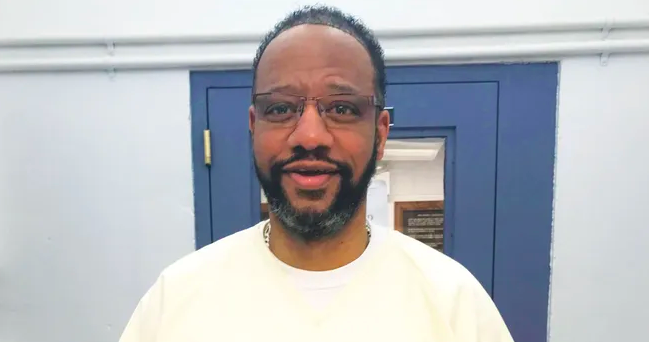

Pervis Payne: A Murky Fight for Justice

June 2, 2021

Pervis Payne was seen fleeing the Hiwassee Apartment complex on June 27, 1987, in Millington, Tennessee. According to officer C.E. Owen, Payne had appeared to be “sweating blood,” and after a brief interaction between the two, Payne threw his bag at the officer and ran. Payne was found at the home of a former girlfriend later that day, telling the officers he didn’t kill anyone.

Within the Hiwassee Apartments Charisse Christopher, a neighbor of Payne’s girlfriend, along with her two children, had been brutally stabbed. Although her three-year-old son lived, Charisse and her one-year-old daughter, Lacie Jo, had tragically died.

Beyond this, Payne and the arresting officers have created separate narratives detailing what happened between Payne’s arrival and departure from the apartment complex.

The prosecution has supplied a narrative in which Pervis Payne had been injecting cocaine into his veins, drinking malt beer and looking at a pornographic magazine, while being driven to his girlfriend’s apartment. When entering the apartment complex, he approached Charisse Christopher and began to make sexual advances towards her. Once denied, Payne carried out the forlorn crime.

The yells of an argument had been heard throughout the complex, but only Charisse could be understood. While the complete interaction between the assailant and Christopher has not been deciphered, a sun-bathing neighbor saw a forearm wearing a gold watch lean against an open window. Although the time at which this interaction occurred is unknown, the watch had been worn by Pervis at the time of this scene.

Other commotions were heard, none of which could be intelligibly described. And after the altercation between Payne and Officer Owen, he was found in the basement of a former girlfriend. Among a group of friends, he was not wearing a shirt, shoes nor socks and was profusely sweating. His pupils were dilated and had been foaming at the mouth. Once handcuffed, Payne insisted he “didn’t kill no woman.”

Payne repeatedly told the officers he was just the “complainant,” but the segments found at the apartment were quite incriminating. Payne’s DNA was found on Charisse, her children, on the phone in her apartment, on a beer can which the prosecutors claim he left, on the walls of her apartment, on the syringes and other beer cans found in the bag thrown at officer Owen. Among the beer cans which were found left in the apartment, a hat with Payne’s hair had been looped around the arm of Lacie Jo.

While Pervis’s alibi could exempt him from the incriminating DNA evidence, the items which he left have yet to be substantially explained by the defendant. While interviewed, many of his attorneys have suggested that his cap and the DNA evidence were planted, and many on social media have preached that there is no authentic proof against Payne, neither statement can be carried beyond speculation.

Among the DNA evidence, the arresting officer also found a piece of cloth with cocaine residue in his pocket. But despite all of the evidence obtained by the officers—the syringes, the beer cans and cocaine residue—the police did not administer a drug test. Even when asked by Payne’s mother, Bernice, the officers still withheld.

While there are many points of argumentation from the defendant which have just been hearsay, the prosecution has consistently countered their narrative with evidence-based reasoning. But why promote this narrative which sees a drug-induced Payne attack this family if the police had not even given the defendant a drug test? Would it not further prove the narrative?

And although this glaring question did not sway the jury, a “smoking gun” which the prosecutors and many articles use to show Payne’s guilt is an oral testimony he took during a state-based cross-examination. He was asked how Christopher’s blood got on his left leg: “Evidently it probably came—had to come from when she—when she hit the wall. When she reached up and grabbed me…When she—when she hit—when she hit when I got ready to run up—when I got ready to vomit…When she—when she hit—when she hit when I got ready to run up—when I got ready to vomit.” The interviewer attempted to make Payne restate his answer more straightforwardly, but Payne then began to deny even saying blood got on his leg after she hit the wall.

This directly contradicts the narrative which Payne has been sticking to since his arrest. Although this could be written off as just a mere misspeak, as he had been repeatedly stuttering and repeating himself throughout the interview, in every other interrogation and interview he had not mentioned Charisse hitting the wall once.

With all the evidence against Payne, his story still has amassed a growing following of people who believe Payne is innocent after only hearing his side. The discourse surrounding this case can oversimplify the narrative. The thought of a black man being wrongfully executed for such a heinous crime is horrific, especially in a time such as now. The District Attorney, Amy Weirich, has spoken out against the progressive social media users who have contacted her office after reading a couple headlines. She asserts that the narrative which the defendant has maintained pulls on heartstrings and is “manipulating” the members of the Black Lives Matter movement and followers of the Innocence Project who are claiming Payne’s execution to be “cruel and unusual,” despite the clear evidence supporting otherwise.

Although being granted clemency for the sake of appealing to the Black Lives Matter movement is an injustice to the Christopher family, Weirich’s frustration cannot be taken quite seriously given the prosecution’s and her own repeated use of victim impact statements. During Payne’s trial, Weirich repeatedly brought the victim’s family members to the stand and discussed what this act had done to those closest to the Christopher family. She focused on the stripped potential of the single mother, Charisse Christopher, and the tragic death of her one-year-old daughter. And on a subject of its own, repeatedly highlighted the injuries to the victim’s “white skin.” Nonetheless, these deaths are tragic, but the jurors are trying to determine Payne’s guilt, not reflect on the injustices done to Charisse and Lacie Jo. A segment from Weirich’s closing argument:

“No one will ever know about Lacie Jo because she never had the chance to grow up. Her life was taken from her at the age of [twelve months old]. So, no, there won’t be a high school principal to talk about Lacie Jo Christopher, and there won’t be anybody to take her to her high school prom. And there won’t be anybody there—there won’t be her mother there or Nicholas’ mother there to kiss him at night. His mother will never kiss him good night or pat him as he goes off to bed or hold him and sing him a lullaby.”

While the statements used by Weirich are moving, the absence of a mother figure has no real bearing on the blameworthiness of Payne. The repeated use had become a major issue within the trial, and although ultimately the prosecution was permitted to use these statements, a major portion of Payne’s sentencing drew away from Payne himself, focusing more on the victim impact statements. In the wake of Payne’s trial, further restrictions have been placed on the use of victim impact statements.

Apart from his cross-examination, Pervis Payne has maintained the narrative of waiting for his girlfriend outside her apartment, when the altercation between her and the assailant had broken out. And unlike the rest of the neighbors, claimed he ran past a dark figure while rushing to see the commotion, who he believes is the true perpetrator. After finding the source of the loud argument, Payne stumbled into “the worst thing [he] ever saw in [his] life.”

A wave of horror rushed through his psyche as he walked into one of the most awful crime scenes in Tennessee’s history. Payne attempted to comfort the struggling Charisse Christopher, who was still surprisingly breathing, despite the knife embedded in her neck. As he struggled to comprehend what lay before him, another wave of dread rushed through his mind as he began to think about where he was.

Around Pervis lay a dead one-year-old girl, a dying three-year-old boy and their mother in his arms, breathlessly grabbing at a kitchen knife sticking out of her neck. Amid this desolate apartment, Payne, a black man, bewilderingly sits around three white, lifeless bodies. Pervis is no stranger to the stereotypes and the racism within Millington, Tennessee. A town well-known for its lynching and the injustice that is Emmett Till’s death. Trying not to be yet another innocent black man falsely accused of a heinous crime, Payne fled the scene and subsequently ran into what he feared most. During the trial, Payne testified:

“As soon as I left out the door, I saw a police car, and some other feeling just went all over me and [I] just panicked, just like, ‘Oh, look at this. I’m coming out of here with blood on me and everything,’ It going to look like I done this crime…I saw a police getting out and…a white man at that. And that scared me even more, you know, like I didn’t have a chance, like I know he’s going to think I did this.”

Officer C.E. Owen, racist or not, saw Pervis practically “sweating blood,” distressingly running from the crime scene.

Pervis has maintained this story for over thirty years, despite the sex-crazed, drug-induced narrative the police have been insisting. And as character testimony has repeatedly shown Pervis’s kind heart, the prosecution claims he tried to solicit sex from someone he barely even knew. And when denied, he grabbed a knife and stabbed Charisse eighty-two times, her son, Nicholas, twenty-one times and Lacie Jo, her daughter, nine times. With each respective victim receiving a gruesome number of impalements, Payne’s attorneys have pointed out precedents and the recurring motive of an enraged ex-spouse. Given the grisly nature of this murder, would it not seem as though there had to have been a genuine motive? Charisse and her children had been butchered by some stranger, who, by many accounts, is a “kind and devoted person” (Bobbie Thomas, his girlfriend at the time). Unlike Christopher’s emotionally and physically abusive ex-husband who was in a minimum-security prison, Fort Pillow State Penitentiary during the event, but has still been a recurring alternate suspect the defense has provided. Although recent statements have shown that inmates commonly are permitted to leave the penitentiary during the day, without facing any repercussions.

While the DNA evidence can support the narrative of the prosecution, it can, likewise, support the defendant’s account. Payne has incessantly claimed he had only tried to comfort the Christopher family in their final minutes, but the fingerprints found on the handle of the kitchen knife have diminished this wrong-place, wrong-time narrative. Although the DNA samples found cannot objectively prove his immediate guilt or innocence, a report conducted by the Forensic Analytical Crime Lab of Hayward, California has recently given Payne’s narrative more credibility. During a brief, the crime lab found the DNA of a third-party. Although the third party could not be identified, due to the sample’s degraded quality, the report has been the light at the end of the tunnel for Payne and is the reason why his case, which came to a verdict thirty years ago, is now again in the news.

For the prosecution to have found Payne’s and Christopher’s DNA on the knife, would they not have also found this third-party’s prints all those years ago? Weirich has a history of withholding evidence, and during a Harvard Law School study, Weirich was ranked highest of all prosecutors in Tennessee for misconduct. Right now, the true perpetrator could be walking free, unscathed, for thirty years, because Weirich was determined to convict Pervis. Letting the evidence deteriorate for over thirty years and securing the safety of the true perpetrator.

During Payne’s hearing in July of 2020, Weirich confirmed she had the aforementioned DNA evidence, and although it seems like a small feat to obtain evidence which one is legally obligated to present, the court was lucky to review the DNA samples. As there had been fingernail scrapings, also mentioned during the hearing, which was to be later reviewed with the recent DNA report. Yet shortly before the evidence was to be presented in court, it had inexplicably disappeared.

The Innocence Project has claimed time and time again the scrapings identify the true perpetrator of the crime but were unable to present it. And although the defendant would have much rather reviewed the possibly exonerating evidence, they have been nonetheless pleased with the eyebrows raised in the wake of this supposed disappearance.

In light of this new evidence, Weirich has continually attempted to deny this DNA evidence revision. “[N]othing in the DNA testing exonerates Pervis Payne. The evidence of Payne’s guilt was and still is overwhelming. The jurors declared so with their verdict in 1988. Countless appellate courts have said it since.” said Weirich. But many have spoken out against this potential barring of evidence. Robert Hutton, a death penalty expert, states, “If you are about to put somebody to death, why wouldn’t you want to get every bit of evidence that you could get.”

Along with the Innocence Project, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has assisted Payne during his trial and time in prison. Although NAACP has been pressing for the review of the DNA evidence, they have also pointed at the stereotypical motive for which the prosecution has provided for Payne. Similar to the motive during the case of Emmett Till, many have drawn parallels. Till was a young boy who was lynched for allegedly whistling at a white woman. During his trial, an all-white jury proved the men who lynched Till not guilty. After being acquitted, the men confessed to the crime in an interview with Look magazine and the woman who accused the boy of whistling, Carolyn Bryant, recanted her story, saying no sexual advances had ever been made towards her by Till.

And like the unsuspecting Till, ample character analysis has shown Payne’s lack of violent behavior or criminal activity at all. Bobbie Thomas, his girlfriend, during her testimony stated he “behaved just like a father that loved his kids.” Payne met Thomas and her children while working at his father’s church after divorcing an abusive ex-husband, Payne comforted the family during a dark point in their lives.

Payne’s mother and father both testified speaking on Pervis’ lack of any criminal record prior to this event. The three both pointed out that Pervis had no previous drug use nor drank alcohol, despite the drug-induced narrative and the DNA evidence the prosecution has provided.

While the NAACP and other organizations have been pursuing evidence-based reasoning for Payne’s exoneration, many in the NAACP and attorneys from the Innocence Project have contradicted their narrative. During an interview, Venessa Potkins, the lead attorney of the Innocence Project, stated that much of the evidence on Pervis had been fabricated and he had not been drinking at all. But during a podcast with Kelley Henry, another lawyer from the Innocence Project, revealed that Pervis “may had been drinking a little.”

The Innocence Project’s articles on the case have formatted their content in a way that only shows the damning evidence which they have collected, but none of the evidence which the prosecution has likewise supplied. While this is not illegal and an obvious tactic if one is trying to persuade a reader to their side, it often leads to people talking about the overt innocence of a soon-to-be-executed man. As said by Weirich:

If the facts aren’t on your side, attack the investigation. Mr. Payne has been vigorously defended by teams of lawyers for more than 30 years. The case has been reviewed by the Shelby County Criminal Court, by the U.S. Supreme Court and by every state and federal court in between. The proof of his guilt is overwhelming. As with nearly every death penalty case, this is a last-ditch defense effort to use press releases and social media to shift public sympathy to the convicted offender and away from the only victims in the case – a young mother and her young children who were stabbed more than 100 times.

While there is incontrovertible evidence supporting Payne’s innocence, there is still undeniable evidence supporting his guilt. In a case that is very much my-word-against-yours, credibility is key. Statements such as “The police tampered with evidence at the crime scene. They moved the victims’ bodies,” (Kelley Henry) which when read out of context seems tragic but has not been verified by any piece of evidence anywhere. By contradicting narratives and making false statements attempting to paint Pervis as an innocent man may sway the unresearched, but not those in a court of law.

Nonetheless, an unrelated piece of argumentation which the Innocence Project has been relentlessly pursuing is Payne’s intelligence, or rather lack thereof. Seventy-five being the benchmark for intellectual disability, Payne received a seventy-eight on his IQ test. Dr. Huston, a criminal psychologist, stated during testimony that Payne was “mentally handicapped.” Given precedents and the “evolving standards of decency” in the Eighth Amendment, the Innocence Project is claiming that Payne, guilty or not, cannot be executed under the rights of the constitution.

Citing Atkins v. Virginia, where the defendant was convicted, but during the sentencing phase, had been taken off death row due to his “mental retardation.” During the time of Payne’s initial sentencing, his handicap was not recognized, nor even known, and as such, he suffered as a witness for himself, as shown when he stated: “Evidently it probably came—had to come from when she—when she hit the wall.” When interviewed by the Innocence Project, his mother explained that “[g]rowing up [Pervis] struggled in school and, despite his best efforts, was not able to graduate. His teachers [said] he put in a lot of effort, but had difficulty learning to read, spell, and do math…He is not able to follow complicated instructions, including driving to new places.” The defendant claims being intellectually disabled makes one more prone to arrest and, given Deryl Atkins removal from death row, it is unconstitutional to kill Pervis Payne.

In light of the report conducted by the Forensic Analytical Crime Lab of Hayward, California, Governor Lee reprieved Payne’s execution until April 9. Currently, his fate is being decided by the Tennessee Supreme Court.

If Payne is executed, there will be an outcry for yet another black man killed by the state, despite all evidence proving his innocence. If Payne is acquitted, there will be those still wondering why his cap was found looped around Lacie Jo’s arm.

As of now, Payne remains in his cell on death row, receiving formulaic letters from followers who Payne nevertheless appreciates, awaiting his verdict and fighting against a prosecutor who practically lives by the mantra: “guilty until proven innocent.” Alone, comforted only by the coarse walls of his cement cell and the few visits he is permitted to see what is left of his family—knowing what has been so obvious to him, but such a mystery to everyone else.