When representation isn’t enough

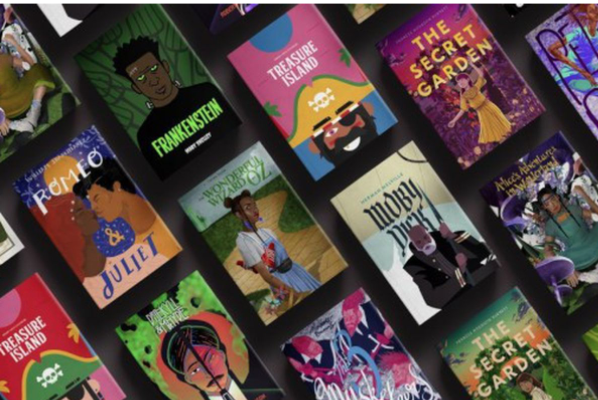

Covers of books in Barnes and Noble’s Diverse Editions, starring reworks of classical works where the lead characters are non-white, proposed in February 2020. Diverse Editions was criticized for Blackface and simply repurposing classical works written by white authors rather than featuring works by authors of color, and was ultimately not published.

November 11, 2021

Since the racial justice protests of last year, many believe that representation has taken a great leap forward. After all, a movie and a TV show featuring stellar minority representation were released this year. The Hollywood Diversity Report announced significant increases in minority film representation over the past decade, including women and people of color becoming more represented in film positions. Many activists are cheering over this increased minority representation. But is it enough?

Last year, people called on the US to deeply reflect on its racism. Racial justice advocates stressed the need for various action steps: implementing policies, calling out bigoted statements, supporting movements for racial justice, and educating oneself and others. Educating yourself reveals a lot about the racism situation in the US; for centuries, racism showed itself in all kinds of laws and practices, like slavery, segregation, redlining, stereotyping, and more.

Racism also prevented people of color from effectively pursuing better lives because they were denied opportunities to advance socioeconomically. As a result, as the US developed, top institutions became white dominated. People of color rarely make it to high level positions like science, entertainment, business, and more, leading to them believing that they could never make it to such positions. After all, we all look up to people in those institutions, hoping one day we could become one among them.

Therefore, racial justice advocates call for increased representation in the media, in higher education, in healthcare, and any position that’s predominantly white. Representation, according to activists, means having your own identity present on “the big screen.” It fosters a sense of inclusiveness among marginalized groups and increases diversity in a homogenous environment, letting people of color express themselves as who they truly are, not some stereotype.

There already seems to be progress. Black Panther’s release in 2018 provided Black Americans a crucial way to express themselves and their culture authentically, untampered by any stereotypes. Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, released this year, had a similar meaning for Asian Americans, telling a tale fitting to Asian traditions. In politics, the 2021 elections delivered major wins for candidates of color into mayoral or governor positions. And the election of Kamala Harris as vice president of the US allowed women and people of color to literally see their identities in the White House.

But will representation alone bring us to racial justice? Obviously not. In order for racism to truly end, representation must be accompanied by policies and practices that undo racism as well. So far, anti-racist practices enacted are less than satisfactory. Some states and institutions are even walking backwards in anti-racism. Diversity alone is not enough.

Police brutality is still rampant, with police killing over eight hundred people this year, still disproportionately Black. Qualified immunity still exists to prevent police from being held accountable by granting them effective immunity to lawsuits. A police reform bill in Congress, proposed last year, has not been touched on for months. President Biden’s promises to address racism have still come up empty so far.

School curricula are still lacking in diversity. History classes often teach racism as if it were all in the past, rarely linking it to racism in the present day. Literature classes often assign books written by white male authors, and health classes teach health tailored to a white, cis, straight setting while scantily considering that of people of color and LGBTQ+ people. Despite this, several states are restricting discussions of racism, with some even lifting the requirement that schools teach about the Civil Rights Movement and white supremacy altogether.

Anti-Asian hate still proliferates despite the existence of Shang-Chi and Squid Game, with slurs and physical attacks making the news every now and then. Over nine thousand cases are reported, and there could be thousands more unreported cases. Biased coverage of Asian countries continues to make this problem worse.

So what can we do to address racism and other forms of discrimination? There are plenty of things to do. As individuals, you can start by calling racist remarks out. If you do not feel comfortable doing that in front of your friends, you could pull them aside for a while and “call-in”; in other words, explain to them privately why the remark was harmful. You can donate to organizations that advocate in some way to address racism. Or you can join them!

As activists, let’s keep advocating for increased representation, but do not stop there. Our activism must also include the other facets of racism emphasized just as vigorously as lack of representation. Whether it is police brutality, hate crimes, or the whitewashed school curriculum, these facets of racism are just as hurtful, if not more, than lack of representation. After all, lack of representation is not why a quarter of Asian Americans feel fearful over anti-Asian hate crimes, or why many Black Americans are suspicious of police violence.

For police brutality, ending qualified immunity and having officers foot the court bill are a start. Defunding the police and reinvesting in communities are not bad solutions. To address increasing hate, start by describing the pandemic correctly and minding the media coverage. For the curriculum, advocate expanding the current content to include the history of other peoples in the world without whitewashing while maintaining the high-level credit.

Even in regards to representation, it falls short. In the same Hollywood Diversity Report mentioned earlier, minorities are still underrepresented in the film writer, director, and executive producer roles, making up only a quarter of directors but 40% of the population. Women only make up 20% of director positions while making up half the total population.

Representation also runs the risk of tokenism. It is all too common to hear that a movie with diverse actors is released only to find out that those actors only take on perfunctory or heavily stereotyped roles, or that a workplace or school brags about its diversity only for the minorities to have far less opportunities to participate or feel excluded.

Representation cannot stop the other forms of racism and can only give an illusion that racism is finally addressed. Representation fosters a sense of inclusiveness among marginalized groups, increases diversity in a homogenous environment and creates a platform for people of color, but that’s it. Even the ten legendary rings in Shang-Chi can only do so much to combat racism.

Thus, we must address racism in all its other forms in order to truly reach an anti-racist society. Simply advocating for more representation is inadequate. After all, we’ve come so far, but we still have a long way to go.