Blood Money: Living With Type 1 Diabetes in America

The insulin affordability crisis is killing Type 1 diabetics in America, while taxpayers line the pockets of Big Pharma shareholders.

November 24, 2020

At ten years old I was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes (T1D), a chronic, incurable illness. Coming to terms with my T1D has been the biggest challenge of my life. I was pessimistic, frustrated, and angry. Living with T1D isn’t easy — people with the condition must be constantly aware of their blood sugar, managing their glucose levels through insulin injections. Now, more than five years later, I would be lying if I said I have overcome all my feelings of resentment towards T1D, but I have learned how to manage it with a more accepting perspective.

Meeting other diabetics my age and bonding over our common struggles allowed me to slowly accept the disease I will most likely be living with for the rest of my life. Primarily through attending summer camps for diabetics, where everyone runs around with glucose monitors and insulin pump wires, I interacted with people, young and old, thriving with diabetes, all of whom I greatly admire. Though camp allowed me to find a place of acceptance, I also learned I have yet to face what is arguably the greatest struggle for Type 1 diabetics in America: the monetary cost of the disease.

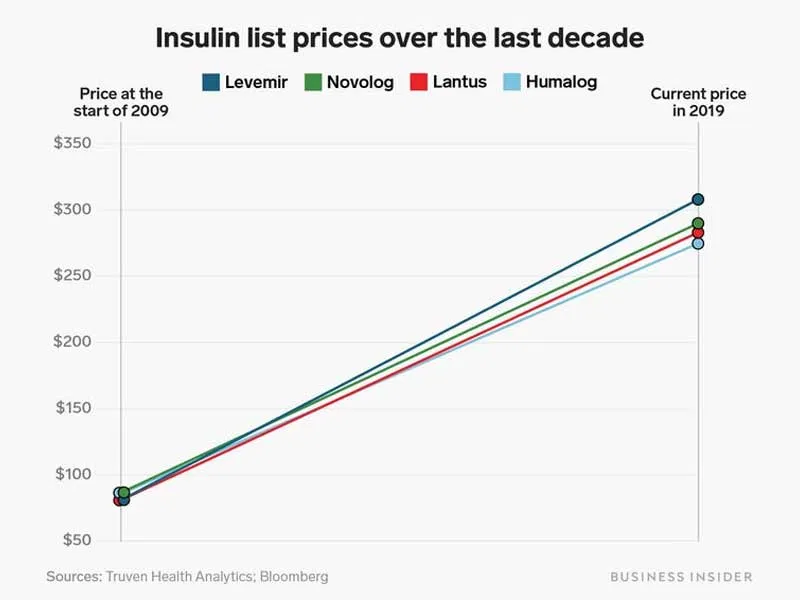

Since 2017, more than a dozen diabetics in the U.S. — with and without health insurance — have died because they couldn’t afford to pay for their insulin, while countless others have faced serious complications. Unfortunately for the nearly eight million diabetics in America who rely on insulin, between 2002 and 2013, prices tripled. Today, one 10 mL vial of insulin, about a ten-day supply, sells for $300. Among some of the campers and the younger staff, the fear of turning twenty-six and being removed from our parents’ insurance plans looms like a dark cloud over our heads.

Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, and Sanofi, the top three insulin-producing companies, are the main donors to diabetic camps across the country. Four years ago, on my last day of camp, there was a carnival and the field was filled with games, facepaint, and various inflatable attractions. My fellow campers and I were instructed to carry our bags reading “living well with diabetes,” with the Novo Nordisk logo on the top left corner, which we had decorated earlier in the week. I chose to take a different direction with my bag and replaced the “w” with an “h.” The camp director did not appreciate the humor.

That same day, the camp directors invited representatives from the donor companies, Novo Nordisk included, to see for themselves the happiness their donations had brought to diabetic children. At lunch, out on the field, one of the Novo Nordisk representatives approached my friends and me and asked us if we had fun at camp. I noted the Novo Nordisk logo on his shirt, but didn’t think anything of it, and then told him how much I had enjoyed the past week. Little did I know at the time, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, and Sanofi are at the center of one of America’s greatest public health crises. As the insulin-affordability crisis heightens, at least these companies can say that they allowed Type 1 diabetics to experience the joy of camp together, before becoming adults and, in some cases, dying because they cannot afford to buy insulin.

On Monday, May 18th, 2015, I visited my doctor’s office for what I thought would be a routine check-up. For the past month, I had been drinking gallons of water, urinating every 30 minutes, and feeling exceptionally tired. I was 10 years old and I had lost 10 pounds. After they checked my blood sugar, and my mother and I rushed to the emergency room, the doctors explained Type 1 diabetes, easing my 10-year-old self into the reality that these needle pricks and injections were a forever thing.

In the words of my new pediatric doctors, insulin is the key that allows glucose from the bloodstream to enter the body’s cells, which lowers one’s blood sugar. Unfortunately for me, my immune system had decided to attack and kill my pancreatic cells that make insulin. With no insulin to let glucose leave my bloodstream, my blood sugar concentration had become dangerously high.

Thankfully, I got to the doctor before I faced any serious complications, and I have since been able to avoid chronically high blood sugar levels by injecting insulin. Otherwise, I would be setting myself up for serious complications later in life: blindness, foot amputation, and kidney failure, to name a few.

…

To clarify, unlike T1D, Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) is not an autoimmune disease. With T1D the body cannot produce insulin, but with T2D the body becomes resistant to insulin and needs to produce more to keep blood sugar levels in a healthy range. When someone makes an “all this sugar will give you diabetes” joke, they are referring to T2D, because a person’s lifestyle plays a role in the development of T2D, in combination with genetic factors. Because Type 1 diabetics account for only 5.6% of all American diabetics, it’s easy to include us in the blanket term “diabetes.” Type 1 and 2 diabetes share a name because both conditions result in elevated blood sugar levels — between 30% and 40% of Type 2 diabetics also take insulin — but their causes are completely different.

For the sake of Type 1 diabetics everywhere, I feel obligated to include this sidebar. When I interviewed some of my friends from camp, each of them cited uninformed conflation of Type 1 and 2 diabetes as their single biggest frustration with the disease. Allie Deeble, a Pennsylvania high school junior and Type 1 diabetic, shared how “When I tell someone I have diabetes, people assume I’m Type 2. They look me up and down and they make a remark like ‘you don’t look overweight.’ Or they say ‘oh you can’t eat this.’ A lot of times people say the most hurtful things without knowing it.” I guarantee that every Type 1 diabetic has 15 stories to match.

…

Researchers are far from certain, but they suspect a combination of viral infections and genetics, can lead to T1D, but certainly not any behavior or lifestyle circumstances. So, no. No Type 1 diabetic got the condition because they ate a few too many pieces of candy.

If a diabetic’s blood sugar is high enough, they will enter ketoacidosis and, soon after, die. For an undiagnosed diabetic beginning to see the symptoms of high blood sugar, like I was five years ago, this process takes months. Like all Type 1 diabetics, I now depend on insulin to survive. If I or any other already-diagnosed diabetic accustomed to taking insulin abruptly loses access to insulin, we will die in a matter of days.

Historically, T1D was a death sentence. Doctors recognized the disease, but couldn’t do much for patients (their best treatment was prescribing a starvation diet) until 1921, when Frederick Banting, James Collip, and Charles Best discovered that they could extract the life-saving drug from the pancreases of dogs, and later cattle. They promptly sold the drug’s patent to the University of Toronto for merely $1, believing that insulin should be freely available to everyone, and won the Nobel Prize for their discovery.

The news spread like wildfire, and Eli Lilly, an already established pharmaceutical company, sent George Clowes to Toronto to see if the discovery was legitimate. After attending a lecture, Clowes sent a telegram to his boss, J.K. Lilly, saying “This is it.”

According to the book Breakthrough: Elizabeth Hughes, the Discovery of Insulin, and the Making of a Medical Miracle, Clowes received orders from Lilly to “do whatever he had to do to secure a role for the company in the development of insulin.”

Clowes lobbied the Insulin Committee at the University of Toronto, which controlled the rights to the drug, to begin production of the insulin. He insisted that they needed to act as quickly as possible to save lives and that Lilly needed a patent for exclusive rights to produce insulin, or else diabetics could be exposed to dangerous, improperly manufactured insulin off the street.

The Insulin Committee agreed and offered Lilly a one-year “experimental period” to develop and perfect insulin production. According to Lilly and Clowes’ private correspondence, this “experimental period” served the dual purpose of gaining complete control of the market by creating “[insulin] centers in every possible place, thus securing priority and cementing the doctors to us.”

For most of that year, Eli Lilly had finished developing its production procedures, and it began circulating free samples of insulin to doctors, according to historian John Patrick Swann. While the company was selling doctors on the drug, diabetics without insulin kept dying.

Towards the end of the experimental period, in early 1923, with instruction from Lilly, Clowes asked the Insulin Committee for a patent on the drug license to manufacture insulin, claiming that with a monopoly the company could “produce at the lowest cost, test at the lowest cost, sell at the lowest price, and be able to give, without charge, much larger quantities for indigent cases.”

When the folks in Toronto didn’t agree, Lilly went behind their backs and applied for a patent in the United States. The Canadians protested, but Lilly refused to change the terms of its patent application.

After Lilly’s year of exclusively developing the drug, the Insulin Committee also granted other companies the rights to produce insulin. With a year-long head start, however, Lilly remained the dominant insulin producer for another year. In 1923, insulin was its star product, generating half the company’s revenue.

Over time, other companies with licenses from the Insulin Committee began to compete with Lilly. The insulin-producing companies, now more plentiful but still few, raised their prices together. In 1941, for the first time, insulin companies were accused of violating antitrust laws. Eli Lilly, Sharpes and Dhome, and E. R. Squibb and Sons (which evolved to become Novo Nordisk), were indicted and fined by a federal jury, starting a long tradition of insulin companies facing accusations of anti-competitive practices.

This early 20th-century insulin, sourced from cattle, while life-saving, wasn’t perfect. The medication took hours for the body to process, and many diabetics were allergic to it. In 1978, the first biosynthetic human insulin was produced in a lab using E. coli bacteria and hit the market in 1982. These insulins were good, but still lacking, as they all stayed in the body’s system for 24 to 36 hours, giving patients little control over their blood sugar. In 1996, this formula was then modified to act in the short term, lasting only three hours. During the following years, other short-acting formulas received FDA approval and have remained largely unchanged since the 1990s.

Banting, Collip, and Best would no doubt roll over in their graves if they knew the current practices of America’s prescription drug companies. Today, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk sell a vial of insulin at 5,000% more than the less-than-$10 production cost. To put this figure in perspective, imagine paying $300 for a coffee that costs $6 to produce.

My most recent insulin prescription, three 10 mL vials of NovoLog, or about one month’s supply, retails for $1,001.99.

Amidst a national healthcare cost crisis, insulin lies at the epicenter of all prescription drug tragedies. Today, one in four Type 1 diabetics rations their insulin, setting themselves up for serious complications later in life. For Josh Wilkerson, rationing medical supplies was fatal.

The story of Josh’s early life as a diabetic is strikingly similar to mine. Diagnosed at eight years old in Pennsylvania, as a child Josh enjoyed the best state-of-the-art diabetic supplies, cost-free. Lucky for us PA diabetics, all children diagnosed with T1D, regardless of income level, automatically qualify for Medicaid, which covers any co-payments. But in 2018, when Josh turned 26 and was removed from his parents’ insurance, he struggled to keep up with the cost of his medical supplies. He turned in his state-of-the-art supplies for cheaper options, swapping out his insulin pump for syringes, and his high-quality brand insulin for $25 Walmart insulin. I had the chance to learn about the quality of this Walmart insulin from Dr. Kaisa Lipska, a practicing endocrinologist and Yale Professor of Medicine who led the study which discovered the now ubiquitous one-in-four statistic. “[Walmart insulin] is less of a good option for people with T1D,” she said, “but in an emergency, if someone’s running out of insulin, it’s better than nothing.”

In combination with his fiancé Rose, who also has T1D, their medical supplies were costing more than their rent. This downward spiral continued until the day Rose came home to find Josh collapsed in the shower. His most recent blood sugar reading was 400. At the hospital, doctors were able to revive him, but his body was in diabetic ketoacidosis. After a CT scan, doctors confirmed that he had gone through too much brain damage, and his family chose to remove life-support. He was 27 years old.

The thought that one of my friends might meet the same fate haunts me. During our conversation, Allie and I reflected upon the established “one-in-four” statistic and the number of kids at our camp: “let’s say there are sixteen kids in our cabin, that means four of them are rationing their insulin.” Diabetic children who are fortunate enough to attend camp are probably not the ones at the greatest risk of rationing their insulin, but the alarming proportion stands.

Another camp friend of mine shared how “My hairdresser has Type 1. We gave him vials of insulin because he couldn’t afford it.” Like Josh, as diabetic children in Pennsylvania, none of us have had to pay a cent for our insulin, but when we turn 18, and lose our secondary Medicaid insurance, and eventually turn 26 and get kicked off of our parents’ plans, we are on our own. In fact, my endocrinologist has specifically instructed my family to stockpile my 100%-paid-for insulin while we still have the chance.

“I had a conversation with my parents about that,” said Allie. She asked them “when I’m not under your insurance, what’s gonna happen to me?” The problem goes past insulin, with our insulin pumps and continuous blood glucose monitors (CGM), the price of medical supplies other than insulin is greater than insulin itself. “The fact that I’m going to have to pay for my own insulin when I’m out of college, my own sites, my own [CGM], is terrifying.”

Allie talked about her plans to go to nursing school and expressed concern knowing that she doesn’t plan to be making a large amount of money as a young adult. Towards the end of our conversation, Allie’s mother overheard us talking and added her perspective, sharing that she is especially concerned about “losing the secondary insurance. I always tell Allie I don’t want you to stress about that because Dad and I are here and we will help you out. I may be living on cereal and milk but I will always make sure you have what you need.” We shouldn’t have to endure this stress, and we shouldn’t have to feel like our lives are burdensome to our families.

But stress, for the sake of ourselves, our friends, and all Type 1 diabetics, we do. As Allie said, “you can’t ration your insulin, that’s literally rationing your life.”

A variety of factors have created a perfect storm of insulin price gouging, starting with America’s healthcare system. In places like the United Kingdom, with single-payer healthcare, the government is able to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies to lower the price of prescription drugs. The government can simply say “we won’t pay more than x amount of money,” and then the drug company can choose to lower its price, or lose out on that country’s drug market.

In the United States, however, drug companies have more power. Government purchasers could, in theory, negotiate with drug companies to get a lower price, but if the drug company doesn’t like the deal, they can go to any number of private healthcare providers. Because only three companies, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi — the “big three” — hold 90% of the world insulin market, essentially a monopoly, they have even more power to set their prices. But this alone does not explain why a vial of insulin that costs between $3.69 and $6.16 to make can be sold for $300.

The single biggest factor adding to insulin’s price tag is the lack of a generic version. For over-the-counter drugs, for example, Advil, one can switch to buying store brand ibuprofen and save a few dollars. For insulin, there is no such option. When I go to the drug store to fill my insulin prescription, there isn’t any option significantly cheaper than Novo Nordisk’s expensive NovoLog.

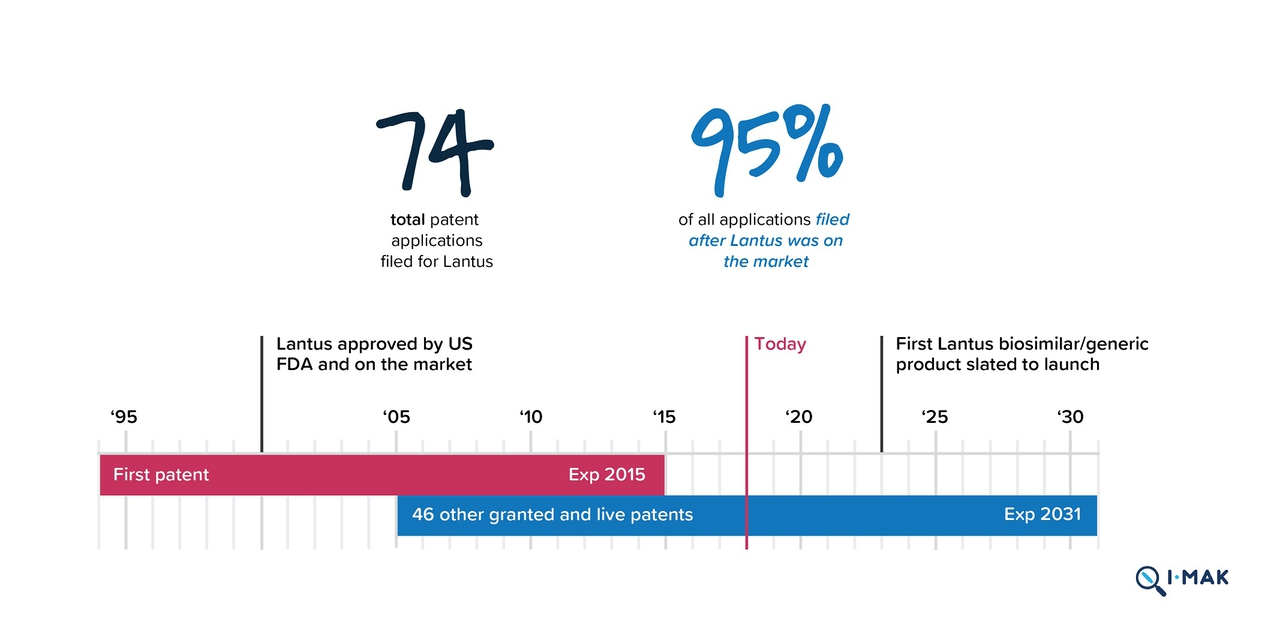

The system of patenting, for one, makes it difficult for generic insulin to reach the market. According to Rob Carroll, a Lawyer at Goodwin’s Intellectual Property Litigation group involved in patent litigation, “patents are issued for novel, useful inventions,” granting a monopoly to an inventor for a limited time period, and are “supposed to give the right amount of incentivization for novel inventions without giving people a perpetual monopoly.” Most patents last about 20 years, but some of the big three’s insulins created in the early 90s are still under patent, preventing the development of a generic version.

Sanofi’s insulin, Lantus, for example, got its patent in 1994, which should have expired in 2015. But after bombarding the United States Patent and Trademark Office with 74 patent applications after it received its initial patent, Sanofi gained patent protection until 2031. With each new patent application, Sanofi claims that it has improved the formula for Lantus, making it worthy of another patent. Consumer groups and diabetics using insulin say that the Lantus from 2000 is the same as the Lantus today. The practice of renewing patents for prescription drugs and keeping generics off the market, called evergreening, is common among the pharmaceutical industry.

Unlike Sanofi’s Lantus, other insulins, such as Eli Lilly’s, are now off-patent, meaning that companies willing to produce a generic version of insulin finally have their chance. Why haven’t they taken it? Unlike ibuprofen, which is a small-molecule drug, the process of producing insulin, a large molecule drug, is far more complicated. “It is not the sort of thing where you can cook up an exact replica in your lab,” said Carroll.

“The notoriously slow process of FDA approval also poses a barrier. The FDA is very busy,” Carroll pointed out. “When you have an agency that is overwhelmed the people who are biggest probably are best situated to provide a lot of information quickly and are nimble in responding to the agency,” putting smaller generic companies at a disadvantage.

Dealing with the long-term production timeline and FDA approval process takes time and money, but potential investors don’t have the economic incentive to support the production of a generic insulin.

Most states have automatic substitution laws that cover small-molecule generics. So when a drug that is bioequivalent to a brand version hits the market, it will automatically be substituted when a doctor prescribes the brand drug, thus lessening the co-payment for patients. Simply stated, small molecule drugs automatically have market share. Large molecule drugs are different, in that generic versions are biosimilar, not bioequivalent, so automatic substitution laws do not come into play. Instead, as Carroll explained, “A biosimilar company has to spend resources educating doctors and saying ‘no you should give us a shot because we are gonna sell at a lower price point,’” so “it’s hard for these biosimilars to get market share.”

The big three companies with deep pockets can easily pour money into marketing their drugs to physicians, but it’s hard for potential up-and-coming generic companies to compete. Penn Medicine’s endocrinology department denied my request for an interview, but I managed to speak with an anonymous Philadelphia-area endocrinologist about the interaction between physicians and pharmaceutical companies.

To give doctors the opportunity to learn about their drug, “pharma reps come in periodically with samples [of insulin],” according to the anonymous endocrinologist. Physicians give these samples, handed out like free kung pao chicken in a mall food court, to desperate patients in a short-term pricing emergency, to “try and help them as much as possible.”

Dr. Lipska also commented on pharmaceutical companies’ drug marketing. “The familiarity of the brand among clinicians is something that those companies have been building for years. It’s a Lilly product. It’s a Novo Nordisk product. You know what that is,” she said. “In order for the [biosimilar] companies to enter the market and be competitive, they will have to build that trust — that brand recognition.” This process takes time and money that small companies can’t afford.

With more barriers in place and less reward, the generic insulin business is not that attractive to potential investors.

Some generic versions of insulin do exist, but most of them have been produced by the big three and are only 15%-30% cheaper than brand insulin. Even Insulin Lispro, Eli Lilly’s own low-cost insulin, which is 50% cheaper than its insulin Humalog, still costs $137 dollars per vial. More promising than these “generic” insulins from the big three, Mylan and Biocon announced in June of 2020, that its generic insulin, Semglee, received FDA approval. This is a great step in the right direction. We will see just how great a step when the company releases its full launch plan and pricing details by the end of 2020, but we can still expect a pretty long wait before this drug hits the market.

Still, there’s more to the story. Some of Novo Nordisk’s insulins have been off-patent since 2013. Has it really taken six years for a company other than the big three to get FDA approval? Companies have been trying to launch generic insulin ever since the first versions went off-patent, but they run into barriers far before they send their plans to the FDA. The big three know that if a generic version hits the market, they will lose profits, so they have turned to “pay for delay” deals, where they pay a company to stop trying to bring a generic insulin to the market.

Back in 2016, for example, Merck planned to produce a biosimilar version of Sanofi’s Lantus. That is, until Sanofi sued Merck multiple times, claiming that Merck was infringing on Sanofi’s patent for Lantus. In response, Merck released this statement:

“We are confident that the [new drug application] does not infringe any valid claim of the asserted patents for Lantus. Merck respects and fully complies with US and international intellectual property laws.”

In 2018, Merck ended its research and development for the drug, citing concerns over the cost of production, “presumably due to payments from Sanofi to stay away,” according to consumer group Type1International. Even if these sort of pay-for-delay deals don’t work out, an expensive and time-consuming lawsuit never fails to slow down a company’s drug development.

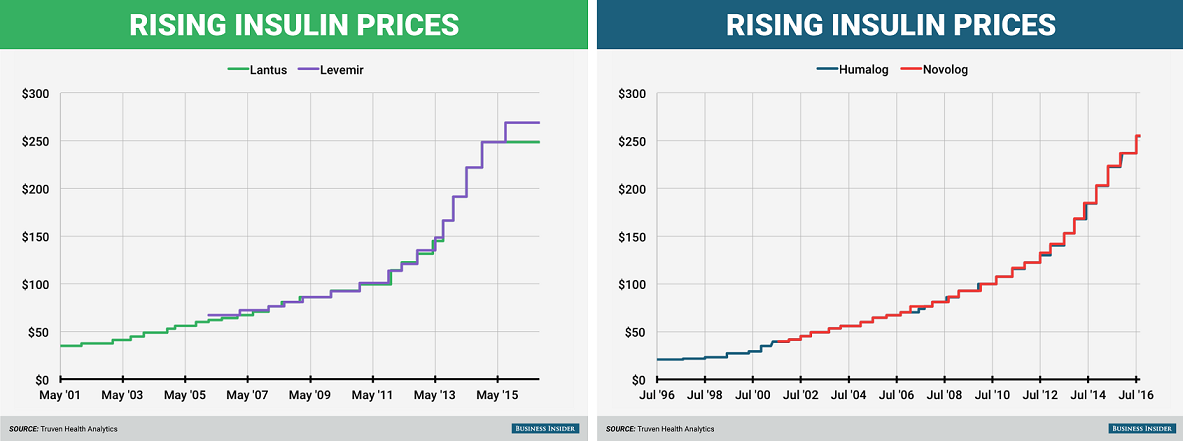

The big three have gotten into legal trouble not just with their competitors; over the past decade, they have faced multiple accusations of price-fixing. In our free-market economy, competition among the big three should drive the price of insulin down. Interestingly, their prices have gone up. In 2001, Sanofi’s Lantus cost $34.81 for a 10 mL vial, and, in 2006, Novo Nordisk’s rival product, Levemir, appeared at $66.96. In 2016, one year after Lantus’ original patent would have expired, both drugs’ prices skyrocketed to $248 and $269, respectively.

These graphs from Business Insider paint an incriminating picture: these companies raise their prices in a dance, taking a step forward together at each yearly musical interval. The prices of Humalog and NovoLog, from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk, have risen so consistently that the lines are indistinguishable.

Although this shadow pricing habit led to lawsuits from consumer groups in 2017 and a hearing in the House Energy and Commerce subcommittee in April of 2019, the big three have continued their price-fixing waltz. They claim that they have simply “monitored the market closely,” and that their high prices are essential to fund research and development of new lifesaving drugs. This system alone creates a vicious conflict of interest — the companies funding drug innovation and cure research depend on profits from people with the disease. When Eli Lilly says in its promotional videos that its “search for a cure never stops,” its shareholders truly hope the search will never end.

Follow the lawsuits, and one can find a slew of controversy over biosimilar versions of insulin; follow the money, and the story gets worse. In addition to their “research and development,” the big three spend millions on lobbying. In 2018 our senator, Bob Casey, was the number one recipient of donations from pharmaceutical companies in the U.S. Senate.

Looking through political donation websites, it’s hard to find a politician who isn’t in bed with Big Pharma. Even Bernie Sanders, the man who traveled to Canada with diabetics to buy insulin, received a million dollars from pharmaceutical companies in 2020 (almost double the second-place recipient, Elizabeth Warren, who is closely followed by Mitch McConnell). Later, during his most recent presidential campaign, Sanders pledged to reject any pharma money and said he would return any donations that violated that pledge. This didn’t stop Kamala Harris, Pete Buttigieg, and Joe Biden from each taking half a million dollars in pharma donations.

Even worse, Trump’s pick for secretary of Health and Human Services, Alex Azar, was previously the president of Eli Lilly’s United States division. During his time with the company, Azar oversaw raising the price of insulin from $74 to $269 between 2007 and 2017. Similarly, Joe Biden’s campaign chairman, Steve Richetti, was previously a lobbyist for Sanofi and Eli Lilly.

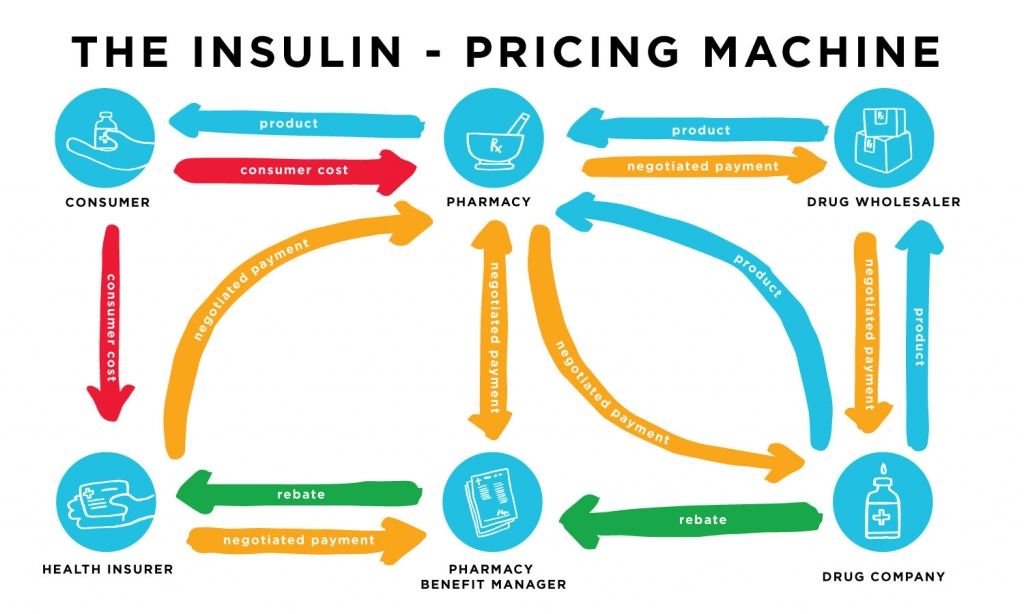

Though they are profiting, the big three companies are not pocketing all the money from rising insulin prices.

In 2017, Medicare shelled out $4.184 billion for Sanofi’s Lantus, but in the same year, Sanofi only reported $2.813 billion in sales for the drug. Where did the extra roughly $1.5 billion go? Between insurance companies’ spending and Sanofi’s profits, Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), the middlemen, are profiting from and contributing to insulin price hikes.

PBMs negotiate prices of drugs with the manufacturers on behalf of the insurance companies, supposedly to lower premiums for patients by getting better deals from manufacturers. Most often, they do this by encouraging insurance companies to choose generic instead of brand drugs, but in the case of insulin, choosing a generic drug isn’t an option. In theory, they still should be able to drive a hard bargain and lower prices for insurance companies, and eventually the patients. PBMs, however, aren’t subject to any regulations, allowing them to avoid transparency.

The PBMs are not required to disclose the discounts they receive from drug companies. With this lack of transparency, they are free to work in whatever way will give them the biggest slice of the pie. Often, drug companies like Sanofi have to pay a PBM to be able to sell enough product volume to insurance companies. In recent years, PBMs have become more closely tied with insurance companies, the troll under the bridge to which drug companies must pay a gold coin if they want to sell their product to insurance companies.

According to Duane Schulthess, a consultant working in healthcare regulations, “it is also possible to imagine a scenario in which PBMs play the drug companies off one another, offering the largest insulin sales volume to those providing the biggest margins in the PBMs’ direction.” Last July, President Trump signed an executive order addressing the PBM’s lack of transparency, though it only applies to senior citizens, and could potentially do more harm than good by raising patients’ insurance premiums by as much as 25%, as reported by SAT News.

Finally, to add to the long list of reasons why the price of insulin is so high, the big three fund the very organizations that are supposed to be fighting for diabetics. In 2015, Eli Lilly gave $15 million of its “research and development money” to “patient advocacy groups,” $3 million of which went to the American Diabetes Association (ADA). As a part of its website, the ADA has a “stand up for affordable insulin” page. Aside from its optical petition, inspiring “TAKE ACTION!” button, and policy recommendations it’s hard to find any concrete legal action the ADA has taken “to improve the lives of all people affected by Diabetes,” in accordance with its mission statement. This is not the case for other individual diabetics and consumer groups who do not take pharma money.

Diabetics in America are trapped in a web of systemic problems keeping them from their insulin: for-profit healthcare, the patent system, evergreening, complex FDA regulations, pay-for-delay deals, price-fixing, lobbying, political conflicts of interest, marketing schemes, and payment for interest each act as strands in the web keeping diabetics from healthy living.

Desperate times call for desperate measures, and Type 1 diabetics have gotten creative. As of 2018, there were over 10,000 GoFundMe campaigns related to insulin, people asking strangers for money so that they can live. Others have taken to TikTok, saying “please like this video, I’m a Type 1 diabetic who lives in America. Insulin is expensive.”

Less social-media-savvy diabetics have taken insulin production into their own hands, at-home brewery style. In 2015, a team of self-identified biohackers came together to produce a DIY cookbook for insulin, so that it’s easier for small start-up companies to get started on insulin production. “Our team is developing the first open-source organisms for insulin production that will be practical for small-scale, locally-based groups to use,” says their website.

Anthony Di Franco, the founder of the Open Insulin Foundation, says that “The usual sources on insulin have failed many people with diabetes and left them to die. […] We are taking over the stewardship of the medicine our lives depend on.”

There isn’t any regulatory process for non-commercially produced insulin, so who knows? If they ever publish this step-by-step guide to making insulin, I may have to invest in some lab equipment and take over a corner of my family’s kitchen.

Until then, other diabetics have looked to Canada for cheaper insulin. Bringing T1D to the center of media attention, last year Bernie Sanders took a bus trip to Canada to buy insulin with a group of diabetics, mounting his case against American corporate greed.

The trip, which included more reporters than diabetics, offered a valuable insight into the world of the insulin-price crisis for non-diabetics. A mother, speaking through tears at the Canadian pharmacy, reflected upon how “$1,000 got me six months of insulin for my son… That’s still less than what I pay a month in the United States.” Another traveler shared how the same insulin costing her $340 in America was a mere $30 in Canada.

“You are likely talking about corruption and price-fixing. You’re talking about collusion,” said Sanders as reported by the New York Times. “The time is long overdue for the American people, for the Congress, to say, ‘Enough is enough. We’re tired of being ripped off by a very, very greedy and corrupt industry.”

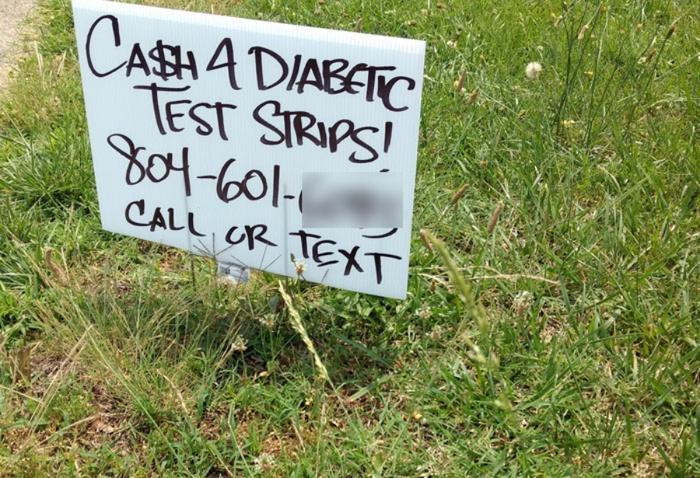

Other diabetics, who don’t have the option of traveling to Canada, turn to the diabetic black market. In early 2019, researchers from the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology surveyed 159 people who had traded medical supplies online. In these online communities, people seek help, and people give their extra medical supplies, just like my friend from camp, often not for any personal gain. They understand what less-fortunate fellow diabetics have to deal with. For legal reasons, I have never ever donated any of my extra, 100% paid for, and easily acquired diabetic supplies to a fellow less-fortunate diabetic.

This practice of trading prescription drugs is illegal, though the researchers did not receive any reports of complications related to the diabetes black market. Though most of these communities appear on Facebook or Reddit, some like Cr3 Diabetes, are legitimate nonprofits working to give medical supplies to those in need.

Uninsured diabetics who want to avoid illegally trading supplies can always go to the big three company’s plans to make diabetes supplies more affordable. So, posing as an uninsured diabetic, I paid a visit to Novo Nordisk’s website, which offered me four options for cheaper insulin. They are, of course, “working hard to keep our medicines available and affordable for people like you who rely on them. If you need help paying for your insulin or other diabetes medicines, we can help.”

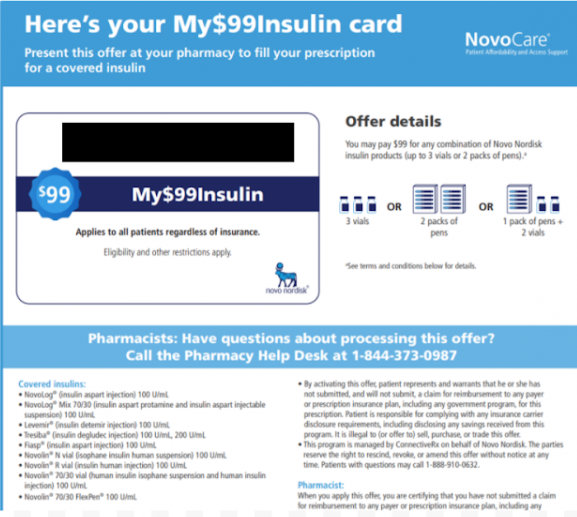

- Luckily for me, if I don’t have Medicaid or any type of insurance, I am eligible for a My$99insulincard, with which I can buy three vials of insulin, about one-month’s supply, for just $99. Posing as an uninsured diabetic, I received an electronic version of this card fairly easily. Great! But wait, I need a lot more than just the insulin to live as a diabetic. For one, I need syringes, which cost between $15 and $20 for a box of 100, of which I might use between 5-10 a day — not bad. But hold, on, I also need to know what my blood sugar is, so I need a meter, also about $20. To actually use this test kit though, I need a bunch of single-use test strips, which cost $20 for a pack of 50, and I might use 10 a day, if I’m skimping. In total, using the cheaper end of each estimate, I would pay $261.5 a month as an uninsured diabetic living as cheaply as I could. If I was a full-time minimum wage worker in Pennsylvania making $1,160 a month, this is one-fourth of my pay.

“My$99Insulin” card from Novo Nordisk that I was able to easily get by filling out their questionnaire as if I were an uninsured Diabetic. The ID number is blacked out to prevent illegitimate use of this card. - As a Pennsylvanian diabetic working for minimum wage, a $99 dollar plan just isn’t going to cut it. But remember, Novo Nordisk is here to help. I can also apply for its Patient Assistance Program, and I may be able to get insulin cost-free. All I have to do is download and fill out the application, gather proof of my income, take the application and proof of income to my health care provider, and wait 10 days for processing. During this time, any number of eligibility requirements might prevent me from qualifying for this program. Even if I do qualify, after 10 days without insulin, maybe my application will be processed by the time of my funeral.

- It’s a good thing that the Novo Nordisk website has a third option for me. Below its $99 dollar plan, and its Patient Assistance Program, it asks the question “Still don’t see an affordable option?” Since I still can’t afford the cost of the former, and I can’t afford the time and complex application process of the latter, this must be the option for me, so I eagerly click on “see how we can help.” The last option is a one-time offer for a free immediate supply of three vials of insulin, again, about one month’s worth.

My “Immediate Supply Card” from Novo Nordisk, worth three vials of insulin. I was able to easily get the card by filling out their questionnaire as if I were an uninsured Diabetic. The ID number is blacked out to prevent illegitimate use of this card. - After I finish my one month’s free supply I can look into Novo Nordisk’s partnerships to provide low-cost $25 human insulin, and “With your doctor’s guidance, human insulin can be a safe, effective, and affordable option.” Many diabetics, like Josh Wilkerson, who did his best to survive using human insulin, would have to disagree. Novo Nordisk didn’t respond to my request for an interview.

Michael Block, a Type 1 diabetic and the leader of Pennsylvania’s Type 1 International chapter, commented on Novo Nordisk’s programs in an interview: “It’s all just a bandaid, the main goal of the pharmaceutical companies is to not lower the list price so they are doing everything they can to avoid lowering the list price. It’s a go-to PR move.”

These programs, according to Block, aren’t helping any uninsured diabetics. “It’s terrifying,” he said, “when you turn 26 if you don’t have a job with insurance you’re screwed.”

Other diabetics, such as Myranda Pierce, a graduate student at Boston University School of Medicine, as reported by SAT News, agree that the big three companies’ efforts to improve access to insulin are inadequate: “I shouldn’t have to go beg for my insulin. It should be affordable to me.”

Why should you, most likely someone who doesn’t have diabetes, care about the insulin affordability crisis? Well, you’re paying. If you or your family pays taxes, through Medicaid, you are paying for part of my roughly $30,000 worth of annual medical supplies, along with all other Type 1 diabetics in Pennsylvania younger than 18. From 2012-2016, U.S. taxpayers bought more than $22 billion worth of Lantus through Medicare and Medicaid. But the government doesn’t have to keep transferring your tax dollars to the shareholders of the big three insulin companies. If Congress passed legislation reining in the monopolistic practices of the big three, American tax dollars could be better spent elsewhere.

If the government took action to make insulin and other diabetes supplies more widely available, America would also save an enormous amount of money by preventing diabetic complications. As of 2017, hospital visits from diabetes-related complications accounted for 30% of the total medical costs related to diabetes. Every time a diabetic rations their insulin, they are setting themselves up for an emergency room visit, costing American taxpayers more money. If we invested in accessible diabetic care, the costs from these hospital visits would dramatically decrease.

The need to lower drug prices has more recently become a bi-partisan agenda item. Though insulin isn’t so cheap that “it’s like water,” as Trump claimed in the first presidential debate of 2020, he did take action to lower drug prices. Last July, in addition to addressing PBMs, Trump signed two other executive orders addressing prescription drug pricing. But these orders, according to healthcare experts, are worded too vaguely to hold any real legal power.

More notably, on November 20th, the White House officially announced the Most Favored Nation rule (MFN), which it had been floating for months. Through the Department of Health and Human Services, the MFN rule will give Medicare Part B more negotiating power to lower drug prices to the amount that other industrialized nations, like Canada, pay.

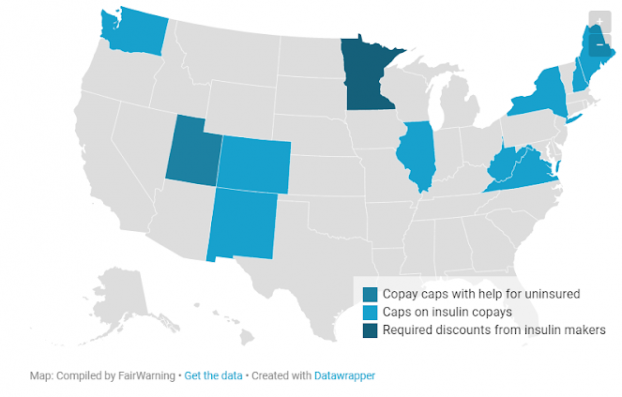

In addition to executive orders, Nancy Pelosi, Amy Klobuchar, and other legislators introduce numerous bills to lower the price of insulin in every session. These bills typically propose a combination of capping copays, banning PBMs and insurance company rebate schemes, allowing Medicare to negotiate for lower prices with drug companies, and putting limits on drug companies’ price hikes. Each of these measures from the White House and Congress, however, only have the potential to impact certain groups of diabetics.

According to Dr. Lipska, “None of these proposals cover everybody. I still see people struggling to pay for insulin every day in my clinic. We have more work to do.”

“I’ve come to the conclusion that you can’t really plug all the holes and solve this issue by focusing on specific groups of people,” she said, “It really does have to come down to lowering the actual price of insulin.”

Type 1 International (T1I), one of the many consumer groups advocating for diabetics, agrees. According to Michael Block, his ultimate goal is a federal price cap on insulin.“You wouldn’t have to worry about insurance companies,” said Block, “it would just be a law saying you can only charge x amount for insulin.”

Block first became involved in Type 1 International in college, when he began to notice insulin price increases. Diabetes “impacts a lot of decisions in your life when you’re constantly focusing everything around if I have enough money to stay alive for this month,” he shared.

Because Type 1 International, since its inception, has vowed to never take a penny of Big Pharma money, it faces an uphill battle. “One of the scariest things about this fight is that the pharma lobby is bigger than the gun lobby in terms of influence. They are influencing every single state legislator that they can give money to.”

So far, the organization has found the most success focusing on legislation limiting copay caps for insured diabetics. Last January, for instance, the Pennsylvania legislature introduced a bill that would cap monthly copayments for insulin at $100, though, after Covid-19 hit, it fell too far down the priority list to make it to the floor.

Copay caps, like most proposed legislation addressing the insulin pricing crisis, offer a bandaid solution; they only affect patients already under private insurance. And with lower copays, patients’ premiums and deductibles increase, canceling out any potential savings. Copay caps pressure insurance companies to lower the price of insulin, ignoring the root of the problem: insulin’s high list price set by the big three companies. Eli Lilly itself has supported copay caps, for example in Virginia, essentially passing on the responsibility of the insulin affordability crisis to the insurance companies.

Why do legislators avoid regulating the list price of insulin? It’s hard to go after Big Pharma when they are surrounded by an army of lobbyists. As reported by NBC News, Oregon state Rep. Sheri Schouten said that if the pharmaceutical industry is “going to come after you,” like they would if any legislature tried to implement a list price cap, “nothing’s going to happen.” So instead, the legislators target the insurance companies with copay caps.

As Dr. Lipska said, “for us to ensure access for everyone the actual price needs to come down.”

Of course, a federal price cap isn’t a popular option among anti-regulation politicians. To these critics, Journalist Merill Goozner offers a solution: unifying America’s fragmented insurance system with a national drug purchasing pool. A singular, unified, government-run purchaser of insulin would have enough negotiating power to buy insulin at a cheaper price. Goozner estimates that this pool could save American taxpayers $7 billion annually while also eliminating all copays and deductibles for insulin.

This option lands somewhere between a completely single-payer healthcare system, and our current private insurance system. California is already looking into a similar drug purchasing pool system.

As Goozner said, this pool’s negotiating power would at long last force the big three companies to “compete” instead of “collude.” For an idea that some might label as leaning towards socialism, it sounds pretty capitalist to me.

Four years ago, at summer camp, when I met the Novo Nordisk representative, I didn’t understand any of the complexities of Big Pharma. I took my insulin gladly and without asking questions. And, of course, I can’t blame this one man for Novo Nordisk’s exploitative practices.

With all the legal jargon, nuances of our healthcare system, and politicization, it’s easy to forget why America needs to protect all diabetics from insulin price gouging. I think of the diabetic people I know — Allie, Julia, Pat, Isabella, Grace, Hannah, Eric, Corrine, Makenna, Gabe, Sage — and the thousands of other diabetics in America currently rationing their insulin. As Allie said, “You have to put yourself in our shoes. Take anything that you need. Food. It’s a necessity to live and if you can’t get it you starve and you die. It’s the same thing with us and insulin.”

Diabetics in America are dying while the top pharma executives and shareholders sleep on a pile of blood money. Our government treats diabetics like having our insulin, having our lives, is a privilege. Insulin — the difference between life and death — must be treated as a right.