International Conflict Hitting Close to Home: A Radnor Perspective on US-Iran Relations

March 2, 2020

While keeping up with international politics on the news from the Philadelphia suburbs, the magnitude of the events playing out oceans away can seem hard to grasp. But Radnor is not as far removed as one might think. Community members, such as Iranian-born Foreign Language Teacher, Madame Daryoush, are personally involved and affected by international conflicts. Speaking with me Madame shared her story, and described her perspective and concerns moving forward as an Iranian-born American observing her country of origin’s unstable state from overseas.

American-Iranian relations, in particular, over the past month have been tense at best. Since May of 2018, when President Donald Trump backed out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), commonly known as the Iran Nuclear Deal, tensions between the United States and Iran have been escalating. On January 3rd of this year, Qassim Soleimani, Iran’s leading general, was assassinated by the United States.

With the original quid pro quo deal, Iran agreed to stop progress towards nuclear power, in return for economic benefits. Though the other nations who signed on to the deal, including the UK, Russia, Germany, China, and France, tried to keep it alive, without the support of the US, most of the agreement collapsed. During the months after Trump backed out of the deal, the US re-imposed sanctions on Iran, provoking an economic crisis.

Further escalating tensions, in June of 2019, two oil tankers, owned by Norway and Singapore, were attacked, and the U.S. Navy rushed to evacuate 44 sailors from the two vessels. The US pointed fingers to Iran as the cause of the attack, who denied any involvement. A week later, a US military surveillance drone was shot down by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, though the US took no retaliatory action.

In response to the economic sanctions from the US, in July, Iranian officials declared that they would not limit the number of centrifuges used to purify uranium in their nuclear facilities ﹘ in essence, meaning that they would not limit fuel production for nuclear weaponry. The JCPOA was structured on the premise that, if the deal failed, Iran would acquire a nuclear bomb in no less than one year. In the worst case, today, though estimates vary, if Iran prioritizes the advancement of their nuclear weapons, they will be five months away from becoming a nuclear-weapon state.

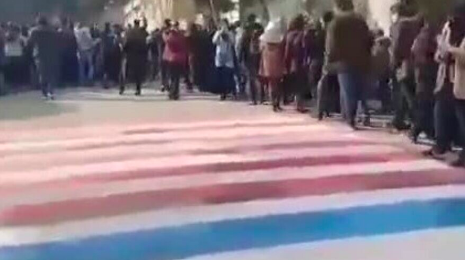

In the months leading up to the assassination of General Soleimani, tensions remained high. On September 14, Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen carried out a drone strike on Saudi-Arabia oil facilities, temporarily blocking half the oil supply of the world’s largest producer. Also, mass protests erupted in Iran surrounding oil prices, escalating to the point that the internet was shut down for several days in Iran — Amnesty International estimated that 300 people were killed in protests.

Prompting the most recent acts of aggression, on December 27th, an Iranian backed militia group, Kataeb Hezbollah, fired a rocket into a U.S. Military Base in Iraq, killing a US contractor, in this case, a linguist, and wounding several other troops. Three days later, in retaliation, the United States bombed Kataeb Hezbollah bases in Iraq and Syria, killing 25 fighters. Iraq’s parliament, seeing the bombings in their territory as a violation of its sovereignty, voted to expel all approximately 5,200 US troops from Iraq. The Prime-Minister, however, did not approve of the ruling, and Iraq has taken no action to remove US troops from its territory.

In response to the bombing of Kataeb Hezbollah bases, hundreds of Iran-backed militia held violent protests outside the American Embassy in Baghdad, though there were no casualties. The US decided to respond to the protests outside the embassy and the ever-rising acts of aggression with drastic action: killing the Iranian General Qassim Soleimani just outside of the Baghdad Airport.

The president’s unexpected and extreme action, comparable to if Iran killed the US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, sparked both domestic and international outrage. Democrats in Congress and US international allies opposed their exclusion from the decision making process, and Iran declared that “a forceful revenge awaits” those who caused the death of the general. After five days of mourning for the general, whose funeral gathered over one million Iranian attendees, 50 of which were killed by being trampled by the crowds, Iran retaliated by sending twelve missiles at two US military bases in Iraq, killing no one. Later, it was revealed that Iran informed Iraq of the planned attack, which in turn warned the United States so that all military personnel could be safely secured before the attack was carried out. Though the Iranian press told its citizens that at least 80 US troops were killed, the action was seen as de-escalatory, as Iran was able to maintain its pride in the eyes of its citizens, without killing any US troops and taking further steps towards war.

Just as conflict seemed to be subsiding, a Ukrainian commercial flight was shot down just after takeoff from Tehran, killing all 176 passengers aboard, on January 8, 2020. Originally Iran blamed mechanical malfunction for the crash but later admitted that it was shot down due to human error, confusing the commercial flight with an attack by the US. Iranian President Hassan Roahani offered his “sincerest condolences” in a tweet, and Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif said, also in a tweet, that the human error was “caused by US adventurism.”

As it stands, though the Iranian-US relationship remains hostile, war with Iran seems to have been avoided. Though with the JCPOA no longer in place, the situation will continue to be unstable at best. For all Iranians, in their home country and overseas, the recent protests and violence spark fear of an uncertain future. As Madame Daryoush shared, “[the conflict] breaks my heart. It is tough to accept that idea because it creates sad memories.”

During our conversation, Madame spoke fondly of her childhood. Born into a highly educated family in Iran around 1960, she grew up bilingual, attending a French school in Tehran. Because of her father’s job as a diplomat under the Shah, they moved to Brussels, Belgium when she was a young teenager, three years before the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Speaking both Persian and French throughout her childhood, it seems from a young age Madame was destined to be a language teacher. During the Revolution, for their safety, her family sought political asylum in Belgium. As Madame detailed, “I had all my education in Belgium, I became Belgian, until I fell in love with an American-born Iranian and I decided to move to the United States. That is why I am here now.” It wasn’t until thirty-two years later that Madame returned to Iran, to fight for the recuperation of her family’s land, which had been by the Islamic Government of Iran after the revolution.

Though she currently lives half a world away, Madame has remained deeply observant and conscious of the current political climate and international relations of Iran. Above all, she expressed frustration with the “poisonous bi-partisanship” and “polarization of the political scene.” In response to the current conflict and specifically the assassination of Qassim Soleimani, she holds mixed feelings. On one level, as she brought up, the general was by any standards morally corrupt. Madame considered the “worst thing he had done to his own people was killing a lot of students in Iran, back in November.” She also acknowledged, however, that the general “was a heroic figure for a lot of people in Iran” and, by her standards, killing him violated international law.

More generally, Madame Daryoush expressed concern with the level of American intervention as a whole. “Any intervention, as history has shown many times, is not giving a good result. Ultimately the whole momentum should be built through the people of Iran.” Many Iranians, as she explained, are somewhat counterintuitively supportive of Donald Trump, because he initially took steps to minimize America’s involvement with Iranian affairs by backing out of the JCPOA. Other Iranians argue that the intervention could be beneficial by promoting the change of the regime but, as Madame asked, “at what price?”

Though Iran underwent a violent and drastic revolution less than half a century ago, much change remains to be desired. As Madame described, “Iranian people are not dumb, they are fed up with the regime” Though she is hopeful of political change, protests and upheaval don’t guarantee an improvement in Iranian citizens’ freedoms: “I have a lot of concerns because we don’t know who will pick up the power. It changes minute by minute. I do not have an answer.” Though she does not expect successful change within her lifetime, nor her childrens’ lifetimes, she hopes that Iran will follow the path to revolution on its own.

Throughout the telling of her story, Madame continuously mentioned the importance of education: “no wonder I am a teacher because this is my only safe ground:enlightening, being patient, understanding, accepting.” She also recognized the danger posed by partisan reporting and propaganda. With so many sources of information available to us, she urged all members of the Radnor community to always discuss difficult topics, read and get informed from multiple sources, representing both sides of the story.

Madame described other Iranian immigrants as “contributing to the richness of this society with the power of speaking.” Through offering her insight and sharing her story to the Radnor community, she has certainly added wisdom, richness, and awareness to our lives.