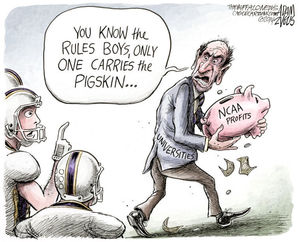

Forty hour practice weeks. Billions of dollars in generated revenue. Zero pay. Welcome to the world of college sports, where student athletes bring in big bucks for their schools and receive no cash compensation in return. The National Collegiate Athletic Association contends that the amateur status of college athletes justifies limiting payments to education-related costs. But as the college athletics industry rakes in nearly $11 billion in annual revenue, the athletes are lobbying for a piece of the pie. Whether college athletes should be paid or not has been a bone of contention for decades. And just recently, the focus of a federal court ruling.

On September 30th, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld a finding that NCAA’s amateurism rules capping payments to athletes violate antitrust laws. NCAA regulations, it claimed, unfairly restrain competition for top athletes. At the same time, the court ruled to allow the NCAA to restrict colleges from paying their athletes anything beyond the cost of attendance. The three-judge panel struck down a plan for universities to provide athletes with up to $5,000 a year of additional cash payments—for name, image and likeness rights—after they leave school.

Currently, an athletic scholarship in a Division I school can cover up to the full cost of attendance. This includes not only tuition, room and board, fees, and books, but also incidental college costs like traveling to and from home, as well as personal expenses like cell phone bills. But for many athletes, the current allowance is grossly inequitable.

College sports is a business, no matter how you look at it. Take the nearly $1 billion in TV revenue that the NCAA earns from March Madness. The average price of a 30-second ad in 2014’s championship game was just shy of $1.5 million, while use of the NCAA logo cost corporate partners between $10-$35 million. Next consider the salaries of coaches like Alabama’s Nick Saban, who brought home a whopping $7 million paycheck in 2014. Then there’s the alumni donations that pour into a university after a big win, as well as the massive revenue generated from ticket and merchandise sales. While everyone else in the business seems to be benefitting from windfall profits, it would follow that the athletes—the ones who make it all possible by sacrificing their sweat and blood—deserve a portion of the money they bring in. But, that’s simply not the case. And pay for play advocates proclaim that these athletes are being fully exploited by the NCAA’s restrictive no-pay rules.

Just ask Kelsey Lally, a Division 1 rower for Boston College. “I think that college athletes should be compensated,” says the Radnor Class of 2015 graduate. “I understand how regular students would be frustrated by the benefits of the athletes, but athletes do a lot for the school that isn’t fully appreciated. Athletes put aside mandatory hours of athletic work, not including the “optional” workouts on their own. D1 athletes represent the school, and in some ways, market the school around the world. By seeing Boston College football on ESPN, kids might grow up hoping to go there. Being an athlete takes a lot of time and effort, and I fully support compensation because I believe [it is] well deserved.”

While the NCAA seems to operate in a wholly capitalistic atmosphere, it continues to endorse the concept of amateurism in college athletics. These diametric values naturally lead college athletes like Kelsey to question the status quo of the present system. Most of them want their fair share of the pie that they feel they deserve; which comes with no surprise, since a vast majority of them will not go on to play professional sports or even graduate with a diploma. Many colleges witness abysmally low graduation rates for their student athletes. Due to the high-stakes nature of games, athletes are spending more time training than on their academics. According to the Summer 2014 issue of Harvard Law bulletin, only 45 percent of men’s basketball recruits at Syracuse graduate. While at UConn, that number drops to a shocking eight percent. What’s more, a one-year renewable scholarship contract can be terminated by a coach or school at any time, for any reason. Say an athlete gets injured, can’t maintain necessary grades, or breaks an NCAA rule by accepting a free meal from an alumni, he can kiss his scholarship goodbye; and with it, any chance for a professional career. Considering the sacrifices of economic opportunity that student athletes make for the benefit of a university, supporters of pay for play cite the blatant inadequacy of what they receive in return.

On the other hand, college athletes are amateurs, and anything that amounts to payment for playing would professionalize them and completely transform collegiate sports. Critics of pay for play argue that the system would undermine the dignity of competition and turn college athletics into a sordid business. If college sports fell into a market system where each athlete negotiated his or her own salary, Pandora’s Box would crack wide open with bidding wars, subjective measures of worth, and corrupt professional agents.

Opponents further argue that the cost of attendance model should not be undervalued. Apart from the admissions advantages that athletes receive, they benefit from the complete university experience—concerts, lecture series, fitness facilities, clubs, etc.—at no cost to them. They also have free access to sports medicine care, nutrition and strength conditioning specialists, and some of the top coaches in the sport. Not to mention high profile name recognition, media exposure, and a dedicated fan base.

What seems short-sighted to opponents of pay for play is the notion that compensating a college athlete can solve all or even some of that student’s long-tem issues. Critics remind us that student athletes are not university employees. They’re students first, and athletes second. Paying student athletes undermines a college’s fundamental purpose of higher education—something that can’t be priced, but something far more valuable than an annual stipend. Where a college education was once viewed as a priceless commodity, the growing trend points to the belief that it’s simply an opportunity to make money. To many pay for play critics, keeping the amateur status of student athletes is essential to honoring and preserving the value of an education.

In the end, amidst skepticism that all vested parties—the NCAA, student athletes, and universities—can arrive at an agreement, one thing remains certain: as the pay for play debate continues to unfold out in the public as well as the legal system, determining fair ways to divide up the revenues is only going to get more complex.

Categories:

Pay for Play?

October 25, 2015

0

More to Discover