In Whose Honor?

January 29, 2016

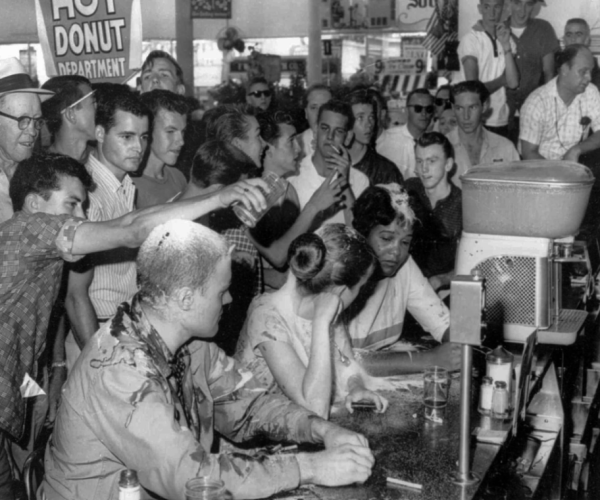

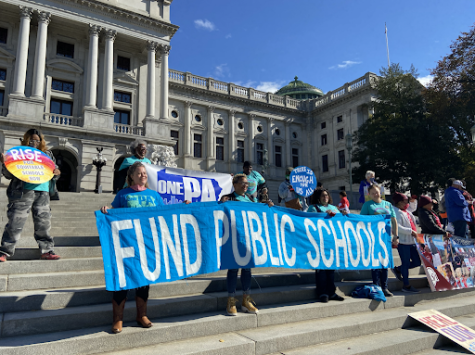

The propriety of using Native American names and images as sports mascots has been a topic of public controversy in the United States and Canada since the 1960s, as part of the movement for Native American civil rights. There have been protests and other actions targeting the more visible professional teams such as the Cleveland Indians and the Washington Redskins, as well as college and high school teams. A movement to expunge these symbols as mascots has swept across the nation. All but three universities have eliminated their Native American names and symbols as have several hundred high schools. The topic has been discussed at local high schools including Neshaminy (PA), Red Clay (DE), and Radnor.

Those in favor of using Native American titles and symbols for sports teams argue it is a way of honoring their cultures and commending them for their strength and fierceness in battle. Others contend that sport traditions are important to uphold, even in the face of community opposition. Opponents of using these nicknames and symbols claim that they are racially derogatory and make stereotypes of complex and divergent cultures. They claim that using such “slurs” are an offensive and tasteless way to honor Native Americans.

Adidas has recently offered to help schools change their Native American mascots by providing free design resources and financial support to address any potential costs. The athletic-shoe and apparel maker announced this initiative at the White House Tribal Nations Conference on November 5th. Eric Liedtke, Adidas head of global brands who traveledtravelled to the conference, said sports must be inclusive to everyone. “Our intention is to break barriers to change –change that can lead to a more respectful and inclusive environment for all American athletes,” he said.

Adidas emphasized that the initiative would only include high schools, and that the company would not mandate that schools change their mascots and nicknames. In response to this program, President Obama expressed his approval, calling the effort “a smart, creative approach, which is to say, all right, if we can’t get states to pass laws to prohibit these mascots, then how can we incentivize schools to think differently?” He even took it a step farther, admitting how he hopes Adidas will extend their offer to professional teams.

One group, however, was not as thrilled as the Ppresident with Adidas’s proposition. The Washington Redskins quickly jumped to defend themselves. “The hypocrisy of changing names at the high school level of play and continuing to profit off of professional like-named teams is absurd,” team spokesman Maury Lane said in a statement. “Adidas makes hundreds of millions of dollars selling uniforms to teams like the Chicago Blackhawks and the Golden State Warriors, while profiting off sales of fan apparel for the Cleveland Indians, Florida State Seminoles, Atlanta Braves and many other like-named teams.”

“High school social identities are central to the lives of young athletes, so it’s important to create a climate that feels open to everyone who wants to compete,” Mark King, president of Adidas Group North America, retorted in a statement. “But the issue is much bigger. These social identities affect the whole student body and, really, entire communities. In many cities across our nation, the high school and its sports teams take center stage in the community and the mascot and team names become an everyday rallying cry.”

Many Radnor citizens probably haven’t heard of the Radnor Raider controversy. Objections have been raised about pairing Native American symbols with the term “raiders,”, implying that these cultures are rooted in warlike practices. Dr. Sally Scholz, a philosophy and ethics professor at Villanova University, contends that symbols like the tomahawk are often stereotyped as tools of war when they were mostly used for hunting, cooking, and ceremony, and have no place in our public schools.

Despite these objections, Radnor High School principal Dan Bechtold says “there are currently no movements within Radnor to alter the mascot/nickname in any way, and there will be no changes “unless directed by the Radnor Township School Board. We are currently not exploring the option of moving away from the Raider name or logo.” Bechtold insisted that “there are many community members, alumni, and current students who are proud to call themselves Raiders.” Michael Petitti, Radnor Township School District Director of Communications, is currently investigating the history of Radnor’s “Native American-inspired nicknames, mascots and logos.” Concurrently, Mr. Petitti encourages “all efforts, both from the private and public sectors, to examine and eradicate depictions of any group of people if these depictions are found to be racially derogatory.”

A similar controversy is unfolding in the Red Clay School District (DE), where there is a strong community effort to eliminate one high school’s use of the “Redskins” nickname. A high school Spanish teacher in Red Clay, Ms. Ana Viscarra-Gikas, is involved in this effort. “Some images are sacred or religious and to use such images and symbols is wrong. Native American cultures should be studied, understood, and valued,” she said. “Their sacred symbols should not be used or displayed for sports competitions; it is devaluing entire cultures/civilizations for sports.” She noted that many people in the community are resistant to changing sports mascots. At a recent community meeting in Red Clay to discuss this issue, Chief William Daisy of the Nanticoke Tribe (Delaware), told the group that Native Americans should not be used as mascots, and that the headdress does not represent him or his tribe. These headdresses are typically reserved for Chiefs of the western plains tribes, not eastern woodlands tribes.

At Radnor High School, one anonymous student believes the objections to Native American mascots is hypocritical. “Why is there so much unrest over the use of Native American imagery in sports,” this person said. “We’ve got teams like the Fighting Irish of Notre Dame [and] I don’t hear anyone making a fuss over that mascot! If the people supporting this movement want to see some change then they can’t just leave certain minorities out of the equation. It’s gotta be all or nothing.”

Dr. Scholz maintains that these ethnic groups are completely different. “Irish Americans were not the victims of genocide by European colonists. They were not systematically slaughtered or forced to live on reservations,” she said. “It seems disingenuous to claim we are honoring people who were treated this way. Even using seemingly innocent symbols like the ‘Fighting Irish’ encourages us to resort to stereotypes when talking about any subordinate group.”

This past month, the University of North Dakota changed its long-time nickname from “Fighting Sioux” to “Fighting Hawks.” Closer to home, the Pennsylvania Human Rights Commission recently ruled that Neshaminy’s use of “Redskins” is “racially derogatory [and creates] a hostile educational environment.” It remains unclear how these trends might influence the Radnor’s continued use of Native American names and images as sports mascots.