even know what they’re missing when it’s gone. They have just gradually gotten used to this over the years.”

Not much has been done to save our local papers despite the degree of Alden’s operations and attention in the media. Evan Brandt, the last remaining reporter for the Pottstown Mercury, which was acquired by Alden in 2011, even appeared on “60 minutes” for his efforts to speak to Alden’s president. Although the hedge fund’s unresponsiveness revealed just how little they care for the future of local journalism, the plight of small publications remains unaddressed. “When you hear people talking about saving the local press,” commented Jodine, “you hear about the big papers, like The Inquirer. But they don’t talk about the little papers who serve the counties outside.”

Throughout the entire decline of the local news and the growing ineffectiveness of its business model, one thing has not changed: the need for information. When local publications can no longer provide a sense of community through fair and professional reporting, many turn to social media for their updates. Tailored to provide users with information that only appeals to them personally and politically, social media sites hardly help a person learn more about others and keep an open mind. Misinformation, preaching false and sometimes dangerous knowledge, can easily run rampant online. Yet social media is another gateway to information that takes on a national audience, and many looking for news about their own community have had to look elsewhere.

Many of the journalists I spoke with mentioned that they receive their news from local sources such as The League of Women Voters, their commissioners’ emails, and the township website. They also mentioned operations such as Patch and NextDoor, which are larger companies working to create “hyperlocal” coverage of small communities. Sam Strike, who worked as a journalist for Radnor Patch after The Suburban, told me of her experience with the site: “I thought Patch was a cool concept, I thought it was really awesome. You could send out these alerts, it was very interactive, people were on Facebook talking about issues. It was really cool.”

However, Patch suffered under the same financial pressures that haunt local newspapers. “You can’t make money at the end of the day,” said Sam, “or the money that you needed to.” According to Sam, most Patch reporters were laid off back in 2014 over a phone call, and now sites are typically covered by only one writer also working on multiple other communities. Moreover, anyone, regardless of journalism qualifications, can publish information on Patch without proper fact-checking.

Sam explains how Patch, despite good intentions, is now “a shell of its former self” rather than the local news reviver it hoped to be. Patch can provide almost instant updates on what’s happening in your neighborhood, but it doesn’t meet the qualifications for true local journalism, rather contributing further to the proliferation of the rumor mill.

If speaking with local reporters told me anything, it’s that true journalism is defined by storytelling, learning, and history. Newsrooms are places filled with excitement and energy. Journalists are characterized by their passion for truth, honesty, and the first amendment. Newspapers tell the stories of your community and help build connections. Without local journalism, we suffer.

So how do we move forward? Some speak of government intervention through public funding and tax breaks, but ensuring this money doesn’t end up in the pockets of Alden’s senior managers might prove difficult. Moreover, letting the government interfere could politicize and polarize local news. The Local Journalism Initiative, proposed by the Columbia Journalism Review, stresses the importance of nonprofits, rather than hedge funds or politicians, in saving local news.

One example of this in action is with The Philadelphia Inquirer, now owned by the Lenfest Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to investing in new avenues of sustainable journalism. The Inquirer is currently the largest newspaper in America acting as a public-benefit corporation. Operating within the tenets of “Journalism, Innovation, and Democracy,” Lenfest plays an active role in ensuring The Inquirer is able to serve the people of Philadelphia without greed or a lack of connection to the paper. Lenfest’s ownership leads by example as an ethical future for journalism, despite its fragility; unfortunately, the nonprofit continues to rely heavily on donations and grants. The Inquirer, although better off with Lenfest’s morals, still struggles under the same pressures haunting all news outlets.

As I researched and discussed the future of local journalism, most everyone seems to agree that the structure of the newspaper has to adapt to a changing world if it wants to survive. For example, many publications now have an online forum in addition to or instead of a print one. Despite the tradition involved with a physical newspaper, ink and paper are costly and wasteful resources that websites can easily replace. Journalism, in order to appeal to consumers, has to embrace the online world. Another example of this process includes digital sensibility and awareness of readers, like how The New York Times has a very popular Instagram account that they use to communicate headlines and breaking news. Although national outlets have more resources, local news must embrace the short-attention spans and endless noise of the internet in order to reach audiences.

Simply put, journalism moving forward must hold onto its traditional values of supporting our government and its citizens, but it must also let go of old habits that won’t stay afloat in a new world. Judging by the current diminishing state of local news, working toward this envisioned future is going to require a lot of work, possibly even government intervention. But as Mari Schaefer said during our interview, “Change is hard, but there’s something super exciting about it. It’s freeing.”

I also asked Mari if she believed there was a cliche “light at the end of the tunnel” for journalism. Her answer: “You know, I think there always will be. I like to think that in spite of all the troubles and ups and downs in the last quarter century, we’re still here.”

Journalism exists because of individuals who believe in its power to shape a community. Journalism will always live as long as these individuals remain faithful in the importance of truth and integrity. All of us can make a difference by not only staying informed on future initiatives and supporting newspapers, but by always believing in the value of a good story.